It was Patriarch Bartholomew who broke the news: On his return from Jerusalem, where the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople had prayed with Pope Francis at the Holy Sepulchre, the Patriarch revealed plans for a Catholic-Orthodox get-together in Nicaea in 2025.

The meeting in Jerusalem of the Roman Catholic pontiff and the leader of the Eastern church was news in itself: It had been 50 years since the 1964 embrace between Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras. Before that, nine centuries of silence had separated the East and the Christian West, despite their shared belief in the sacraments and apostolic succession.

To be clear, the meeting planned for Nicaea is not actually an “ecumenical council.” An ecumenical council is one which brings together all the Christian churches of the world to discuss theological issues and seek consensus. Rather, the 2025 meeting in Nicaea (now called Iznik, 80 miles southeast of Istanbul) is planned as a “joint commemoration” of the earlier council.

And it need not be Pope Francis and Patriarch Bartholomew who preside at the historic meeting. Francis is 76, and Bartholomew is 74; in ten years, either or both may have passed the reins to their successors.

Vatican Insider reported on Patriarch Bartholomew’s remarks during an interview with AsiaNews:

Speaking to AsiaNews, missionary agency, Bartholomew said that along with Pope Francis “we agreed to leave as a legacy to ourselves and to our successors to meet in Nicaea in 2025, to celebrate all together, after 17 centuries, the first Synod really ecumenical, where he was issued the Creed.

“The dialogue for unity between Catholics and Orthodox…in this city, in the autumn, there will be a meeting of the Catholic-Orthodox Joint Commission, hosted by the greek-orthodox patriarch Theophilos III…. a long journey in which all must commit without hypocrisy.

“Jerusalem–the place, the land of the dialogue between God and man, the place where is the incarnate Logos of God, our predecessors Paul VI and Athenagoras have chosen this place to break a silence that lasted centuries between the two sister Churches.

“I walked with my brother Francis in the Holy Land with no fears of Luke and Cleopas on their way to Emmaus (cf. Luke 24: 13-35), but inspired by hope alive, as we learn from our Lord.”

The meeting does, though, bring back to life the hope for eventual reunion. There will be plenty of opportunity for the Catholic and Orthodox churches to work together toward that goal in the ten years leading up to the 2025 meeting.

* * * * *

What Is an Ecumenical Council? And What Happened in Nicaea I and II?

NICAEA I

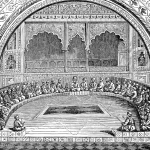

The first of the ecumenical councils, Nicaea (325 A.D.), became a model for many that followed.

- It was ecumenical in the sense that bishops were summoned from the whole inhabited world; and

- It was ecumenical in the more traditional sense that its decisions were meant to be binding on all Christians, and not merely on those of this or that diocese or patriarchate.

It was called in the face of the special crisis arising from the spread of the Arian heresy. (Arius believed and taught that the Son is not of the same substance as the Father, but was created as an agent for creating the world.)

It was conducted by means of a free debate, but when the decisions were reached (e.g., to define Jesus Christ as “true God of true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father”), the bishops who were recalcitrant were subject to ecclesiastical excommunication and political exile.

The Council of Nicaea, perhaps more than any other, is an event of highest importance in the history of Christianity. For the young church of the time, the Emperor Constantine’s support of the Christian faith was urgently welcomed. Constantine had seen the Christian faith survive many persecutions, and even before his conversion, he sought to establish a positive relationship between Christianity and the Roman state. When internal disputes (such as the Donatist schism in the west, and the Arian struggle in the east) threatened the Church, Constantine asked the bishops representing the whole church of the empire to meet and resolve their conflicts peaceably.

Where Was the Council? – The site chosen for this meeting was Nicaea in Bithynia, a town near the emperor’s summer home of Nicomedia. Another advantage to Nicaea was that located near the sea, it was within easy reach of the oriental bishops.

When Was It Held? – This first general synod lasted from May 20 to July 25, 325 A.D.

Who Attended the Council? – Because the church had, by this time, spread great distances, few western bishops were represented at Nicaea. The theologian Hosius, bishop of Cordova, was present. The three most important bishoprics of the east (Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem) were represented. Eusebius, bishop of Nicomedia, was an important voice at the Council. Caesarea the historian, with a large number of others from the east, were in attendance. And Athanasius, who would later succeed Alexander as bishop of Alexandria, was present and played a prominent role arguing against Arius.

A Model for the Future – The Council of Nicaea proved to be the model for many that followed. Church officials, recognizing the danger of emerging heresies and divergent teachings, recognized that they must speak with one voice; and Nicaea established the authority of the pope and bishops to define Church teaching. The Council was conducted by means of a free debate; but once decisions were reached (such as the definition of Jesus which appears in the Nicene Creed, as “true God of true God, begotten not made, consubstantial with the Father”), bishops who continued to dispute the Council’s decision were subjected to ecclesiastical excommunication and political exile. And although the emperor played a major role (funding the sessions, convening the sessions, and punishing recalcitrants), it was understood that the emperor acted only with the consent of the bishops and, most especially, with the consent of Pope Sylvester.

