Last night Marisa and Carson Calderwood were excommunicated at a Church Discipline held at their Maple Valley, Washington stake.

Last night Marisa and Carson Calderwood were excommunicated at a Church Discipline held at their Maple Valley, Washington stake.

Marisa and Carson are cradle Mormons who had done everything they were required to do; missions, temple marriage, children, church service.

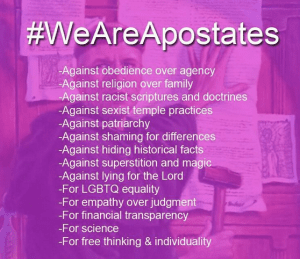

Their sin? They talked to people about their thought, their questions and their doubt. For that they have been dubbed ‘APOSTATE’ and expelled.

This sort of stuff always sends up a cheer from the certain and the unquestioningly embedded. As it might. I’ve long realised that its really their church and they simply don’t want those with questions on their pews. I accept that for many I’m just a turn coat and an interloper with cautions written all over my Sunday best but I had always hoped for something more from my faith community writ large. Even if it was a tiny bit more. This morning I feel like it was a mistaken hope. In truth there is little hope of a renaissance or reformation or an intellectual flowering. There is little hope for inclusivity, diversity, and rigorous questioning, because – let’s face it – that’s not Mormonism.

Mormonism is patriarchal to its roots. Mormonism is an exclusivist, American imperialist, conservative, exceptionalist, millenialist, polygamist, militarist, corporatist, extreme oligarchy. That’s what it is – and it has no intention of being anything other than this, at least while its also racked with fear, and what a fearful, fearful community it is at present – shamefully so. And I have to wonder if a thoughtful faith is ever going to be possible, because of the fear it arouses;

“Men fear thought as they fear nothing else on earth — more than ruin, more even than death. Thought is subversive and revolutionary, destructive and terrible, thought is merciless to privilege, established institutions, and comfortable habits; thought is anarchic and lawless, indifferent to authority, careless of the well-tried wisdom of the ages. Thought looks into the pit of hell and is not afraid … Thought is great and swift and free, the light of the world, and the chief glory of man.” (Bertrand Russell)

That being said – I would still like to raise my objection to excommunication – as I have done frequently. I don’t sustain it – and here’s why;

Excommunication in the LDS church is a strange American frontier bricolage, partly constituted as a 19th century legacy from Joseph Smith’s habit of excommunicating and re-baptizing all in the same week; partly an institutional form appropriated from the threads of other religious traditions; and partly a way of working out and responding to spontaneously occurring challenges to local authority. It has far too many of all kinds of religious discourses embedded into both its rationale and its execution and not enough care or thought into its management or its scope. It is all axe to the tree and not enough law and governance. There is too much judgment and not enough grace. Final decisions are made by too many spiritual generalists and not enough religious specialists.

Mormon moral arbitration is a strange esoteric business involving more than the presentation and weighing of evidence. A supernatural, metaphysical and discarnate subjectivity is deployed in church disciplines in order to reach the final determination of either guilt or innocence – with a heavy emphasis placed on the ‘damage to the church’. Excommunication is a brutal practice in Mormonism that seems to make up its rules and declares its judgments as a matter of ‘intuition’, ‘revelation’ and ‘spiritual promptings’ which can be as subjective, variable, and as flawed as deciding what to have for dinner. There is simply too little in the way of regulation, study, context and intellectual work around the practice of excommunication from the LDS church to render me satisfied with its efficacy.

Inasmuch as we have borrowed this practice from the Catholics it might also be instructive to point out that at the Council of Trent, ending in 1563, decided jointly that excommunication carries with it its own social and spiritual evils on account of the excessive and punitive use of the practice 500 years ago. In this case it was agreed that:

“Although the sword of excommunication is the very sinews of ecclesiastical discipline, and very salutary for keeping the people to the observance of their duty, yet it is to be used with sobriety and great circumspection; seeing that experience teaches that if it be wielded rashly or for slight causes, it is more despised than feared, and works more evil than good.”

And what is its primary evil?

With every excommunication there is loss. With every expulsion and punitive action against thoughtful people an organisation loses its power to grow in spirit and to be better as a community. It loses its capacity to dialogue and to work out difficult theological and religious dilemmas. It loses its moral authority to create positive social change and to influence the world to take on hard issues with spiritual insight. With every excommunication the capacity for deeper and more meaningful engagements with questions of the spirit, and who Jesus was, and what our role as a community who loves God is lost.

With every single excommunication you excommunicate in spirit thousands of people who yesterday wondered if they belonged, and this morning have accepted that they probably don’t.