New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has a new book titled Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious. The obvious error of saying that “everyone” should be anything aside, it’s good, though not perfect. But it wasn’t written for me, and probably not for you either. And it has one unfortunate problem.

Once again my religious nerdiness has me reading a new book by a mainstream author released through an Evangelical publisher. Ross Douthat is a politically conservative New York Times columnist who is also a practicing Catholic. Would this be yet another reactionary piece of proselytization that subtly (or not-so-subtly) says that any religion that isn’t the author’s is dangerous and/or evil?

For the most part, no.

Believe skips the practical benefits of religion like friendship and community and instead makes an intuitive and experiential case for why being religious (in the commonly-understood meaning of the term) is a more reasonable approach to life than being non-religious. I find most of Douthat’s arguments persuasive.

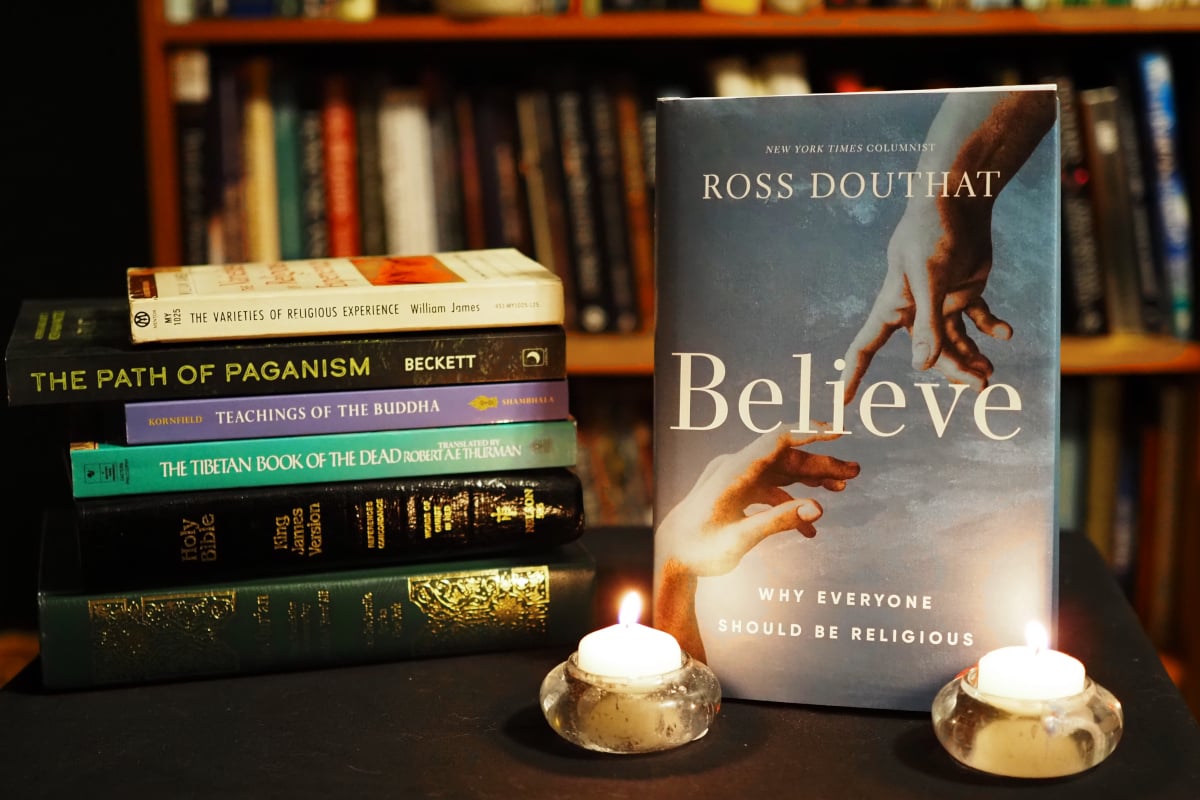

I should – I’ve made many of them myself, either here on the blog or in The Path of Paganism.

And that led me to wonder: since it’s not attempting “proofs” of Christian doctrine and it’s respectful of all religions (though it argues some are better – or at least, more likely – than others), who is this book for?