Major Decisions: The Nicene Creed – The primary focus of the Nicaean Council was on the Arian question, dealing with the relationship of Christ to God. Before Nicaea, only a small minority of believers adhered strongly to Arius’ view of the Son as a created being, and only a few adhered strongly to the opposing view of Alexander. Most of Christendom, then, fell somewhere in between–able to define what they did not believe, but stopping short of firmly stating just what they did believe. It remained the role of the Nicaean Council to define the position which would become the official doctrine of the Church.

The first creed to be brought before the Nicaean Council was an Arian statement of faith. This Arian position was met with a storm of indignation and hostility from a majority of the participants; and it appeared evident that it could not find acceptance. A second creed was introduced by Eusebius of Caesarea, who submitted the baptismal creed of his community. However Eusebius’ creed actually predated the controversy which Arius had introduced. Although Eusebius’ creed might have won easy acceptance and avoided controversy, Constantine recognized that eluding the difficulties in this way would not shield against future disputes. Therefore, he insisted that the Council continue its deliberations, and develop a Creed which could be generally accepted.

Constantine himself proposed an effective compromise: He recommended that the Caesarian creed should be modified by the inclusion of the Alexandrine words (including the term “identical nature”). His proposed model more clearly defined certain understandings of the faith, while deleting certain portions which were likely to fan the flames of controversy.

The Nicene Creed was the first dogmatic definition of the Christian Church, and has stood until the present time as a model for orthodoxy. Almost all of its expressions are drawn from the scriptures, with the addition of certain philosophical terms. In the Nicene Creed, the meaning of Scripture is made clear in the light of Tradition. The Son’s divinity is defined.

Continuing Struggle – The new Creed was not, as Constantine had hoped, the beginning of an age of harmony and peaceful coexistence. Rather than promoting peace, the Nicene Creed opened the eyes of many bishops to the significance of the problem it addressed. The Church faced its most serious challenge, with many bishops and faithful facing excommunication, rather than embracing the tenets laid before them.

The Easter Question – At the time of the Nicaean Council, there was agreement among Christians that Easter, the celebration of the Resurrection of Christ, was a day of great importance to the Church. However, observance of important Church feasts was not yet standardized by official action. The Nicaean Council decreed that (1) all Christians should observe Easter on the same day; (2) Jewish customs should not be followed; and (3) the practice of the West, of Egypt, and of other Churches should remain in force–namely, that of celebrating Easter on the Sunday following the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

Other Issues – While the Arian heresy has remained a focal point for study of Nicaea, the Council addressed 20 other disciplinary matters, such as the “lapsed” in the recent persecution, the question of “heretical baptism,” and diocesan organization. Several canons had to do with the dignity of the clergy: the rank order of bishops, priests and deacons, a well as the ordination of eunuchs, of those insufficiently tested since Baptism or proved unworthy, of those who have denied the faith in persecution, and cohabitation of clerics with other than relatives or women beyond suspicion. Canon 13 confirms the ancient practice of giving Communion to penitents at the hour of death.

Nicaea established a twofold criterion for the admission of heretics: those who have not erred on the doctrine of the Trinity were to be reconciled without repetition of their Baptism; while those who did not confess the Trinity remained unreconciled to the Church.

And a purely practical matter: On Sundays and the days of Pentecost, the faithful were to stand for reading of the liturgy, not kneel.

* * * * *

THE SEVENTH COUNCIL: NICAEA II

The seventh ecumenical council, and the last to be recognized by the Eastern Church, lasted from August to October 787.

At that time, the practice of venerating images had been forbidden in Byzantium for more than a century and a half, and it seemed unlikely that this policy would change. Emperor Constantine V and his successors were iconoclasts–persons committed to the destruction of religious images and opposed to their veneration. But when Empress Irene assumed power in 780 in the name of her son, Constantine VI (who was still a minor), she was determined to restore the veneration of icons. She plotted to get rid of her opponents in the government, then contacted Pope Adrian I, requesting that he establish a council to consider the matter.

Of the eight sessions at Nicaea II, seven were held at the church of Hagia Sophia in Nicaea. Patriarch Tarasius presided over the sessions, but the papal legates in attendance signed all the documents first, and were always listed first.

The first three sessions considered whether the iconoclastic bishops could be seated at the council. Despite open opposition from the monks, the iconoclasts were seated on the Council once they had renounced their iconoclast position and had been reconciled with the Church. The next issue was establishing the legitimacy of veneration of icons–which was accomplished by means of an examination of scripture and tradition. The sixth session was called to review and then reject Rome’s demand that the great synod held at Hiereia in 754 be condemned. The seventh session of the Council finalized Church dogma concerning intercession of the saints, and legitimacy of the veneration of icons or statues. It highlighted the differences between veneration of saints, and the highest adoration which is reserved for God alone.

Nicaea II, then, marked the end of the first period of iconoclasm.