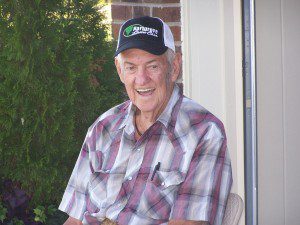

On Friday, September 27th, my grandfather, Alvin Wade Hartgrove, died. His funeral on Monday was part family reunion, part Baptist church homecoming, and part biker rally. I was grateful to get to offer this eulogy.

On Friday, September 27th, my grandfather, Alvin Wade Hartgrove, died. His funeral on Monday was part family reunion, part Baptist church homecoming, and part biker rally. I was grateful to get to offer this eulogy.

Well, I wasn’t here to see it for myself—as a matter of fact, there aren’t many left who were here to witness it firsthand—but I’ve heard it told that everyone in these parts was a little worried when Alvin started driving. It’s not in the official record, of course, but some say he fudged his age to get a license early. He had an old motorcycle, and he took every curve as hard as he could. He loved to watch the mufflers spark as they hit the pavement. People tell me he was always like that.

Like I said, I wasn’t around to see it myself, but I do remember riding with my brother, Josh, when he was learning to drive on these same mountain roads half a century later. I’ll never forget the day he was taking a curve hard on the ride home from South Stokes High School. The tires didn’t hold and we slipped off the edge. As Josh jerked the truck out of the ditch, we spun around and stopped in the middle of the road, facing the on-coming traffic. I reckon it goes without saying that Josh has a little of Alvin in him.

But back in the late 40’s, when everyone in these parts was worried that Alvin Hartgrove was going to wrap himself around a tree, I’m told there was an old farmer who built a big haystack back of the curve in front of his house. “If you keeping driving that way,” he said to Alvin, “you’re gonna go over the edge. I figured I better put a haystack there to catch you.”

Alvin Wade Hartgrove had three sons, two of whom had two sons. I am the second son of his youngest, Clint, so I always knew Alvin as Grandpa. The Bible says it is not good for man to be alone. As a male in the third generation of a family that only had boys, I confess I’ve proven the truth of this on more than one occasion.

There were four of us boys in my generation. We inherited, among other things, Grandpa’s love for guns. One afternoon, while taking target practice by the wood pile at our cousins’ house, a BB ricocheted off a tree and hit one of us. I don’t remember who was shooting or who was hit, but I do recall that it was all-out war for the next thirty minutes. We were ducking behind trees, rolling over the woodpile, and hollering at each other like men on the beaches of Normandy. When it was all over, I remember standing in my parents’ bathroom, my momma pulling a BB out of my arm with tweezers.

“What in the world were you thinking?” momma asked. “I guess I just got carried away,” I said. Maybe there was a little of Grandpa in all of us.

You don’t take every curve hard without going over the edge sometimes. And you don’t go over the edge of life without hurting others, without hurting yourself. Grandpa wasn’t a perfect man. He had his wounds, and I am sure he inflicted some on others. I suspect no one knows this more than you do, Phyllis. You stood by him and loved him for almost thirty years. I’m sure it wasn’t always easy, but it seems to me that you were a haystack in his life—catching him after he’d gone over the edge of two marriages and holding him in love. You helped him to reconnect with his sons and grandsons, and so he was able to know and love his great grandchildren. You loved him to the end. For that, I thank you.

Jesus told a story about a man who had two sons. The younger of them was the sort of guy who liked to take curves hard. I suspect, like Grandpa, he loved the color red. He probably drove a motorcycle. When he was still young and wild, he went to his daddy and told him that he wanted his part of the inheritance. He went off to a far country and squandered Daddy’s wealth, squeezing all he could out of life while he racked up a hefty debt. In short, he went over the edge.

At his lowest point, when he was down in a pig pen, slopping the hogs, this fellow found himself so hungry that he was thinking about eating the pigs’ food. In this moment of desperation, he came to himself. “Wait a second,” he said. “Daddy has servants who are better off than me. Maybe if I go home, begging and pleading all the way, he’ll let me join them and eat at their table.”

So all the way home, he practiced his little speech. “I’ve sinned against heaven, and I’ve sinned against you. Please, oh please, if I could just live with the servants. I know I don’t have a place at your table, but if I could just eat the leftovers from the servants’ table….” And so on. All the way home, he was practicing his penance.

Most people call this the tale the parable of the Prodigal Son. I reckon it’s because most of us think this is a story about how wrong-headed and stubborn some of us can be. We think it’s a story about those people who tend to take curves too hard, who end up over the edge. But that’s not what Jesus said. Jesus started this story by saying, “There was a man who had two sons….” For Jesus, this was always a story about a daddy’s love for his children.

Which is why, while his son was still a long ways off, Daddy saw him coming. Sure, his son had been gone a while. But Daddy never stopped looking for him. And when he saw his son coming home, he took off running to great him. The son fell down on his knees and started into his little speech, but Daddy cut him off. “Go get my finest red robe! Put a big shiny ring on his finger! Kill the fatted calf,” Daddy said, “for my son who went over the edge has come home.”

Now, there are plenty of gods in this world, and you can choose to believe in anyone one you want. But the only God I believe in is the One who loves us like this Daddy loved his son. People make mistakes. The pain we inflict on others in this world is real, and sometimes it is greater than we can imagine. You don’t have to forgive prodigal sons. You can lock them up and throw away the key. You can spend all of eternity judging them for the worst mistakes they’ve made. But you can’t ignore a Daddy’s love that says, “Forget all that. My son who was lost has come home. I love my boy. Thank heavens, he’s home. We’re gonna have a party.”

I’ll have to admit, this is the point in this story when the facts get a little hazy. The final report isn’t in, so I’ll confess that what I have to say is based mostly on hearsay. Still, I tell it because I believe it to be true.

Early this morning, just about daybreak, I went out walking by mom and dad’s house. While everything was still, I decided to wander over by the Pearly Gates and poke around a bit. Of course, I know better than to get too close. I’m none too eager to meet St. Peter myself. But I wandered over that way to see if I might hear anything.

Sure enough, over that way, there was an old feller leaning on a fencepost, just gazing out over the fields. “Nice day,” I said, and he replied without turning his head, “Sure is.”

He looked like the sort of feller who likes to talk, and being the type of feller who likes to listen, I decided to stop and stand there with him for a minute. “Always like to get over here this time of year,” he said. See them blue mountains and those tobacco fields after the plants are stripped bare, when it’s cool and clear on a morning like this.”

“God’s country,” I said to him.

“Yep,” he says. “You’re right about that.”

“You say you always come over this time of year?” I asked him, and he said yes, he liked to. Then, after a pause, he started in again.

“What got me over here to start with was that commotion on Friday night. I didn’t see it myself, but somebody over this way told me he saw what looked like a shooting star flying over the gates, only it sounded like an engine revving as it flew through the night sky. Next morning, low and behold, they found a Honda Gold Wing, all red, with its headlight still on. I came over to see it for myself, and this other feller I ran into said he’d heard it too, and above the roar of the engine, he just knew he heard somebody cackling.”

“But the strangest thing,” he said to me as he turned his gaze from the mountain to look me in the eyes, “the strangest thing of all was this: that bright red motor cycle with its headlight still burning was sitting upright, just as pretty as you please, right smack in the middle of a haystack.”