What the heck was Jesus talking about, anyway?

What the heck was Jesus talking about, anyway?

I mean, he’s holding up a piece of bread and he says, “This is My Body.” Does that even make sense?!

Ask any group of Christians in your workplace or in your neighborhood what Jesus really meant, and chances are you’ll get a broad range of answers. Their explanations may follow strict denominational lines; but even within church communities, you may find people who draw different conclusions about this singularly important tenet of the Faith.

- Some people will tell you that Jesus really meant that we should have a little ceremony, like he did, and that when we repeat his words we should think about him and about his saving act of dying on the Cross for us. For those people, the Eucharist is a memorial.

- Others will say that the bread represents Jesus himself. For people in this camp, the Eucharist is a symbol.

- Some denominations teach that the bread and the wine actually become the Body and Blood of Christ, but that they’re still bread and wine, too. They call this “Consubstantiation”—the bread is both bread and Body. This belief in the “sacramental union,” the belief that the Body and Blood of Christ are present “in, with and under” the elements of bread and wine, is held by Lutherans.

- Roman Catholics and others acknowledge that the bread and wine have truly become the Body and Blood of Christ. Further, they insist that despite appearances, they are no longer bread and wine at all. This is called “Transubstantiation,” since the substances are actually transformed. For Catholics, the Eucharist is a sacrament—a symbol and reality which draws the believer closer to God.

But while Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox say that the Eucharist is a “sacrament”—a symbol which actually imparts grace—some Protestants insist no, it’s an “ordinance”—not imparting grace to those who receive, but rather expressing faith and showing our obedience to Christ.

Reformed churches, which adhere to the teaching of John Calvin, have an even lower view of the Eucharist. According to Reformed believers, Christ is present in the Eucharist in only an immaterial, spiritual (or “pneumatic”) way—present by the power of the Holy Spirit, and received by faith.

And Anglicans—well, they’re all over the board on this, with individual congregations defining their own creedal statements, although their Articles of Religion support the Reformed theology.

* * * * *

OK, so where are we going with this? Isn’t this one of those areas where we can just agree to disagree?

OK, so where are we going with this? Isn’t this one of those areas where we can just agree to disagree?

Jesus didn’t think so.

Do you remember when Jesus first introduced the idea of eating his flesh? In John 6:53, he said,

“I tell you the truth, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you.”

And what happened then? Many were troubled and turned away, and walked with him no longer. Jesus lost many followers with this hard saying; but he didn’t say “Wait, guys, I was only kidding!” He didn’t call them back, explaining that he was speaking only metaphorically. Nope, Jesus let them go. It was too important that his followers fully understand the great gift he was about to leave for us, the gift of himself.

This is in sharp contrast to Jesus’ reaction in Matthew 16:5-12. Talking about the Pharisees and the Sadducees, Jesus warned his disciples concerning the “leaven” of these two sects. In this instance, Jesus’ followers thought he was speaking literally—that he was speaking of the bread they had forgotten to bring for their journey. This time, Jesus didn’t just let it go; he rebuked them for their lack of faith. Had they not remembered the feeding of the 5,000 and the feeding of the 4,000, and the amount of leftovers in each case? They then understood that Jesus was not speaking of literal bread, but rather, of the teaching of the Pharisees and the Sadducees, which spread easily and was dangerous.

* * * * *

If the Bread of Life discourse were only metaphorical, then Paul would have been greatly overstating his case when, in 1 Corinthians 11:27, he says:

If one eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner, he will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord.

In a Semitic culture, to be “guilty of another’s body and blood” is to be guilty of murder. Yet how could one be guilty of murder if the bread is merely a symbol of Christ? No, Paul is dead serious—in fact, he warns that this is such a serious sin that some are dying because of it.

* * * * *

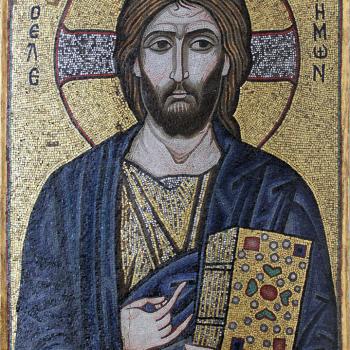

St. Ignatius, one of the early Church Fathers, wrote of his faith in the Real Presence in his letter to the Romans (A.D. 110):

I have no taste for corruptible food, nor for the pleasures of this life. I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, who was of the seed of David; and for drink I desire his blood, which is love incorruptible.

St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, offered the following prayer after Holy Communion:

Oh Christ our God, You have deemed me worthy to be a partaker of Your most pure Body and most precious Blood.

I praise, bless and adore You; I glorify You and extol Your eternal salvation, now and ever and forever. Amen.

For John Chrysostom, the Eucharist was so sacred that no one should approach to receive the body and blood of Christ unworthily. In his Homily 20, he wrote:

As it is not to be imagined that the fornicator and the blasphemer can partake of the sacred Table, so it is impossible that he who has an enemy, and bears malice, can enjoy the holy Communion….

I forewarn, and testify, and proclaim this with a voice that all may hear!

Let no one who has an enemy draw near the sacred Table or receive the Lord’s Body! Let no one who draws near have an enemy! Do you have an enemy? Do not draw near! Do you wish to draw near? Be reconciled, and then draw near, and touch the Holy Gifts!