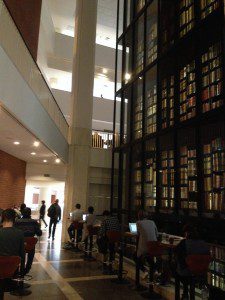

My heart knocked against my ribs as I took the stairs two at a time. “The library will be closing at 8 o’clock,” announced a crisp voice over the loudspeaker, though the area of London I was in is one of the least nominally English. Bearded men and women in hijabs speaking Urdu and Arabic outnumbered most of the other shoppers on the adjoining high street, a circumstance central to my mission. If anywhere, I thought, this particular library would have what I was looking for. But I didn’t have much time to find out. Almost out of breath, I ran up to the third floor and scanned the Religion section. There – the shelf labeled Islam. When I looked over the titles, his name leapt out at me as though it were written in fire: Muhammad.

Even in my mind I still had trouble saying it. But it wasn’t just a matter of using the correct pronunciation, which puts a swell in the “h”, and presses both “m”s to your lips like a long sigh. It also felt a little dangerous to me, like I would be giving something away. When I say the name of someone I have feelings for, you can hear it in my voice.

Which was my secret reason for coming to the library. I’d read a few books about Muhammad already, but they only traced the trajectory of his life story: from being an orphan and an outsider in Mecca to receiving the revelation of the Qur’an in mid-life and becoming the leader of a new community in Medina. None of them answered the most important question of all, at least as far as I was concerned: was it ok to fall in love with him?

I worried it might be one of those new-convert faux-pas that I only became aware of once someone started yelling at me. Just a few days before, I’d gone to Regent’s Park Mosque in central London for the first time, and had an older auntie make a beeline for me when I entered the ladies’ prayer area. After demanding to know if I was Muslim, she shrilled: “You need to be covered!” I looked down at what I was wearing: a shirtdress over jeans with a long-sleeved cardigan and socks still damp from my ablutions. Of course I was also wearing a headscarf. The only visible areas of skin were my hands and my face. Wondering how much more covered I needed to be, I looked back up to see her brandishing a raincoat that could have wound around me three times over.

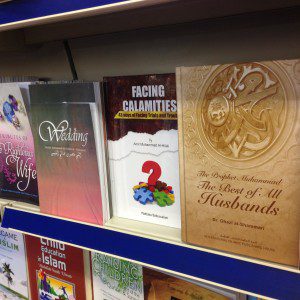

I declined the extra wrapping. But after the prayer, when I went into the mosque bookstore, I was arrested by all the different titles in the Women & Family section explaining what a good sister should be. Not only was there a dress code, but also numerous and detailed manuals of behavior, such as The Ideal Muslimah: The True Islamic Personality of the Muslim Woman as Defined in the Qur’an and Sunnah along with The Encyclopedia of Islamic Jurisprudence Concerning Women (a three-volume set). It made me wonder whether Raincoat Auntie had been right; whether feeling like I was covered meant I actually was – or not.

I had a similar debate with myself as I stood in the stacks of the library. Reflecting on Muhammad’s kindness and strength of character, his dazzling smile, soft beard, and broad chest, not to mention the fact that everyone said he always smelled so nice, I could feel myself getting googly-eyed and full of butterflies all over again. But was I doing something inappropriate without realizing it, just by having feelings for the Prophet? Would someone better versed in matters of Islamic jurisprudence tell me it was makruh, a disliked action like sleeping late, or mubah, permissible but not really recommended?

Part of me wanted to be told it was haram, forbidden, and that I must put a stop to such feelings straight away. But not only because I was afraid of making a religious mistake. The truth was, I’d been using spirituality as an escape route. And the thing I wanted to escape most from was love.

Following my divorce five years earlier, I had sworn off relationships. I cut my hair as short as a monk’s and got serious about meditation. Determined to free myself from the suffering wrought by desire, I resolved that I would not get attached, I would not get entangled, and I most definitely would not get into any kind of situation involving the heart. My heart was like a bad part of town I was trying to avoid, a dark alley where I’d gotten mugged. No way I’m going back there again, I thought: I’m going to stay safe this time.

However, it wasn’t long before my spiritual path took me in a new direction, to Sufism. My introduction came through Rumi. Verses like, “The moment I heard my first love story, I started searching for You,” are definitely love poems, whether you read them as love poems addressed to another person or as love poems to Allah, the Beloved with a capital B. Yet I had elected to read Rumi’s poetry as literature, appreciating the beauty of the sentiment while leaving it confined to words on the page. I didn’t mind talking about love, as we did so often and so extensively in the Mevlevi Sufi circle I joined, as long as I didn’t have to feel anything.

But that proved a challenge. Each element of our practice seemed to awaken a different part of me: from the touch of the softly tufted sheepskins we prostrated on in salaat to the long hugs shared with my fellow sisters after the prayer; from the resinous incense that perfumed our gatherings to the melancholy notes of the ney flute unfurling with the skirts of our whirling dervishes. The sweetness and longing I felt in these moments were no longer mental concepts or inert words on paper, but had become real feelings in my body.

At times I would be reminded of the Naqshbandi Sufi order’s practice of focusing their remembrance of God so intensively on their hearts that they start to beat visibly through their shirts. As I prayed and practiced, I also felt a sense of inner spaciousness expanding my chest.

And with that came room for new and different relationships in my life, including with the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). The more that I read and researched on his life, the more I realized that I did not want to know about him. I wanted to know the man himself: what cheered him and what challenged him, how he thought and what he felt. In a word, I wanted to be close to him.

Which brought me back to my old question: was it allowed to fall in love with the Messenger? I knew now I would not find the answer in a book. It could only be found in the repository of true knowledge that was my own heart. But it was not the dark alley that I feared. Instead, I knew my heart was the library I had been looking for all along.