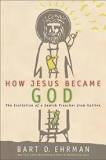

Author: Bart D. Ehrman, professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Title: How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee

Publisher and Date: HarperOne, 2014. Page length: 404 pp.

All Scripture references are from the NRSV unless otherwise noted.

Part 1

Dr. Bart Ehrman is probably the most successful author of theological books in America. He has five New York Times bestsellers including this one, How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. Ehrman is a lucid writer who is easy to read. Thus, several of his books are trade books.

Dr. Bart Ehrman is probably the most successful author of theological books in America. He has five New York Times bestsellers including this one, How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. Ehrman is a lucid writer who is easy to read. Thus, several of his books are trade books.

There is so much in this book by Dr. Ehrman that I want to address. So, this review will be lengthy, thus in three parts, for two reasons. First, this book is an important effort to refute the good news about Jesus. Second, I wrote a 600-page book on this subject–whether or not Jesus is God. It is titled The Restitution of Jesus Christ. It is much more thorough regarding Scripture than Ehrman’s book, and I cite over 400 scholars in it. Ehrman doesn’t cite many scholars because his is a trade book–being for general readers. Ehrman and I agree that Jesus never thought he was God or claimed to be God, but that’s about all we agree about on the subject of Jesus’ identity and his mission.

Bart Ehrman and I are members of the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL). I first met him at SBL’s Annual Meeting in 2010. In 2008, I had self-published my RJC book anonymously under the pseudonym Servetus the Evangelical. Right before meeting Dr. Ehrman I had publicly revealed myself as the author of this book. So, I told Bart briefly about it and asked if I could send him a copy. He gave me his card and said I could. But he added that he likely would not have time to look at it. I lost his card and didn’t bother to get his address and send it to him. Little did I know that about this time he had decided that he was going to write this book, How Jesus Became God. My book biblically challenges the post-apostolic church dogma that Jesus is God while affirming every other major church teaching about Jesus.

The Annual Meeting of SBL is always the weekend before Thanksgiving. At the 2014 meeting, I attended a 2.5 hour session in which six panelists critiqued this book, How Jesus Became God, and Ehrman was present, responding. The panelists were David Capes, James McGrath, Michael Bird, Dale Martin, Craig Evans, and Larry Hurtado. During the intermission, I told Ehrman I wished I had sent him my book.

The Annual Meeting of SBL is always the weekend before Thanksgiving. At the 2014 meeting, I attended a 2.5 hour session in which six panelists critiqued this book, How Jesus Became God, and Ehrman was present, responding. The panelists were David Capes, James McGrath, Michael Bird, Dale Martin, Craig Evans, and Larry Hurtado. During the intermission, I told Ehrman I wished I had sent him my book.

Dr. Bart Ehrman is a historian who is professedly agnostic, yet he is a professor of the New Testament and Early Christianity. This scenario is not so strange anymore since American secular education now realizes the importance of the Bible for a fully-rounded education in the humanities.

Dr. Ehrman writes in this book about having been an evangelical Christian in his teens. He graduated from the fundamentalist Moody Bible Institute. While getting his PhD (1985) at Princeton Seminary, he says (p. 86), “I had begun to entertain doubts about some of the most fundamental aspects of the faith, including the question of the divinity of Jesus. During those intervening years I had come to realized that Jesus is hardly ever, if at all, explicitly called God in the New Testament … only in the Gospel of John.”

Ehrman begins his Introduction by saying (p. 3), “The idea that Jesus is God … was the view of the very earliest Christians soon after Jesus’s death.” I strongly disagree. I show in 322 pages in my RJC book that nowhere does the NT declare that Jesus is God, and I treat the critical biblical texts in depth. Ehrman further surmises (p. 6) “how Jesus came to be considered God. The short answer is that it all had to do with his follower’s belief that he had been raised from the dead.” WOW!

This is the thesis of Ehrman’s book, How Jesus Became God. Some Christians have also believed this. But it is irrational and antithetical to Judaism. Thus, it is highly unlikely that the early Jewish Christians believed that. Tom (N.T.) Wright and other leading NT scholars have convincingly refuted this argument. Most Jews during Jesus’ time, including him and his contemporaries, the Pharisees and Essenes, believed in the future resurrection of God’s people, and they certainly did not think that would make them gods.

On April 7, 2014, National Public Radio (NPR) published an online interview with Dr. Bart Erhman about How Jesus Became God. Here is an excerpt from Ehrman’s remarks in this interview:

During his lifetime, Jesus himself didn’t call himself God and didn’t consider himself God, and … none of his disciples had any inkling at all that he was God. …

During his lifetime, Jesus himself didn’t call himself God and didn’t consider himself God, and … none of his disciples had any inkling at all that he was God.

You do find Jesus calling himself God in the, or the last Gospel. Jesus says things like, “Before Abraham was, I am.” And, “I and the Father are one,” and, “If you’ve seen me, you’ve seen the Father.” These are all statements you find only in the Gospel of John, and that’s striking because we have earlier gospels and we have the writings of Paul, and in none of them is there any indication that Jesus said such things.

I think it’s completely implausible that Matthew, Mark and Luke would not mention that Jesus called himself God if that’s what he was declaring about himself. That would be a rather important point to make. This is not an unusual view amongst scholars; it’s simply the view that the Gospel of John is providing a theological understanding of Jesus that is not what was historically accurate.

