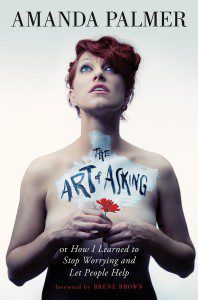

Musician and performance artist Amanda Palmer has a new book titled The Art of Asking, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help. If you like her music, if you like her blogging and tweeting, or if you want to learn more about her marriage to author Neil Gaiman, you’ll like the book. If you don’t, you won’t.

Musician and performance artist Amanda Palmer has a new book titled The Art of Asking, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help. If you like her music, if you like her blogging and tweeting, or if you want to learn more about her marriage to author Neil Gaiman, you’ll like the book. If you don’t, you won’t.

I enjoyed reading it, but that’s about as far as I’m going in reviewing The Art of Asking.

Why I read this book and why I’m writing about it is Amanda Palmer’s monster success with crowdfunding. In 2012 she set up a Kickstarter to finance her new album. She set a goal of $100,000 – she raised almost $1.2 million. That success led to a TED talk and now to this book. It also led to a backlash from people who didn’t understand the $1.2 million represented pre-sales, not donations, and from people who felt she was no longer allowed to ask for help from fans.

Many people are uneasy with the ethics of crowdfunding. What (and who) gets funded seems to have less to do with the merits of the project and more to do with how effectively the requestor can run a campaign. I see people trying to finance medical expenses who can’t raise more than a few hundred dollars, while a campaign to make potato salad raised $55,000. Crowdfunding is a great way to raise money for discretionary projects – it’s no substitute for a just and compassionate society.

People with money choose what to do with it and sometimes they use it to support artistic and religious endeavors. This is true for people with $3 in their pockets and for people with $3 billion in brokerage accounts. For those of us who are trying to fund our art, music, books, events, and institutions, our primary question is not whether we should use crowdfunding but how we can do it effectively.

The value in The Art of Asking comes from the stories of how Amanda Palmer funded her music. This is what I’ve distilled from them.

Make a connection. People will give to strangers because it makes them feel good about themselves. People will give to friends because they want to help. Sometimes all it takes to turn a stranger into a friend is some genuine eye contact, to let people know you see them. The catch, of course, is that lets them see you too – and most people are very good at spotting masks. Maybe they can’t see through your mask, but if they spot the mask and not your real face they’ll know the connection is contrived. Take a risk and make a genuine connection.

Make a fair exchange. Too many people think of exchange as a trip to Wal-Mart: buying some thing for some money at the lowest possible price. If we feel like we paid a low price, we think we’ve won. If we pay too much, we feel like we’ve lost.

Done right, exchange is not a game to be won or lost. Exchange is simply the Pagan virtue of reciprocity in action.

If you’re crowdfunding, you’re asking for money. What are you offering in return? A CD? A book? A smile? Private access? Vicarious participation?

Again, get out of the Wal-Mart mindset. I think The Wild Hunt is great and worth our support. I give them money, they give me a link on their site. That link generates zero revenue for me – in the Wal-Mart mindset it’s a bad deal. But I like seeing Under the Ancient Oaks listed on one of the most influential Pagan websites, so I’m happy to give them more than I would if I was simply dropping cash in a collection box. It’s a fair exchange.

Build a base first. For decades, nonprofits (including churches) have planned their funding on an 80-20 rule: 80% of the contributions come from 20% of the donors. If you want to make your budget, you’ve got to find, grow, and nurture high givers.

In crowdfunding that rule doesn’t apply. The crowdfunding sites say the most commonly selected package is at the $25 level. Amanda Palmer raised $1.2 million but she had 25,000 backers. That’s an average of about $45 each.

All the details of Amanda’s campaign are still on the Kickstarter website, meaning any geek with a spreadsheet and a few minutes (that would be me) can figure out the breakdown. Achieving 80% of her contributions required 72% of her backers, and as predicted almost 38% selected the $25 package.

Crowdfunding is many people giving a little, not a few people giving a lot.

As the crowdfunding detractors point out, the money mostly goes to those who are well-known and well-liked, not to those who are most deserving. Again, this is no substitute for a just and compassionate society, but it is a great way to raise funds for discretionary projects. If you want to raise money through crowdfunding, build and expand your base of friends, fans, and supporters first.

Do something people want to be a part of. Perhaps the most attractive exchange that can be made is to allow people to be part of a project. I can’t be a rock star, but I can be part of a rock star’s album. I can’t be a Pagan journalist, but I can be part of what many have called our “newspaper of record.” I can’t build an archive and research facility for the Pagan community, but I can be part of the New Alexandrian Library.

What are you doing that others want to join? What are you doing others wish they could do, but don’t have your talent or your skills or – let’s be honest – your dedication? If you’re doing something you can be proud of, chances are others would like to be a part of it too. How can you let them join you?

Tell your story. No amount of marketing flash can make up for a project that’s boring or an artist who can’t connect with other people. But even the best project needs a strong story: what it is, why it’s important, who’s behind it, how people can help, and what’s in it for them if they do.

The Pagan community had our own crowdfunding success earlier this year. Morpheus Ravenna asked for $7500 to finance the writing of The Book of the Great Queen – she ended up with almost $19,000. Her campaign website is still up – you can see the story of the book, the introductory video, and the tiers of backer rewards. Morpheus did an excellent job of telling her story and people responded.

The campaign was brilliant, but listen to Morpheus introduce herself in the video. She spent years becoming “a professional artist, a Celtic studies scholar, and a priest of the Morrigan.” Without all that work and all the people she connected with in the process, there would be no base from which to draw supporters.

Crowdfunding has become a seemingly magical source of money for a variety of projects and causes. But like all magic, it’s far more complicated than it appears on the surface.