First, let’s look at the case Ross Douthat makes for why we should all believe.

The origin of the universe is likely unknowable

The first chapter “The Fashioned Universe” is the weakest link in his case. Douthat looks at the orderliness of the universe and concludes – like many before him including Aristotle, who was a Pagan – that there must be a Prime Mover. Perhaps there is, but there are other possibilities that are at least as likely. I wrote about this in 2023 in A Pagan Look at the Origins of the Universe. Perhaps God (in the sense Douthat understands God) and the universe are one and have always existed. Perhaps there is a Creator God, but they are so far outside the Universe that we can never hope to know them. Or perhaps the origin of the universe is not just beyond our knowledge, but beyond our ability to know.

More troubling, Douthat claims that the universe appears to be designed “for us” – that humans are special. Evolution shows that this isn’t the case, while animism tells us that all living beings have mind. It’s not that we’re no better than the animals, it’s that the other animals are conscious beings just like we are. And what of the intelligent life forms that almost certain populate at least a few other planets in this universe that is so large we struggle to imagine it?

Fortunately, Believe gets better after that.

We are more than the product of brain activity

“The Mind and the Cosmos” argues that the essence of who and what we are is more than the product of brain activity. I’m in total agreement.

Douthat says that “when intellectuals stopped taking mystical experiences seriously, actual human beings kept on having the experiences.” I’m to the point where it’s easier to accept that magic is real than to keep trying to rationalize it away, plus I’ve had numerous first-hand experiences of Gods and other spirits. And also, the Myth of Disenchantment is not a new thing.

He says that “becoming a religious seeker raises your odds of some kind of mystical experience or communion.” Again, that matches my own experience (both first and second hand), and it matches Dr. Dean Radin’s research. I found myself nodding in agreement with most of this section.

Commitment and tradition are good and necessary

“The Case for Commitment” argues that diligently following any positive religious path is likely to bring tangible results, and also likely to bring you closer to Ultimate Truth even if you can never be sure you understand what that is.

He makes “The Case for the Big Religions.” As a follower of a rather small religion, I’m uncomfortable with that, but I completely agree that the average person is more likely to find a helpful path and get closer to Ultimate Truth by following in the steps of those who’ve gone before us than by trying to start from a blank slate and figure it all out themselves.

When he points out that individual religious traditions (i.e. – Christian denominations and their functional equivalents in other religions) have different emphases on “the ethical, the experiential, and the liturgical” and that those different emphases will speak to different people, he’s absolutely correct. As I’ve mentioned before, I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I had grown up in a more liturgical church instead of the “preachin’ prayin’ singin’” of the independent fundamentalist Baptists.

I wanted to get angry with him for saying that “the popular forms of Paganism [are] fundamentally naïve about the kind of terrain they’re encouraging people to navigate.” But while I and many of my co-religionists who’ve been doing this work for years know exactly who and what we’re dealing with, I know a lot of Pagans and witches who don’t. So I can’t complain too much.

Three stumbling blocks

Douthat addresses three serious objections to orthodox religions and their claims. His treatment of the Problem of Evil isn’t bad. But the Problem of Evil simply isn’t an issue in polytheism, with its many Gods of limited power and scope. It’s a major concern in monotheism, and no one – including Douthat – has ever answered it satisfactorily.

His answer to why religious institutions do so many wicked things is adequate, but it overlooks the simplest explanation: because religious institutions are human institutions and even the best humans have the capacity for great evil.

His answer to “why are traditional religions so hung up on sex?” ignores the biological and social needs of the times when the traditional religions were founded – needs that are very different in our time of overflowing population and modern medicine. But he’s correct that sex is dangerous: it presents serious risks of unwanted pregnancy, disease, and heartbreak. The answer is education and consent, not abstinence, control, and forcing people into sex and gender roles that don’t fit them.

Who is Believe written for?

I struggled with this question from the first page: who is Douthat trying to convince?

It’s not atheists. His arguments aren’t likely to persuade the hardcore anti-theists, and in any case New Atheism is in decline. It’s not Christians who are leaving the Church because of hateful and exclusionary politics – the book really doesn’t address that problem. And while he argues that New Agers and other DIY religionists should pick something and dive into it deeply, most of them don’t have a problem with the basic supernatural premises of Believe.

