As images of kids at the US/Mexico border continue to feed the 24-hour news cycle, I’m reminded of Birmingham in May of 1963 and the pictures that gripped the nation that spring.

As images of kids at the US/Mexico border continue to feed the 24-hour news cycle, I’m reminded of Birmingham in May of 1963 and the pictures that gripped the nation that spring.

What we’re calling the “border crisis” is today’s Children’s March in the struggle for immigrant justice. The real question is not how to “address the crisis” but rather what the faces of these children demand of us as a country?

In the history of America’s Southern freedom struggle, the Birmingham campaign of 1963 was central. From the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56, black Americans had learned that collective nonviolent action had the power to challenge white power in the South. This discovery lead to conversations and coalitions which gave rise to the sit-in movement of 1960. Especially in Nashville, TN, sit-ins were employed as a direct action tactic in a nonviolent campaign to not only overthrow Jim Crow but also win over white Southerners to a vision of “beloved community.” Mayor Ben West’s public confession that he didn’t think segregation to be morally defensible was a concrete sign that nonviolence could not only defeat segregation. It could create a peaceable community.

But the struggle had to happen in every community. So the nonviolent soldiers who’d been trained in Nashville spread out across the South, joined by others under the umbrella of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In Albany, Georgia, Charlie Sherrod led a city-wide campaign to unite the black community and mobilize them around direct action against segregation. SNCC and its partner, Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, learned important lessons in Albany about the need to plan a campaign carefully and escalate noncooperation to the point that a city’s power structure recognizes the immediate need for change.

This was the collective wisdom the freedom struggle took to Birmingham in 1963. But Bull Conor and the segregationist forces of “Bomb-ingham” proved a tough challenge for the nonviolent movement. Try as they may, they couldn’t crack Birmingham. In seemingly endless meetings, leaders plotted how to escalate the campaign. Despite protests from fellow clergy, King went to jail on Easter weekend, penning his now famous appeal to the white Christians who thought change should come more slowly. But still, Birmingham didn’t budge. (Indeed, it would be 50 years before white clergy responded to King’s letter.)

Then Jim Bevel, one of the nonviolent soldiers who’d been trained in Nashville in 1959-60, brought some kids to King and the other leaders. “These kids want to march,” Bevel said. When they did, Conor’s forces sprayed them with fire houses and chased them with police dogs.

Then Jim Bevel, one of the nonviolent soldiers who’d been trained in Nashville in 1959-60, brought some kids to King and the other leaders. “These kids want to march,” Bevel said. When they did, Conor’s forces sprayed them with fire houses and chased them with police dogs.

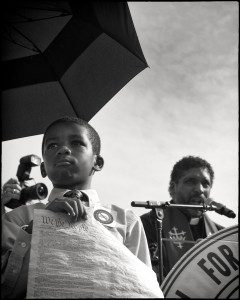

America was shocked by images of children beaten, abused and sent to jail for simply insisting that they too were human beings.

In 1963, the Children’s March woke America to the injustice of Jim Crow segregation. Though it would take a March on Washington and another year of organizing, historians draw a direct line from the Birmingham campaign of ’63 to the Civil Rights Act of ’64.

Looking back, we can see that the Children’s March was central because it forced the nation to ask deep moral questions about what segregation implied for the health of our nation. If, in the name of law, children could be sprayed with fire hoses, could this really be the land of the free and the home of the brave?

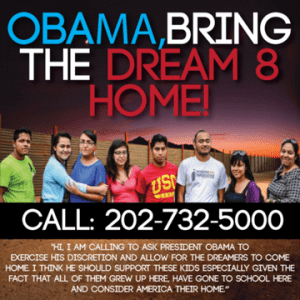

Today, nearly 60,000 children are in detention centers on the US border, locked up as criminals because of free trade agreements and immigration laws that mark them as “illegal.” For some time now, immigrant youth who are inspired by the love of a God who is undocumented and informed by the history of nonviolent struggle in the US have fought deportations, infiltrated detention centers, and boldly self-deported to re-enter the US as asylum seekers.

Just as we can’t understand the Children’s March without reading King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” we can’t understand today’s “border crisis” without hearing the appeal of The Dream 9, who led the #bringthemhome campaign a year ago. Whether they knew it or not, the Dream 9 started 2014’s Children’s March. Now it falls to each of us to discern how we can become a country that doesn’t warehouse children in detention centers but helps them grow up into the fullness of what God made them to be.