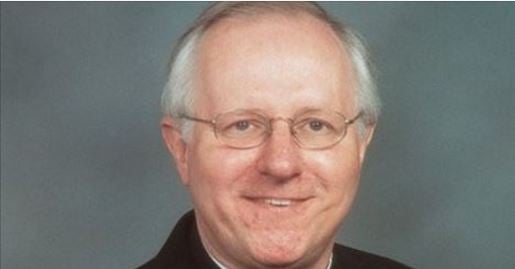

Father Emil Kapaun, U.S. military chaplain during the Korean War, was captured on November 2, 1950.

Two days later and twenty miles away, Lieutenant Bill Funchess was captured by the Chinese Communist Forces and taken to a prison camp, where he was thrown into a 9-by-9-foot thatched roof mud shack. There, lying in the cold on a dirt floor, were eleven seriously wounded enlisted men.

Emil Kapaun, a Catholic priest, died in that camp; his fellow soldier Bill Funchess, a Methodist, became Father Kapaun’s friend and caretaker in the last weeks of his life.

Sixty-three years later, Bill Funchess remembers like it was yesterday; and he welcomed my questions, talking openly about his experiences as a prisoner of war in a Valley Camp in North Korea.

Father Kapaun and Lieutenant Funchess were both forced by their captors to march north; but the two were imprisoned in different compounds, and it wasn’t until February 1951 that they actually met. Funchess had been permitted out for a rare walk in the camp. Funchess was searching for something to eat when he stumbled upon a man who had kindled a fire, and who was melting snow in a roughly crafted tin pan. “Would you care for a drink of water?” asked the man. “Yes, I certainly would,” exclaimed Funchess. The priest gave him about half a cup of water, and Funchess still remembers his kindness. “I’ve never tasted anything so good,” he explained, adding that it was the first water he’d had to drink since his capture. Until then, he and the other soldiers had survived by eating snow.

Within a week, Father Kapaun climbed the fence into the compound where Funchess lived, where the priest helped many of the sick and wounded prisoners. Shortly after, Chinese officers realized, though, that Funchess was an officer living among enlisted men; and he was relocated to an officers’ camp, again separated from Father Kapaun.

But in April 1951, the door to Funchess’ shack was thrown open by Chinese guards, and a man was thrown to the floor. It was Father Emil Kapaun, who was suffering from a blood clot in his right leg and was having difficulty walking. Perhaps, said Funchess, the guards hoped to isolate him from the Catholics, in the mistaken belief that prisoners of other faiths wouldn’t bond with him. Perhaps, too, they hoped that the prisoners in that hut would care for Father Kapaun.

The priest, the only Catholic whom Lieutenant Funchess had gotten to know, was an inspiration to his fellow prisoners. When he was able to walk, he cared for the other POWs with no regard for their faith background; Catholic, Protestant or atheist, all were the recipients of Father Kapaun’s kindness.

Lice were a significant problem for the prisoners, sucking their blood; and a soldier who didn’t pick lice from his body could lose a significant amount of blood, greatly impairing his health. Father Kapaun would doggedly pick lice from prisoners who were unable to care for themselves.

He scrounged around, said Bill Funchess, visiting the various warehouses and stealing soybeans or other food for the other prisoners to eat. At great risk to himself, he would cross the barbed-wire fence to visit other compounds and help the men imprisoned there. He would lead prayers for both the Catholics and the non-Catholics. Lieutenant Funchess reiterated, as though reminding himself: “He did many good Christian-type things for the POWs, with no regard for their religious background.”

However, Father Kapaun’s health continued to deteriorate. When the priest was no longer able to walk, Lieut. Funchess cared for his wounded friend. Seeing his serious condition, Funchess offered him the choicest spot on the cold dirt floor, sleeping against the wall, so that no soldier stumbling through the total darkness of the hut to urinate in the night would mistakenly step on the priest’s injured leg. Funchess got all the prisoners to move over, to squeeze Fr. Kapaun into the safe spot near the wall. Then, with no warm clothing or blanket and no heat, Funchess rested against the priest on the coldest nights, helping to stave off frostbite and further illness. As the two men clung together for warmth, they did a lot of talking.

Funchess took it upon himself to perform an extraordinary act of kindness for Father Kapaun. When the weakened priest lost control of his bladder and bowels, it was Lieutenant Funchess who would scrub the soiled hut and wipe clean the gaunt body of his friend.

