Hurricane Harvey slammed into the Texas Gulf Coast last Friday with a knockout punch. Rated a #4 hurricane, which is next to the highest strength at #5, Harvey’s center made landfall at Rockfort, Texas, 225 miles southwest of Houston. The wind did much damage there.

Hurricane Harvey slammed into the Texas Gulf Coast last Friday with a knockout punch. Rated a #4 hurricane, which is next to the highest strength at #5, Harvey’s center made landfall at Rockfort, Texas, 225 miles southwest of Houston. The wind did much damage there.

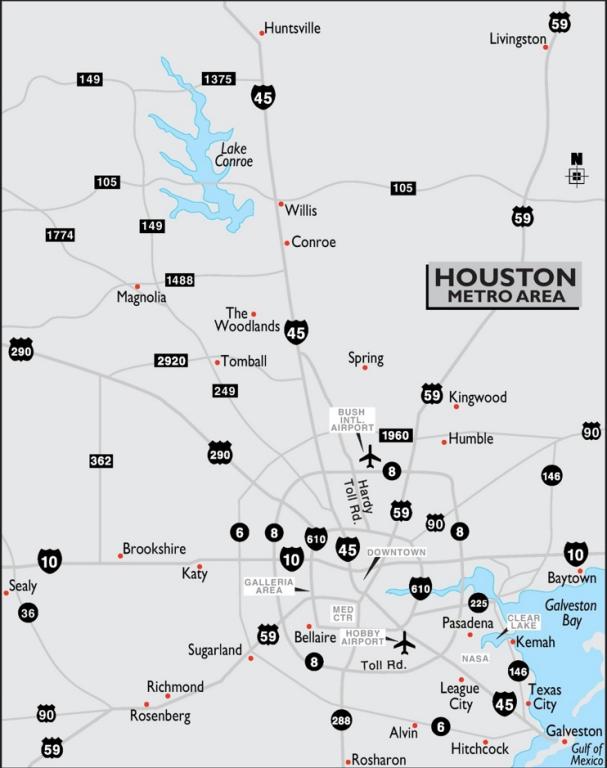

When hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico make U.S. landfall, they often move northeast. Harvey moved east a little, then returned back to the Gulf. Hurricanes gain strength from the water when they do that. Then Harvey made landfall again. It was soon downgraded in strength and relabeled a “tropical storm.” Harvey kept moving eastward, right toward Houston. Then it did the worst thing possible. Harvey stopped. Its wind kept blowing in a huge circle, but the storm itself quit moving much. That’s when a tropical storm can dump a mass of water. Harvey did just that over all of Houston, the sixth largest city in the U.S.

When weather officials downgrade a hurricane to a tropical storm, the word “downgrade” can be misunderstood. Officials only mean by it that the wind strength lessens. But the primary damage, and even loss of life, from hurricanes and tropical storms can be due to flooding more than wind damage. That’s what is now happening in Houston with Harvey.

I know something about this stuff from experience. I lived in metro-Houston for nearly forty years. In 1979, a tropical storm came off the Gulf Coast and stopped right where I lived, in Friendswood, a south suburb of Houston. The National Weather Service had a weather station in Alvin, seven miles southwest of Friendswood. On July 23-24, 1979, that weather station registered 43 inches of rainfall in only 24 hours. That has been the largest amount of rain ever measured in a populated area in the USA. But the total rainfall from that 1979 storm was about 45 inches. As I understand it, U.S. weather officials are now saying today that Hurricane Harvey has produced the most rainfall on U.S. land in modern history, going over 50 inches in some places.

I wasn’t home when this storm hit in 1979. My family and I were enjoying the week in the city of “brotherly love,” in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I was playing in the PGA Tour’s golf tournament there. When the water soon drained out of our Texas house, our dear church friends moved our furniture and carpets out of the house to dry off in the sun. Then they told us on the telephone that it wasn’t worth me withdrawing from the tournament and flying home. They said there wasn’t anything else I could do for several days. When you get flooded, you move the furniture and the carpets out of the house and just wait for days thereafter for everything to dry out, including the house.

Houston, Texas, is a flood-prone area due to its nearness to the Gulf of Mexico, its low elevation, and thus being subject to storms off the Gulf. Downtown Houston is located about 50 miles from the Gulf, and Friendswood is 25 miles away. Since Friendswood is located south-southeast of Houston, one mile off Interstate 45, it is slightly more prone to flooding.

When my wife and I purchased property and built a house on it, in 1970, we chose that lot expecting it could never flood. So, I didn’t even bother to buy the government-subsidized flood insurance for the house, which was only something like $200-300 per year. That was one of the stupidest financial decisions I’ve ever made.

About 15,000 homes flooded in that 1979 tropical storm. Our single-story house, with no basement, flooded 18 inches. In restoring a flooded house, owners have to decide whether or not to remove all of the inside sheetrock and wall insulation. The main reason is not aesthetics; rather, its mold that will grow in the future, both on the sheetrock and the insulation. We made a good in cutting out the sheetrock three feet up from the floor and removing the insulation. It was a lot of work, but it had to be done. All five members of my family had allergies, and there’s nothing worse for allergic people than mold. And since southeast Texas is such a humid climate, where mold thrives, that was all the more reason why we had to do all we could to avoid mold. Some of those 15,000 homeowners didn’t do this, and they suffered for it.

For the next year or so in our area of south Houston and thereabouts, people walked around with the saddest faces. It was depressing. There was so much work to do to restore all those flood damaged homes. Even getting carpenters to help could be difficult, since there was so much work available and not enough workers. Then too, some of the workers weren’t skilled at certain crafts even though they took the work.

After that experience, I often thought of living somewhere else, where there aren’t any hurricanes and tropical storms to do you in. Two decades later, I wound up in Arizona. The desert heat here can be stifling. But it’s nothing compared to those Gulf of Mexico storms. I’m glad I have no more of that. But I sympathize with the many, many people in southeast Texas and even next door in Louisiana who will be suffering from the results of Hellacious Hurricane Harvey for many months, if not years, to come.