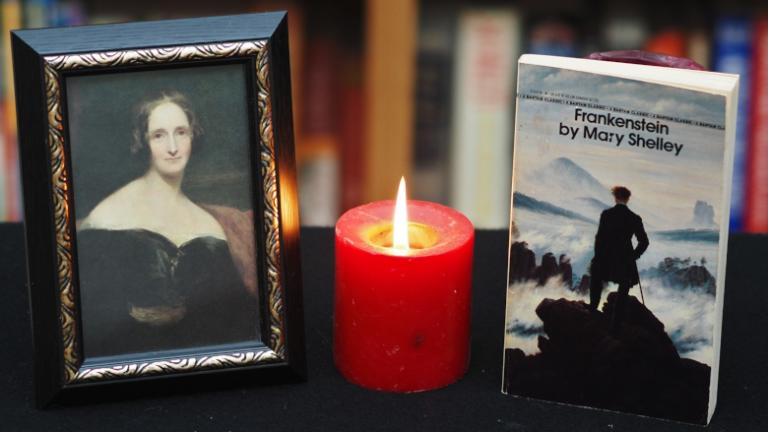

I just finished re-reading Mary Shelley’s classic 1818 novel Frankenstein. It’s a pioneering work of horror and science fiction, and it’s as relevant today as it was when she first wrote it.

Frankenstein and me

Regular readers know that my first loves in the realm of horror (some would say my obsession) are vampires. But Frankenstein has always been right there too.

The first movie I ever saw on Shock Theatre was Dracula (1931). The next week they showed Frankenstein (1931). A couple weeks later they showed Dracula’s Daughter (1936), followed the next week by Bride of Frankenstein (1935). There was Son of Dracula (1943) and Son of Frankenstein (1939). Hammer Films did the same thing. They started with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and followed it with Horror of Dracula (1958) – both starring Christopher Lee in the title role.

I like horror books and movies not because I want to be scared, but because I want to be fascinated: with castles and forests, cauldrons and books, magic and monsters.

As a nerdy little kid who struggled to fit in, I especially identified with the monsters. I wanted to be Dracula, but I felt like I was Frankenstein.

For all my often-voracious reading, this is only the second time I’ve read Frankenstein. I’m struggling to remember when I read it first. My best guess is sometime in the early 1990s. I know I read Dracula for the second time in 1992, in preparation for seeing Bram Stoker’s Dracula that November. I suspect I read Frankenstein about the same time.

I’m reading more fiction these days. It’s mostly contemporary horror and urban fantasy, but I’m trying to sprinkle in some classics. I re-read Dracula in late 2022 and Carmilla in late 2023 – it was time to tackle Frankenstein again.

And so I did.

Reading a 206 year old novel

The main thing I remembered about Frankenstein from 1992 (or whenever) was that it was difficult to read. The prose is formal and unfamiliar. It didn’t help that I was reading an old mass market paperback printed in 10 point font. I’m normally a fast reader – I had to cut my reading speed about in half.

As I understand was common for novels of the day, Frankenstein is written as a series of stories told from one character to another. It begins with a letter from a Captain Walton on board a sailing ship exploring the Arctic to his sister back in England. Early on he rescues Victor Frankenstein from the ice – then we hear Victor telling his story. When we eventually hear from the Creature’s point of view, we have him talking to Victor, who tells the sort to Walton, who tells it to his sister. It works, but as with the prose, the method is unfamiliar.

When I re-read Dracula (first published in 1897) most recently, I was struck by how Christian it is. I credited that to Britain being a thoroughly Christian culture at the time.

Frankenstein impressed me with how Christian it isn’t. Religion is hardly mentioned and when it is it’s often for negative reasons, such as the priest who harangues Justine into confessing to a murder she did not commit. For all its talk of life and death, there is no discussion of heaven or hell. And for all that Frankenstein is often described as a cautionary tale for man interfering with the affairs of God, the Christian God is almost never brought up.

Internet sources are in disagreement as to Mary Shelley’s religious thoughts and beliefs. She was intelligent and curious and she lived 53 years – it is likely they shifted over the course of her life. But Frankenstein makes it clear that at age 19, she had little desire for religion in general and for established religion in particular.

It’s alive!