Finally, Funchess confided, one of the prisoners, on a walk through the camp, found what appeared to be the top half of a pot-belly stove. “It would be a fine toilet for Father Kapaun,” the soldiers thought; and Funchess applied the skill he’d learned from Fr. Kapaun, fashioning a rudimentary bucket of tin to fit beneath the seat. After that, the prisoners in his hut would assist Father Kapaun in getting to the toilet; and Lieutenant Funchess would carry the bucket outside for emptying.

Their time together was short. In the second or third week of May 1951, Chinese officers and guards burst into the hut and dragged Father Kapaun out. They were, they said in broken English, taking him to the “hospital”—or to what prisoners more realistically called the “death camp”, since most of the prisoners who were taken there never left to rejoin their fellow prisoners. Lieutenant Funchess recalled only two prisoners who had survived and came out of the hospital.

Funchess pleaded with the guards to leave Father Kapaun in the room where he was. He was in no condition to be moved. Other POWs, especially the Catholics, came running and tried to intervene. They were almost physical—pushing, shoving the Chinese guards and the Chinese English-speaking officer. The guards, though, were determined to take him—probably, Funchess thought, because they intended to take him to the ersatz “hospital” and allow him to die.

Funchess recalled that the guards permitted five or six Catholic POWs to take Father Kapaun out of his room and up the path to the so-called “hospital.” Once at the hospital, the guards closed the doors and sent the POWs back to their camp.

[The New York Times, reporting on the same story, reported that Father Kapaun had suffered from a blood clot, dysentery and then pneumonia, and in May 1951, guards sent him into isolation, without food or water, to die.]

There was no word for several days; finally, they got the word that Kapaun had died on May 23, 1951. Lieutenant Funchess didn’t know whether the earth had warmed sufficiently to allow a burial, or whether Kapaun’s body had been unceremoniously dumped in a heap, awaiting warmer weather.

* * * *

The Story Goes On

Some time later, after he was transferred to North Korea’s Camp #2, Funchess saw the five- or six-year-old daughter of the Chinese commander playing with a set of gold “cups” which had once belonged to Father Kapaun. Nothing in his Methodist faith had prepared Funchess to understand the purpose of the “gold cups”; but most likely, the little girl had acquired the priest’s military mass kit—and the cups were the chalice, ciborium and paten used in the liturgy.

* * * *

Lieutenant Funchess told me about another prisoner of war, a Jewish prisoner by the name of Jerry Fink. Fink, a Chicago native who had been trained as a military pilot, had been shot down on his first mission; and Fink and Funchess had spent a week together in “the hole,” an underground cell in the prison camp. Fink obtained rough wood from the woodpile, and used it to carve a crucifix for Father Kapaun.

Funchess, too, contributed to Father Kapaun’s crucifix. He had climbed to the rafters in a camp building and found a pair of tinsnips, which he used to cut the barbed wire. From the snipped wire, Funchess had fashioned a crown of thorns for the crucified Christ.

The crucifix, which is 24 to 26 inches high and perhaps 12”-15” across, was brought out of the camp by Catholic POWs when they were released at the end of the war. It is now enshrined at St. John Nepomucene Church in Pilsen, Kansas.

* * * *

On April 11, 2013, nearly sixty-two years after his death, Rev. Emil J. Kapaun was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Obama in an East Room ceremony in the White House. Receiving the Award was Father Kapaun’s nephew. The President, in presenting the award, said,

“This is an amazing story. Father Kapaun has been called a shepherd in combat boots. His fellow soldiers who felt his grace and his mercy called him a saint, a blessing from God. Today, we bestow another title on him — recipient of our nation’s highest military decoration.

“I know one of Father Kapaun’s comrades spoke for a lot of folks here when he said, ‘It’s about time.’ ”

* * * *

The Diocese of Wichita and the Vatican have begun the formal process that could lead to Father Kapaun’s canonization. In 1993, it was announced that Fr. Kapaun would receive the title of “Servant of God”.

PRAYER TO FATHER KAPAUN

Lord Jesus, in the midst of the folly of war,

your servant, Chaplain Emil Kapaun spent himself

in total service to you on the battlefields and

in the prison camps of Korea, until his

death at the hands of his captors.We now ask you, Lord Jesus, if it be your will,

to make known to all the world the holiness

of Chaplain Kapaun and the glory of his

complete sacrifice for you by signs of

miracles and peace.In your name, Lord, we ask, for you are the

source of peace, the strength of our

service to others, and our final hope.Amen

Chaplain Kapaun, pray for us.