One of the great gifts of the Catholic peace community in this country is a tradition of “public witness” that takes liturgy to the streets. In the 1960’s, Catholic priests Dan and Phil Berrigan made national news when they walked into a draft board office in Cattonsville, Maryland, wearing clerical collars and removed drawers full of draft cards to the parking lot, where they burned them with napalm. They knelt to pray the Lord’s Prayer until they were arrested. The next week, their picture was on the cover of TIME Magazine.

When challenged to justify their extreme action, these priests appealed to the biblical prophetic tradition, asking the public to pardon them for burning paper to insist that we stop burning children. As priests, they understood that symbolic action is never ‘merely symbolic.’ Sacraments, as the church has always taught, are those signs which also convey that which they signify. The sign-acts of the prophets are actions that call us to repentance and the good news of a better way.

I’m glad to get to share this testimony from my friend Patrick O’Neill, a Catholic peace activist who was mentored by Phil Berrigan. He and four others recently stood trial in North Carolina for a symbolic action against the mistreatment of immigrants by local police. This is his account of their witness and trial.

By Patrick O’Neill

During Holy Week 2009, I was arrested along with four others for an act of divine obedience in Alamance County, North Carolina. My crime was attempting to “arrest” of the Statute of Liberty for being an “illegal” from France. Playing the role of an ICE officer, I tried to bring Lady Liberty into custody in the mostly conservative Southern town of Graham, North Carolina, which has chosen to persecute Latinos and frequently deport them for minor traffic violations. We cuffed Lady Liberty and tried to bring her into the jail for processing. After a sit-in, the police eventually let us, and we spent the night.

Three years later, after appealing a judge’s decision against us, we were able to have a jury trial in Alamance County. It was scheduled for Lent 2012. The jury heard testimony from two Graham policemen, a magistrate (who was “trapped” inside the jail for three minutes during our protest) and our three witnesses — Rev. Sarah Jobe, director of Project TURN, a prison based education program; Rev. Spencer Bradford, director of Durham’s Congregations in Action (DCIA), and former Maryknoll missionary, Gail Phares, a co-founder of Witness for Peace, and the coordinator of the annual Holy Week Pilgrimage for Justice and Peace, the event that brought us to Alamance County for the Holy Week 2009 witness that led to our arrest.

Political trials can be and often are intimate events: jurors reveal details of their personal lives, police mingle with defendants, and lawyers talk lots of things over. We were blessed with a wonderful, bright lawyer, Barry Nakell, who was honored by the ACLU in 1990 for his outstanding contributions to civil rights, civil liberties and justice. Alamance County assistant DA Larry Brown was also a gift. Both men wanted to “win” so to speak, but they battled with smiles on their faces. Brown is a good man in the wrong job. He was exceptionally kind to us, as were the Graham cops, who are a very decent bunch of men with whom we chatted during breaks.

Brown made few mistakes, but the one he did make was trying to take on Sarah Jobe for a theological debate. He lost badly. When Brown tried to imply that we were just a bunch of lawbreaking anarchists, Jobe said: “You do have to follow God’s law above man’s law,” adding “287 (g) contradicts God’s law.” She cited 34 Scriptures that call us to welcome aliens, foreigners or sojourners and “treat immigrants as you would the native born.” When Brown said the defendants were expecting to be arrested that day, she replied, “I think we all hoped that they wouldn’t be arrested that day.”

In his closing, Brown said the case was uncomplicated and simple, and that the five defendants were anarchists. “Don’t let (the defendants) confuse you; this case is simple,” Brown told the jury. “Just because you’re quiet when you break the law, doesn’t mean you didn’t break the law.”

After hearing the judge’s instructions, the 12 jurors (“the conscience of the community,” they were told several times) went to deliberate. After about 25 minutes the jurors sent the judge a note asking him for a copy of the 1st Amendment. He called the jury back into the jury box and denied the request. The judge then asked the jurors if they wanted to continue to deliberate or return the next day. They nodded, “Yes” to go home for the day.

At 1:43 p.m. the next afternoon, the jury sent a note to Judge Osmond Smith saying they had reached guilty verdicts for three defendants, but were deadlocked on the two other defendants. When Smith read the note from the jury, I knew immediately that this jury had paid careful attention to a television newscast video shown during our trial. In the video, Francisco Risso, Audrey Schwankl (dressed as Lady Liberty) and myself, are clearly shown blocking the door to the Alamance County Detention Center, while Debbie Biesack and Graymon Ward are sitting in our semi-circle, but clearly not blocking the door. Even though we acted as a community in this action, never wanting to be legally segregated, nine members of the jury concluded that Graymon and Debbie simply did not commit a crime, but Francisco, Audrey and I did.

The three of us were permitted to give sentencing testimony. I spoke of the powerful role civil disobedience has played in U.S. history, from the Boston Tea Party to women’s suffrage to the Civil Rights Movement. I also noted the act of Divine Civil Disobedience by Jesus (that sealed his fate) of the cleansing the temple of the moneychangers.

Francisco, who is now a student at Wake Forest University Divinity School, and who spent years working with Latino immigrants in Morganton, NC, told the court the Jim Crow era and the Holocaust were low points of man’s inhumanity to man, and that our present maltreatment of Latino immigrants was also immoral. “They’re the ones that have the least fault in their poverty,” Francisco said, citing unfair trade practices as a major cause of poverty throughout Latin America.

Audrey said her eyes were opened to injustice when people she knew and loved in her Chatham County community were being hurt and abused by anti-immigrant policies. “When you have relationships with real people … one finds oneself compelled to take action,” Audrey said. I saw her comment as a crystal clear example of why Jesus insisted that we be in relationship with each other — especially with those society calls outcasts. It is out of this communal love that we all come to know God, and find purpose in our lives. “You can’t do nothing,” Audrey said. “You must do something. You have a moral imperative to do something.”

Our lawyer, Barry Nakell, also spoke up, recounting his Witness for Peace trip to Mexico where he saw first-hand the suffering of the Mexican people. “United States policy really creates the immigration that we deplore,” Barry told the court. “We met immigrants and heard their stories.”

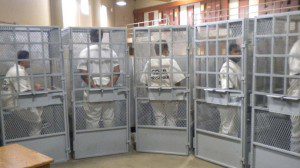

Judge Smith gave each of us 18 months unsupervised probation, 10-day suspended jail sentences, $200 fines, and more than $300 each in court costs. We advised Smith that we could not in good conscience pay the fines and court costs, so he said we would have to serve the 10 days in the Alamance County Detention Center. He gave us until April 9 (Easter Monday) to comply with his sentence or face jail. (We plan to have a “Going To Jail Party” as the date approaches.) It is clear to us that because Latino immigrants do not have the option to buy their way out of jail, we will stand in solidarity with them.

The highlight of the trial for me was the fact that eight jurors stayed for the sentencing (many of them obviously sad to have convicted us) and joined the defendants, assistant district attorney Larry Brown, Barry Nakell, our supporters and the Graham police officers for warm conversation and kind exchanges at the end of the day. My guess is it is quite rare for jurors and the defendants they convicted, the police who arrested them and the attorneys for both sides to all gather post-trial to simply be friendly with each other. It was as if we were all drawn together just to be closer to each other after four emotional and exhausting days together.

Jail awaits the three of us, but for now, as I type late into the night, I feel a sense of jubilation that so many lives were enriched and challenged by the Lenten mysteries that God allowed to unfold. What a gift.