Growing up in the Southern Baptist church, the only holidays on the liturgical calendar in my world were Christmas and Easter. I’d never heard of Lent or Advent, I wasn’t even aware that there were days and seasons throughout the year to commemorate different parts of the church’s life.

As an adult, I lead worship at a Cooperative Baptist Church that practices more liturgically than any of the churches I grew up in, and it’s become a part of my life to examine what Lent, Advent, Easter, Christmas, Pentecost, and other holy days and seasons are meant for.

Native culture is full of sacred seasons as well, and the more that I learn about indigenous ceremonies that my tribe and others commemorate throughout the year, I see connections between indigenous culture and biblical culture in a way that only increases my capacity for faith and the beautiful diversity of God.

We commemorate Pentecost Sunday the seventh Sunday after Easter, the day that the Holy Ghost fell on the people of the new testament church. But this church holiday has other meanings and names as well. Some connect it to Shavuoth, the Jewish celebration commemorating the time when God presented the Torah to the Jewish people, or Whitsunday, another name for Pentecost celebrated by churches in the UK and in Anglican and Methodist churches. Whitsunday is also connected to Beltane, a historic summer festival in Ireland and Scotland.

What connects these church holidays is not just that we remember the Holy Spirit coming alive in the people of our bible stories, but we see a thread of customs, celebration, and ceremony coming alive across cultural boundaries and histories.

Shavuoth, a two-day Jewish celebration, consists of pilgrimages, large feasts, eating dairy, and decorating homes, among other things.

To celebrate Whitsunday there are parades and festivals, and in some cases, commemorations of Beltane, which is often considered a “pagan” holiday but also a celebration of the coming of summer. In a Beltane ceremony, there are prayers and feasting, words of peace and togetherness, a lot like the Jewish celebration, a lot like our Baptist potluck dinners and laying on of hands to pray and embrace one another.

So you see, there is a sacred thread of ceremony throughout these holidays, and I see more and more a connection to the sacred ceremonies of Native peoples, not unlike the druid ceremonies practiced throughout history. Maybe the church calls it “liturgy,” the holy word for those things that others might call “ceremony.”

In the Christian faith tradition, sometimes we push aside the idea of ceremony, especially ceremonies that we deem to have some connection to “idolatry.” This created distance is riddled throughout our faith history, and in relationship to indigenous people, it is no secret that ceremonies and traditions were banned, and native peoples were punished or even killed for celebrations and festivals that were important to their spiritual life.

In the same way, the connection to druid “pagan” ceremonies gives this particular church holiday a chance to embrace a connection through the Spirit to creation and community, and to another culture. This is what I missed in the church growing up which was a tradition based on checklists and beliefs, not on practicing any sort of grounding work besides a daily quiet time and bible study. As an adult, I need to be tethered to God through ceremony, through commemorating the changing of the seasons and life cycles, through the church’s holy days and my own culture’s holy days.

We do not forget that we are to be people of ceremony, celebration, and festivity. Sometimes when we read the words of the New Testament about putting away the old laws, we also put away the ceremony and celebration of the Old Testament, pieces that perhaps were not meant to be thrown away at all. And throughout the transformation of Christianity over time, we tell other people that their ceremonies aren’t allowed, either.

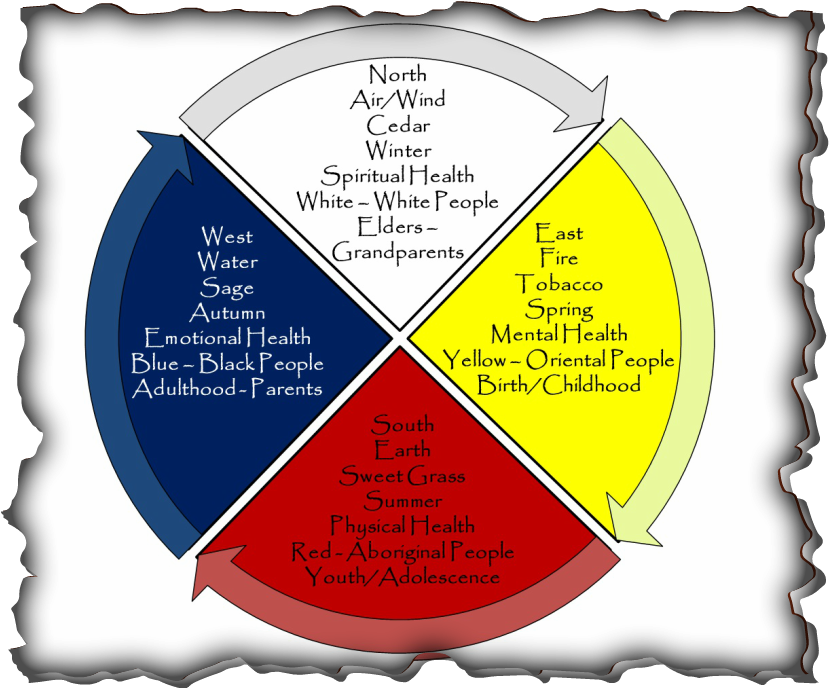

At our church, we will wear red on Pentecost Sunday. Red may be the color that reminds us of Pentecost, of fire and flame, but because I seem to be learning what the bible means through a native lens, I wonder, then, what the red of Pentecost might mean for me, a Potawatomi woman whose tribe literally means “people of the place of fire.” Red, the color of the South on the Medicine Wheel, a tool used by Native Americans to understand life seasons. Red, the color of the earth, the color of summer, the color of youth and vigor.

So I remember that on Pentecost Sunday, the Spirit of God came to earth, the fire of God called life out of and breathed life into the people. I remember that as summer comes, we see the Spirit all over this world in the things that bloom, in the hot summer sun, just like those worshippers in the Beltane festival do. And I see that the renewal, a youth-like newness comes with the Spirit’s voice, and we know that we are not alone.

And if we are not alone, then the goodness and all-inclusiveness of Jesus and the whoosh of the Spirit is alive and well in our ceremony—in our dancing, in our praying and smudging, in our fall fire ceremony when we welcome in the cool weather by keeping a fire lit for four days, in the naming ceremonies we use for our children. The Green Corn Ceremony, a time of harvesting corn and reconciling with our brothers and sisters, reminds us that the Spirit of God is alive and well in the people when we practice harmony and shalom toward one another. When Native ceremonies were outlawed by the church and the government, pieces of our cultures were stripped from us.

If the people of the new testament heard that day strangers speaking in their own native tongues, is that not a sign that the Spirit of God moves in us in our own native cultures as well? While the Spirit is something so other that we cannot fathom it, we are somehow comforted by the fact that we are accepted in its embrace, known in our own skin and understanding.

And when the church deprives itself the joy of embracing celebration, tradition and ceremony, it is stripped of something so needed in its identity.

The Spirit that fell that Sunday called the people into a unity, into a newness, into the light.

We are still called, all of us, in all our unique understandings, in all our cultural lenses.

That is the whole-beauty of Pentecost, WhitSunday, Shavuoth, Beltane, The Green Corn Ceremony, and so many others that celebrate God in relationship with people, with creation, with what has always been called good.

Happy Pentecost, friends.

{resources: