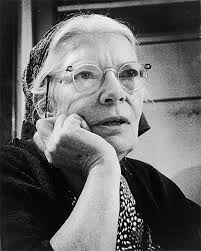

33 years ago today, Dorothy Day died at the Catholic Worker in New York City where she had lived and worked for almost half a century. “Don’t call me a saint,” she had said. “I don’t won’t to be dismissed so easily.”

33 years ago today, Dorothy Day died at the Catholic Worker in New York City where she had lived and worked for almost half a century. “Don’t call me a saint,” she had said. “I don’t won’t to be dismissed so easily.”

But already in 1980 those whose lives she had touched knew there was something of the living power of Jesus in Day’s life. “A light shines in the darkness,” John’s gospel says, “and the darkness has not overcome it.” For many who knew Day, her life was a source of light as they found their way through the dark.

Though Day is often celebrated by more progressive Catholics because of her commitment to nonviolence and the poor, conservative bishop Timothy Dolan has taken up her cause for sainthood. Still, Day’s influence is not limited to the Catholic Church. At last year’s National Prayer Breakfast, President Obama heralded Day, alongside Martin Luther King and Jane Adams, as a “great American reformer” whose faith inspired her work for social change.

I never knew Dorothy Day, but I have felt a special connection with her my whole adult life. I was born on her birthday in 1980, the same year she died. As a young Baptist trying to understand how Jesus wanted me to engage the world after becoming disillusioned with the Religious Right, I saw Day’s witness as a guiding light. Our political backgrounds couldn’t have been more different, but from the extremes of America’s political landscape we were drawn to the same radical alternative in the politics of Jesus. Day’s commitment to both live and write this vision became a guide for me.

“Heaven is a banquet, and life is a banquet too,” Day wrote, “even with a crust where there is companionship.” She saw clearly in the midst of America”s Great Depression that our greatest poverty was not a lack of resources but of relationship. In 1933, after starting a newspaper to promote the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Day founded a hospitality house to welcome Jesus through the traditional works of mercy. “If every Christian home had a Christ room to welcome our Lord, no one would be homeless,” Day said. But she didn’t welcome the stranger to end homelessness. Day trusted that, as Jesus had promised, he would come to her in the distressing disguise of the poor.

But she didn’t for a moment romanticize poverty. Day knew that Jesus was among the poor because he loved people, not because he loved poverty. Poverty, she saw clearly, is a symptom of social sin. A journalist by profession, Day chronicled the realities of poverty and injustice for five decades. She participated in direct action, refusing to bow to any law which fell short of God’s law. We have a picture of Day on our wall at Rutba House–a seated grandmother at a workers’ protest, framed by two police officers. The guns on the officer’s hips are large in the foreground, but Day is a more formidable presence. You wouldn’t want to mess with her.

This month, I published Strangers at My Door: A True Story of Finding Jesus in Unexpected Guests. It’s a collection of stories about the people I’ve known in a hospitality house over the past decade. It’s a book about meeting Jesus in the distressing disguise of the poor. It’s a book about finding the community we all long for. And it’s a book about how the homeless can help us see more clearly the injustices that plague our society.

The good folks at Random House decided to publish Strangers during Homelessness Awareness Month, and I’ve been grateful for the conversations that has made possible. But I think some higher power may have been at work in this book coming out during the month that Dorothy Day was born and died. Both my life at Rutba House and my life as a writer would be unimaginable to me without the witness of Dorothy Day. More importantly, because of Dorothy Day’s witness, I know the power of stories to interrupt our darkness, even on Black Friday.

A light shines in the darkness, and it is shining still.