On the day the book was launched, Douthat posted a Twitter thread that explained his approach:

I think now more than ever the Christian writer needs, if not a theory that justifies *all* the “different religious experiences” in the world, at least a theory that puts religion as a general phenomenon in some kind of coherent relationship to Christian faith.

And also

I think you’re just clearing away some impediments specific to our culture – both the sense that religious belief is irrational and the sense that a successful religious quest is impossible – so that people can make progress toward the Truth.

Douthat is trying to keep people who grew up without much formal religion from sliding from shallow belief and agnosticism into atheism. And he’s trying to “prepare the ground” for them to be receptive to more explicit Christian proselytization in the future.

And for all the respect he shows toward other religions and for as open as he is to people finding truth where ever it presents itself to them, in the final pages Douthat engages in the kind of explicit Christian proselytization he avoided through most of the book.

Choosing a path

The final chapter is titled “A Case Study: Why I Am a Christian.” Douthat tells his story of Episcopalian to Pentecostal to Roman Catholic. That’s not a common journey, but it’s not much of a stretch, either. Religiously, he stayed pretty close to home, as most people do.

At some point, those of us who take religion seriously have to set aside our comfort – or discomfort – with what we were taught, engage with the truth claims of the world’s various religions, examine the evidence, search our hearts and souls, and make a decision. I’ve done that. So have many of you.

Ross Douthat has done that too. He finds the evidence for the historicity of the Gospels to be convincing. I do not. He sees the success of Christianity in its early centuries as evidence of divine favor. I see it as fortunate timing, political support, and missionary zeal. So be it – we don’t have to agree to respect each other’s choices.

A subtle altar call is still an altar call

But while he is willing to trust that his God will not turn away those who did the best they could but ended up on another path, he is unwilling to do the same when it comes to his own soul. When he says “what Jesus brings especially, that cuts against my temperament, is a special sort of urgency” he makes it clear he fears what may happen if he strays too far from the Holy Mother Church.

And that really puts a damper on the whole book. It takes what is otherwise an imperfect but highly useful argument for the rationality and helpfulness of theistic, supernatural religion in the context of “we can’t know the truth so make an honest effort and be kind to each other” and turns it into a fear-based sales pitch for conservative Christianity.

I would expect a Christian author to make a case for the Christian religion – I’ve done the equivalent in my own Pagan writing. But the first seven chapters of this book led me to expect that Douthat would not argue for the absolute supremacy of Christianity. Certainly other writers have argued more explicitly, but his intent is clear enough.

And so I cannot recommend Believe to Pagans and other non-Christians who are struggling with the question of whether or not they should believe. Instead, I encourage these people to find other resources that will point them in a helpful direction while not implying the author knows what is ultimately unknowable.

Or at least, believes it so strongly he might as well claim he knows it.

Believing is not the most important thing

I’m very sympathetic to the core premise of Believe. I’m eternally curious – whatever the question, I want to know the answer. And if I can’t know, I want to investigate and examine and speculate and come up with the best provisional answer I can.

But Christianity – far more than any of the world’s other religions – puts an inordinate emphasis on belief, especially on believing the “right” things. And so after reviewing a Christian book, I would be an irresponsible Pagan if I did not remind everyone that while what you believe is important, what you do is far more important.

Marcus Aurelius almost certainly did not say it, but it’s still true:

Live a good life. If there are Gods and they are just, then they will not care how devout you have been, but will welcome you based on the virtues you have lived by. If there are Gods, but unjust, then you should not want to worship them. If there are no Gods, then you will be gone, but will have lived a noble life that will live on in the memories of your loved ones.

For Further Reading

Facts and Reason in Paganism – Avoiding Materialist Assumptions (November 2017)

Why I Believe in the Gods (October 2019)

Animism: Relating to Persons Who Aren’t Human (February 2020)

We Are Immortal (August 2020)

A Pagan Look at the Origins of the Universe (January 2023)

Hold Loosely But Practice Deeply (September 2023)