I’ve only seen the first episode of HBO’s five-part scripted series Chernobyl, which premiered May 6, but one thing is immediately apparent: the Communist government of the then-U.S.S.R. was determined to never admit reality, even in private.

In the immediate aftermath of the April 26, 1986, explosion and fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the northern Ukraine city of Pripyat, the plant supervisor dismisses whatever negative news that doesn’t fit the narrative that his engineers tell him. The local party bosses then do the same, exhorting their fellow faithful to cling to a belief in Soviet socialism, which will somehow make everything OK.

A combination of poor procedures and design led to the incident, which caused a fire that lasted for over a week and spread radiation 250 miles away. Amazingly, the area — currently overrun with plant growth and wildlife — has become a tourist attraction for the former Soviet republic.

What is the Chernobyl miniseries about?

Created and written by American Craig Mazin and directed by Swede Johan Renck, the drama centers on a real-life character, Valery Legasov (Jared Harris, King George VI in The Crown), the Deputy Director of the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy, part of the team that investigated the accident. He left behind a rare glimpse into the inner workings of the Soviet nuclear-power industry, the government and its persistence in pretending that all was well.

This past summer, at the biannual TV Critics Association Press Tour, I heard Mazin and others discuss Chernobyl.

Mazin, who says that, for environment reasons, he is supportive of the modern nuclear-power plants we have in America, wanted to opt for truth over drama.

Here are some highlights of what Mazin had to say:

On the choice between drama and truth:

This is as close to reality as we can get and still be able to tell the story in five episodes. It was our obsession, and certainly our intention all the way, to be as accurate as we could be. The simple rule that we had, if we were going to change something, it had to be only so that we could tell the story fully. We never changed anything to make it more dramatic than it was, to hype anything, to amp it up. For us, this is a story about truth. The last thing we wanted to do was fall into the same trap that liars fall into. This is very much a well-researched factual dramatic representation.

There are certain cases, because we’re dealing with an incident that occurred in a nation that no longer exists, a nation that was not particularly known for its openness, that there are some competing narratives. I tried as best I could to go with the ones that seemed to most true, not necessarily the most dramatic. There is an incident — I won’t say specifically what it is — most people report it in a much more dramatic way than it actually occurred. I went with the less dramatic way because it’s true. So that, in general, was our motivation.

On what happens when appearances are more important than facts:

When you watch the series, you will realize how difficult it is to make a nuclear reactor explode. There have to be errors in judgment and intentional lies and disassembly from levels from the very top all the way down to individual people in a room. That said, to me, the cautionary tale here is bigger than just the nuclear power industry, or even the environment. The cautionary tale here is about what happens when people choose to ignore the truth. As it turns out, the truth does not care.

On what has happened in the wake of Chernobyl:

This is a period piece that essentially extends from April of 1986, roughly to April of 1988. Russia is a different nation than the nation that built and ran Chernobyl. Sometimes we forget a little bit how big the Soviet Union was. For instance, Chernobyl itself isn’t even in Russia — it’s in Ukraine. And, it’s in very Northern Ukraine, right up against Belarus. So, I would hope that the changes that occurred in the aftermath of Chernobyl — in no small part because of the actions of scientists like Valery Legasov — have remained in place.

But we do know, for instance, that when Lithuania joined the EU, one of the conditions was that they decommission the reactor at Ignalina because it was the same type as the reactor at Chernobyl. I think there’s one facility left in Russia that is still using the RBMK (a Soviet design of nuclear reactor), but I think that is scheduled to be phased out as well.

On the difference between our nuclear plants and Chernobyl:

We’re in pretty good shape here. In a strange way, researching this story made me feel slightly more comfortable about the nuclear-power industry, at least here in the West. For instance, here in the West, all of our nuclear-power plants are inside of containment buildings. This is why, when Three Mile Island had a partial meltdown, almost no radiation escaped into the atmosphere. You know, minimal. In the Soviet Union, there was no building around them at all.

We also use a very different kind of reactor here. In the Soviet Union, those reactors were designed to be built to supply massive amounts of power at low expense. But in doing so, they used a design of a reactor that kind of wanted to get hotter; and the reactors that we use here, in sort of very elementary terms, they want to get colder. So, I we should be OK here. That said, I predict things all the time that don’t come true. So, I hope we’re OK.

On what he learned:

Chernobyl was the product of intentionally terrible decisions designed to protect a system that was inherently corrupt and inhumane. And it was also the result of individual humans doing the things that individual humans often do. What I found so oddly beautiful about the stories that I read, was that in response to what I would consider to be the worst of human behavior, we saw the best of human behavior.

Only humans could have made Chernobyl happen, only humans could have solved the problem of Chernobyl. The nobility, the quiet nobility, of hundreds of thousands of people, names of whom we will not know, is remarkable.

Chernobyl (official site here) airs Mondays at 9 p.m. ET/PT on HBO; episodes also available to stream on HBO NOW and HBO GO.

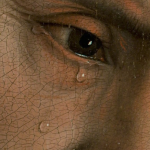

Image: HBO

Don’t miss a thing: Subscribe to all that I write at Authory.com/KateOHare.

And, head over to my other home, as Social Media Manager at Family Theater Productions; and check out FTP’s Faith & Family Media Blog, and our YouTube channel.