One evening a few weeks before my 25th birthday, I alighted from a train in the Heidelberg railway station and took off running. It was a twice-weekly routine at the time. I was taking evening classes at the University of the Frankfurt, and the train returning me to Heidelberg arrived just a few minutes before the last tram of the night departed, leaving it up to me to make the short connection in a burst of sheer personal speed.

I am not a runner by inclination. Yet I managed to run fast enough to catch the tram every time. On the night in question, I caught it too. But as I sank into my seat on the tram afterward, I noticed that something felt strange about my knee. There was an odd kind of catch about it. It was almost as though, along with my heaving chest and pounding heart, my knee was out of breath too.

The next morning, the catch turned into a searing pain. I could neither bend nor fully straighten my knee. Upon going to the doctor, I learned I had torn my meniscus, an injury that was difficult to repair. I remember thinking to myself, with a mixture of panic and resignation: So. I’m officially getting old.

Almost two decades have passed since then. Now, thanks to my spiritual practice, I feel younger at age 43 in some ways than I did at 25. I am less critical, certainly, and also more optimistic, but it’s my feeling toward the aging body that has probably undergone the most dramatic shift.

Rumi says:

The spiritual path wrecks the body

and afterwards restores it to health.

It demolishes the house to unearth the treasure,

and with that treasure rebuilds it better than before.

Before I came to Sufism, I was involved in spiritual traditions where the awareness of impermanence and loss were important components of understanding the true nature of things. Meditation, in this view, was practicing how to die. “Live life with death as your advisor,” one of my teachers counseled explicitly.

The benefits of those teachings have been many and manifold in my life. I have been able to reach out and tell those dear to me that I love them, for example, and in some cases heal estranged relationships while there is still time to enjoy the renewed connection. But living with an awareness of mortality has been even more valuable in my relationship with my embodied self, especially given the denial of aging and death that prevails in our culture.

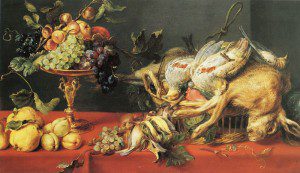

Until the modern era, the memento mori was part of the Western tradition. Living people might have their portrait painted with their hand resting on a skull. Still life paintings often included dead game or rotting fruit. Those images delivered a specific message that everyone understood: Remember you must die.

For me, momento mori are also those unexpected moments when I glimpse my own mortality. Going into a dressing room to try on clothes and instead noticing a new hollowness to my cheeks. Discovering freckles that have blurred into age spots. Observing certain pains arising, and persisting, while noticing that other functions of the body have become unreliable. Even my teeth do not seem to be set so solidly in my jaw anymore. Add to this the increasing incidence of random occurrences, like spells of dizziness or a heartbeat that hesitates, and the trend toward entropy is clear. Things fall apart, us included.

What is different for me now, on the Sufi path, is the sense that my own impermanence has a purpose. It’s the realization that all of the travails and troubles of aging – living in an ailing, failing body – are actually a gift in disguise, an instance of the Divine mercy.

Rumi says:

This world is like a tree,

and we are the half-ripe fruit upon it.

Unripe fruit clings tight to the branch

because, immature, it’s not ready for the palace.

When fruits become ripe, sweet and juicy,

then biting their lips, they loosen their hold.

When the mouth has been sweetened by felicity,

the kingdom of the world loses its appeal.

When the body is young, strong and healthy, the pleasures of the senses are so entirely pleasurable that they can become addictive. When the body itself becomes less comfortable to inhabit, however, its pleasures fade in proportion. I understand that process now as its own form of ripening. The spiritually mature soul can allow all of its former connections to worldly life and bodily pleasures to gradually drop away as it gathers its sweetness from within.

Despite knowing this, the process still isn’t always easy for me. I don’t like being in pain, and the increasing unpredictability of the body is hard to accept for a nafs that likes the illusion of being in control. But when I can be in Presence, and remember that the nature of the Divine is unconditional compassion and mercy, I can take the body’s failures as a series of gentle reminders. It’s as though Allah is whispering in my ear: “Dear one, your home is not in this body or in this world. You are only a traveler here, stopping over for a short time. Remember who you really are, and where you are journeying to. Don’t give your heart to impermanent things, because it will be lost when they pass away. Give your heart and soul to Me, and you will become truly alive in Life and Light.”

I am so grateful to be part of a tradition now that has its own memento mori tradition in literature. There are many beautiful verses by Mevlana both about spiritual ripening, as well as death as its own kind of birth, a transition into the next world. But on the subject of mortality, I want to give the last word to Yunus Emre, who says it better than anyone else:

Since this journey of Being began,

the Friend has rushed to meet us.Light has filled the ruins of this heart.

Let this universe of mine be shattered.I have passed up dreams.

I have tired of summers and winters.I have found the Gardener of flowers.

Let this garden of mine be dug up.Yunus, you say it well,

smooth as honey.I have found the honey of honeys.

Let this hive of mine be given away.