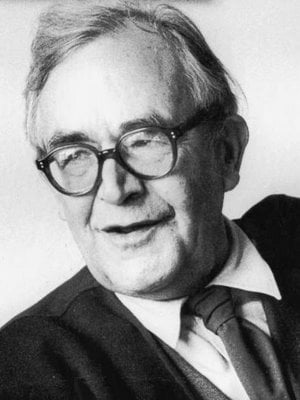

Recently, some discussion has arisen on the blogosphere surrounding Karl Barth, and in particular, his odd relationship to Charlotte von Kirschbaum. Though for some time the exact nature of the relationship between Barth and his secretary was subject to speculation, recent publications have demonstrated what has been assumed: this was an adulterous relationship, almost certainly sexual in nature. Bobby Grow of the Evangelical Calvinist blog has written several posts on the topic, discussing his frustration with the obvious immorality in Barth’s life [1]. William Evans has added some of his own thoughts on Barth on the Ecclesial Calvinist blog [2]. The question which arises is at this juncture is whether the immorality of a teacher has any impact upon the benefit of their teachings. While some have argued that it is irrelevant, as the truth or falsity of one’s teaching is not dependent upon anything within the character of that person, Grow has noted that the nature of such immorality is a Biblical disqualification from having a teaching position in the church. Certainly, no teacher is immune from criticism. Luther is often derided for his attitude toward Judaism, and Calvin for the manner in which Geneva punished heretics under the civil law. Yet, Barth’s flaws do seem different, as he was well aware of the sinful nature of his situation, and was also warned about it by Bonhoeffer and others. Yet, he remained unrepentant in such a lifestyle until his death. Whatever conclusion one comes to on this point, I am convinced that it is not all that great of a loss if one does reject the teachings of Barth. In my opinion (whatever that is worth), Barth is quite the overrated thinker.

Recently, some discussion has arisen on the blogosphere surrounding Karl Barth, and in particular, his odd relationship to Charlotte von Kirschbaum. Though for some time the exact nature of the relationship between Barth and his secretary was subject to speculation, recent publications have demonstrated what has been assumed: this was an adulterous relationship, almost certainly sexual in nature. Bobby Grow of the Evangelical Calvinist blog has written several posts on the topic, discussing his frustration with the obvious immorality in Barth’s life [1]. William Evans has added some of his own thoughts on Barth on the Ecclesial Calvinist blog [2]. The question which arises is at this juncture is whether the immorality of a teacher has any impact upon the benefit of their teachings. While some have argued that it is irrelevant, as the truth or falsity of one’s teaching is not dependent upon anything within the character of that person, Grow has noted that the nature of such immorality is a Biblical disqualification from having a teaching position in the church. Certainly, no teacher is immune from criticism. Luther is often derided for his attitude toward Judaism, and Calvin for the manner in which Geneva punished heretics under the civil law. Yet, Barth’s flaws do seem different, as he was well aware of the sinful nature of his situation, and was also warned about it by Bonhoeffer and others. Yet, he remained unrepentant in such a lifestyle until his death. Whatever conclusion one comes to on this point, I am convinced that it is not all that great of a loss if one does reject the teachings of Barth. In my opinion (whatever that is worth), Barth is quite the overrated thinker.

I have read a lot of Barth. I’ve gone through six volumes of the Church Dogmatics, and I’ve read many interpretations of his thought from Hunsinger, McCormack, and others. My opinion is not, then, out of ignorance, but out of a significant amount of time with both primary and secondary sources. Barth, without doubt, is a brilliant thinker who is well-versed in both theology and philosophy. In that regard, I certainly understand his impact. However, there are some significant problems with his thought.

My first issue with Barth is simply his obscurantism. I often have found that when reading the CD, there seeming contradictions even within the span of a few pages. Many passages seem purposefully obscure, which is the cause of so many interpretations of Barth. After reading these varying interpretations, it is clear that nearly all of them can genuinely utilize passages from from Barth. I’m convinced that the problem is not so much in the interpreters, but in Barth’s own writing. One of the reasons I have recommended the reading of scholastic theologians is that they speak in clarity, with no doubt on exactly where they stand on various issues. The fact that no one can quite agree on whether Barth even believed in a literal historical resurrection is quite telling. For some odd reason, such confusion seems to be a hallmark of influential early twentieth century writers. A read of Heidegger will lead one to the same frustrating conclusion that his writings are simply impenetrable.

Second, despite all of his advances past nineteenth century liberalism, Barth has not overcome the fundamental problems with Kant’s impact upon liberal theology. Whether intended or not, his denial of natural theology seems to imply an adoption of Kant’s noumenal/phenomenal divide. God cannot reveal himself in the ordinary things of nature to the human subject, and thus must do so supernaturally through the event of revelation, which occurs directly between God and the human person. By proclaiming “nein!” to natural theology, and divorcing Christian truths from any verifiable testable history into the realm of suprahistory, Barth never really countered the problems with the liberalism he fought against. He merely sidestepped them.

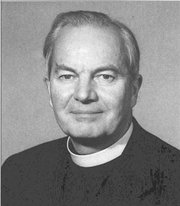

Third, there are simply better theologians within the neo-orthodox tradition. Brunner, for example, is able to give many insights of Barth and criticisms of liberal theology without the need for such obscure phraseology. A read of his three-volume treatment of Christian theology leaves absolutely no doubt as to where he stood on various issues, which is perhaps why there has not been much scholarship on his thought. The confusion of Barth’s words, I think, are part of the appeal for many. Brunner is also not willing to simply throw out the category of natural theology altogether, wh ile simultaneously recognize its limitations. Torrance is, in my opinion, the best voice within the Barthian tradition. He takes Barth’s best insights, clarifies them, and infuses an extensive knowledge of Patristic theology into them. If any one of the neo-orthodox thinkers can speak clearly to the church today, I would argue that this is Torrance, not Barth.

ile simultaneously recognize its limitations. Torrance is, in my opinion, the best voice within the Barthian tradition. He takes Barth’s best insights, clarifies them, and infuses an extensive knowledge of Patristic theology into them. If any one of the neo-orthodox thinkers can speak clearly to the church today, I would argue that this is Torrance, not Barth.

I am not a proponent of neo-orthodox thought myself. I see significant problems with their limited view of revelation, and I am convinced that a divorce between the Holy Spirit and the means of grace has lead to an extremely low sacramental theology on behalf of this tradition. However, I do recognize that there are benefits to these writers–particularly in their critiques of Schleiermacher, Ritschl, and other leading voices of Protestant liberalism. I have been especially encouraged by Torrance’s emphasis on the centrality of the incarnation and use of Eastern ideas in his soteriology. I simply think that Barth himself, while the most important writer for the movement historically, is overrated.

Of course, I am a Lutheran who’s not convinced that Martin Luther is the best theologian in my own tradition, so maybe the oddity is not so much Barth as it is me.

[1] https://growrag.wordpress.com/2017/10/01/my-final-post-ever-on-karl-barth-and-charlotte-von-kirschbaum/

[2] https://theecclesialcalvinist.wordpress.com/2017/10/02/why-i-still-dont-much-care-for-karl-barth/