Books and movies are two very different ways of telling a story. The challenge for scriptwriters is to adapt the book for the screen, being neither slavish to the original nor losing sight of the book’s main characters and themes.

Peggy Webling adapted Frankenstein into a stage play in 1927. John Balderson adapted Webling’s play further, screenwriters Francis Edward Faragoh and Garrett Fort turned it into a script, and director James Whale turned that into the brilliant 1931 movie.

The movie spends much of its time in Frankenstein’s laboratory. There is the body, the defective brain, the storm, the electricity, all culminating in Colin Clive’s Dr. Frankenstein shouting “it’s alive!”

The book is much more understated. Victor engages in his “unwholesome trade,” the Creature awakens, Victor is horrified at what he has done and runs away, and when he comes back the Creature is gone. The bulk of the story is not in the making, but in the consequences of the making.

Geneva: 1816

Many of you know that Frankenstein was conceived in a storytelling contest between Mary, her husband Percy, Lord Byron, his traveling companion Dr. John Polidori, and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont. They were living temporarily in Geneva – 1816 was the “year without a summer” caused by the volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia the previous year. The weather was cold and rainy and the party spent most of their time indoors.

This contest produced both Mary’s groundbreaking novel and Polidori’s The Vampyre, the first modern vampire story in English. Byron wrote a fragment of a vampire novel – it’s available in some anthologies (all five pages of it). Percy wrote “something about a ghost” that has been lost, and if Claire wrote anything there is no mention of it.

Byron and the Shelleys rented separate houses, but it was Byron’s house Villa Diodati where the storytelling took place, at least according to their accounts. Villa Diodati is still there. Unfortunately, it has been carved up into “luxury apartments” and is not open to the public.

I would pay an irresponsible amount of money to spend a long weekend in Villa Diodati, especially if I could persuade a few of my close Pagan and magical writer friends to join me. Alas, that’s not possible.

It’s just as well. I would be chasing someone else’s inspiration instead of following my own.

How to make a monster

Contrary to what some have said (likely in the more loose movie adaptations), Mary Shelley never named Frankenstein’s creation. He’s simply called “the Creature” or occasionally – by an angry Victor – “demon.” The idea that he was named Adam comes from this line:

I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

The Creature comes to life and is immediately abandoned by his creator. Everywhere he is shunned and attacked because of his appearance – an appearance his creator made. When others are helpful to him – even unknowingly – he repays kindness with kindness. And when Victor reneges on his promise to create a mate for the Creature, the Creature takes his revenge in kind.

In the eternal question of nature vs. nurture, Mary Shelley comes down strongly on the side of nurture.

None of the Creature’s murders are justified. He understands this, saying “you hate me, but your abhorrence cannot equal that with which I regard myself.” Revenge upon the innocent is never justified.

More relevant to our world here and now, revenge leads only to more revenge, which leads only to destruction and death.

This was portrayed brilliantly in Penny Dreadful (2014 – 2016). As in the novel, the Creature is abandoned by his creator, shunned by society, and becomes a murderer. But as he is befriended – especially by Vanessa – he becomes a friend. He takes the name John Clare after the English poet (1793 – 1864) and by the end of the series, he is perhaps the most human of all the characters.

Is this canonical? No. Is it plausible? Definitely.

Who is the monster?

A meme I see occasionally says:

Knowledge is knowing Frankenstein isn’t the monster.

Wisdom is knowing Frankenstein is the monster.

This is a dangerous oversimplification.

The Creature is not the villain of Frankenstein. And yet when he kills William, Henry, Elizabeth, and indirectly, Justine, he is a monster.

Victor is the villain of Frankenstein. But he started with the best of intentions. His fatal sin was not arrogance or blasphemy but cowardice: his refusal to accept and nurture his creation, and then his refusal to keep his word and create a mate for him (though, as both Bride of Frankenstein and Penny Dreadful showed, it might not have gone well if he had).

There are two monsters in this story, and two ways of becoming a monster.

Treat people monstrously and they will become monsters.

Treat people monstrously and you will become a monster yourself.

Frankenstein is out of copyright and is available for free on Project Gutenberg.

To answer the questions I know are coming, no, I have not seen Poor Things (2023) or Lisa Frankenstein (2024). I likely will see them eventually, though at this point the rental prices on Amazon Prime are more than I want to pay.