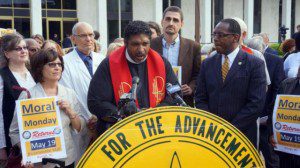

Hundreds of clergy from across North Carolina will gather in Raleigh today to lead the Moral Monday witness, a growing movement organized by the NC NAACP which has brought thousands of protesters to the General Assembly during this session, over 300 of whom have been arrested while petitioning their legislators. Rev. Jimmie Hawkins, a Presbyterian pastor from Durham, NC, organized the clergy witness because, he says, there is a great need for people of faith to say, “We stand with the poor. We stand against any policies that hurt the most vulnerable in our society.”

Rev. Hawkins is right. God’s people need to be here for Moral Monday.

The good news is that God’s people have been at the heart of Moral Monday since its beginnings.

Historians who look back on the black-led freedom movement of the 1960s often note the difference in culture between the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. King and other black ministers, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, led by students who cut their teeth on nonviolent struggle at lunch counter sit-ins and on the 1961 Freedom Rides. SCLC played on the social power of respectable ministers who spoke on behalf of their communities, often in the rhythmic cadence of the preaching style that Martin Luther King mastered. But under the tutelage of Ella Baker, SNCC practiced the adage “strong people don’t need strong leaders.” In the rural communities of Mississippi and Alabama, SNCC field secretaries worked to identify and shine the spotlight on folks like Fannie Lou Hamer and Amzie Moore. These people were God’s children, too. If given the opportunity, they could speak for themselves.

SNCC showed America that the heart of the freedom movement is people who’ve been silenced finding a space to speak for themselves.

The beautiful truth at the heart of Moral Mondays is that all God’s children have been gathering for six weeks to speak for themselves about policies that are hurting them and their communities. The people of North Carolina have not come out to simply complain about bad leadership. We’ve not been organizing in desperate hope for some new, great leader. No, we have been speaking as clearly as we know how the truth that God speaks to each of us: “You are my beloved, with whom I am well pleased.”

Because we are loved, we are called to be our brother’s keeper. And because so many of our sisters and brothers are hurting, we cannot keep silent.

This is, of course, the heart of the message that clergy are called to preach in our communities each week. As keepers of our truest story, clergy in their robes and collars need to be among those speaking out and, if necessary, going to jail.

But I’ve been a preacher long enough to know that those of us who aim to preach God’s word are often prone to talk too much (I started preaching when I was sixteen, so I’ve done my fair share). I suspect this movement doesn’t need us to lead as much as it needs us to follow–to listen carefully, to pray fervently, and to ask how what is happening before us is rooted deeply in the story of what God has been doing since the foundation of the world.

Last night here in Durham, we had a wonderful performance of The Best of Enemies, a play about the unlikely friendship between a militant black activist, Ann Atwater, and a local KKK leader, C.P. Ellis, who both realized that their fears and hatred of one another were keeping them from helping their children find a better future. In a striking scene toward the end of the play, Atwater visits Ellis in his hospital room, where he confesses that he almost killed a black man when he was working with the Klan.

“I almost killed a man, too,” Atwater says.

“Oh yeah,” Ellis replies. “Who was that?”

“You,” she says.

Ann has been my mentor here in Durham for years, and I’ve heard her tell the story of how she pulled her knife out of her purse and stood up in a City Council meeting once to go cut C.P.’s head off. What stopped her? It was the hand of her pastor–the man who preached the radical love ethic of Jesus on Sunday, but was also there behind her on a Monday evening, watching and praying. He leaned forward and whispered in her ear, “Don’t do it, Ann. Don’t let him get to you.”

I reckon every movement needs its pastors. Sometimes up front, letting everyone see that the church is present. But just as often in the crowd, whispering the gospel in a sister’s ear. And following where only she can lead, one step at a time.