This is indeed what Ehrman says in this book. Thus, he takes the typical position of historical-critical scholars about Jesus and the NT gospels. They correctly state that, according to the synoptic gospels, Jesus did not believe he was God or say he was God, and his early disciples didn’t believe he was God either. But Ehrman errs in saying the Gospel of John identifies Jesus as God. (See pp. 124-25, 248). About Ehrmans’ quotes of Jesus in John 8.58, Jesus therein didn’t mean he preexisted but that he was superior to Abraham. The prior context of John 10.30 shows that Jesus meant he and the Father work together in unity as “one,” not that they are one in essence as some church fathers asserted. (Cf. “one” in John 17.11, 22-23). And Jesus saying, “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14.9), does not mean he is God or the Father since he then explained it to mean, “I am in the Father and the Father is in me” (v. 11; cf. 10.38). Scholars call this the Mutual Indwellling, and many people have confused it with Jesus being identified as God. Yet Ehrman is right in saying that if Jesus publicly said he was God, Matthew, Mark, and Luke would have mentioned it in their gospels. Moreover, Jews would have argued with him about it far more than that he was the Messiah. Ehrman rightly says later that being a Jew (p. 98), “Jesus would have believed that there was one true God.”

As stated above, Ehrman says that right after Jesus’ death, the early Jewish Christians began to believe that Jesus was God. On the contrary, I maintain that the NT does not say Jesus was God, so that it was not until the second century, after the apostolic era and the writing of the NT, that some Christians began to say Jesus was/is God. But for the next two centuries they said his divinity/deity was less than that of the Father, making Jesus essentially subordinate to God. It was not until the Nicene Creed, in 325, that Christians declared Jesus is God just as much as the Father is. And only in the latter half of the fourth century did Catholic Church officials construct the doctrine of the Trinity that we know about today.

(Many Christians, theologians, and historians wrongly claim that the doctrine of the Trinity was established at the Nicene Council. It’s because the creed often recited in churches is said to be the Nicene Creed, whereas it is the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 that is almost always recited. It is a modification of the Nicene Creed, and part of that modification is that it includes the Trinity teaching.)

In Chapter 1, Ehrman gives mythological examples in the Hellenistic world during the early Christian era of men being divinized and gods becoming men to rightly show that this environment made it easier for Gentile Christians to think of Jesus as God. Bart well states (p. 43), “How could Jesus be God and God be God and yet there be only one God? That, in part, is the question that drives this book.”

In Chapter 2, Ehrman says again of early Christians (p. 49-50), “How could they say that Jesus was God and still claim that there was only one God. If God was God and Jesus was God, doesn’t that make two Gods?” Indeed. And I am surprised Ehrman fails to mention that both the Ebonite and Nazarene sects of early Jewish Christians lodged this argument. It was Gentile Christians in the next century, such as Ignatius, who started saying Jesus is God. When they did, critics accused them of believing in two gods. But Ehrman says (p. 49) that he was enlightened to learn that “Christians were calling Jesus God” in “competition” with “the Romans calling the emperor God.” Maybe in the second century, but not the first century as Ehrman claims.

Then Mr. Ehrman takes the same line as traditionalists Larry Hurtado and Richard Bauckham. They say there were Jews in the Second Temple period who believed the souls of men could ascend to heaven and return with secret knowledge or men themselves could become angels or divine. (I refer to Christians who believe Jesus is God as “traditionalists.”) Indeed there were, but rabbis have always said they were on the fringe and thus not in mainstream Judaism. Heh, “two Jews, three opinions.”

Ehrman says (p. 61), “Larry Hurtado states a key thesis: ‘I propose the view that the principal angel speculation and other types of divine agency thinking … provided the earliest Christians with a basic scheme for accommodating the resurrected Christ next to God without having to depart from their monotheistic tradition.’” I don’t think that is stated properly. Larry means “Christ next to God as his equal.” I certainly believe Jesus sits next to God on his throne in heaven. In my RJC book, I oppose what Larry means here and cite him about it. I discussed this with him when he was our keynote speaker at the Kermit Zarley Lectures at North Park University in 2008. Years later I sent him my book, but never heard from him.

In Chapter 3, Ehrman errs like so many NT scholars, including some Christian scholars, by alleging (p. 102, 105), “Jesus is portrayed in our earliest Gospels, the Synoptics, as being an apocalypticist anticipating the imminent end of the age … within in his own generation before his disciples had all died, what was one to think a generation later when in fact it had not arrived? One might conclude that Jesus was wrong.” Jesus was indeed an apocalypticist. But Matthew 24.36/Mark 13.32 show that he did not know when he would return, so that he could not have believed that it would be soon. I have an unpublished book manuscript in my STILL HERE series about this subject.

Although it is not part of Ehrman’s thesis, like other scholars he wrongly asserts (p. 118), “Jesus did not think that the future kingdom was going to be won by a political struggle or a military engagement per se.” On the contrary, the Old Testament says the Messiah will militarily deliver Israel from extinction at the end of days (e.g., Isaiah 9.1-6; 11.1-4; cf. Isaiah 63.1-6 with Revelation 14.20; 19.15; Micah 4.11—5.5). Orthodox Jews have always rightly believed this. It’s just that Jesus will do this at his second coming. My STILL HERE book, Warrior from Heaven, is all about this subject.