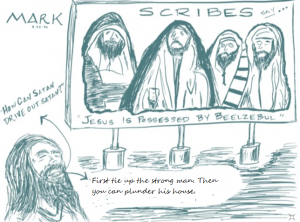

Name calling is a favorite tactic of challenged establishments. Today you might be called a communist or (heaven forbid!) a liberal. Here the establishment figures are scribes, and the insult of the day is Beelzebul. “By this prince of demons Jesus casts out devils.” In a subtle twist Jesus turns the charge around. Once again Jesus locates the spiritual realm (here the demonic) in real-life situations of Palestinian power. Ninth in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and a Table of Contents are HERE.

The last post saw the formation of what Ched Myers calls the “community of resistance.” Resistance against what? The next scene partly explains. (Mark 3:20-35)

Jesus goes “home.” We don’t know where that is, and that may be deliberate on Mark’s part. Crowds gather again, and two more conflicts arise, one of which we would expect but not the other. Mark puts these in the form of a sandwich to show that they are meant to illuminate each other. The conflict we expect is with scribes. This time they’re from Jerusalem, raising the tension in Mark’s story to a new level. On either side of this conflict Mark places a tension we don’t expect between Jesus and his “relatives” or “mother and brothers.”

The conflict we expect, the Beelzebul charge

A huge, boisterous crowd gathers around Jesus. Scribes who had come down from Jerusalem said, “He has Beelzebul, and by the ruler of the demons he casts out demons.” Jesus handily disposes of the charge.

Myers helps me see that Jesus is doing much more than claiming innocence. Jesus first lays bare the contradiction in the scribes’ claim: Why would Satan drive out Satan? But he doesn’t stop there. Next he talks about a kingdom which can’t stand if it’s divided against itself. Is he simply repeating the same thought in other words? But Jesus continues. Now it’s about a house that can’t stand if it’s divided against itself. Why would he say the same thing three times?

Myers explains. By end of Jesus’ triple broadside, the scribes are wondering if Jesus may be hitting close to home. He talks about a “kingdom” and a “house.” Maybe their own kingdom, the Davidic state, is under attack in these words. And maybe the “house divided” is the Temple, the house of God.

Jesus is not just reassuring the scribes, “No, I’m not on the devil’s side; where the devil is concerned, you and I can agree to agree.” Jesus’ “kingdom” and “house” hew uncomfortably close to the way the scribes think of Jerusalem’s centralized politics and religion.

Later Jesus will separate himself from David’s kingdom:

David himself calls [the Messiah] ‘Lord’; so how is he his son? (Mark 12:37)

He will also exorcise the Temple, throwing the sellers and buyers out (Mark 11:15-17). In the light of these later events, Myers thinks that Jesus is already here calling his opponents the devil’s agents. (Myers, pages 165-66)

If that’s true then the following passage has an ominous meaning which I never suspected:

No one can enter a strong man’s house to plunder his property unless he first ties up the strong man. Then he can plunder his house. (Mark 3:27)

You have to be stronger than the strong man to plunder his house, and Jesus is the “stronger one.” (Remember what John the Baptist said in 1:7.) Whose house is Jesus going to plunder? Remember the ones who don’t need a physician, the ones whom Jesus does not call as he calls the “sinners.” They are the strong, self-righteous ones, the very ones now trying to discredit Jesus. Jesus locates Beelzebul, the Satanic strong man, right in the middle of Jerusalem. He gives the scribes fair warning of the plundering he intends to do.

The conflict we didn’t expect.

Mark says Jesus is at home for this Beelzebul episode without telling us where that is. At any rate, that is where Jesus’ relatives have come. “Home” here may be symbolic of more than just a house where Jesus stays. Jesus’ “relatives” at the beginning of this section and his “mother and brothers” at the end are not able to enter this home. Ostensibly that’s because of the crowds, but it may be that the “home” is simply not theirs spiritually.

At the beginning his relatives are going to “seize” him, almost like a police action. They say, “He is out of his mind.” Jesus doesn’t find out that his mother and brothers are outside asking for him until the end of the scene. Then he says, looking at the folks surrounding him, “Here are my mother and my brothers. For whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.” Jesus is “at home” with his new brothers and sisters and mother.

Family values

In our age of many words honoring “family values,” it’s jarring to see how Jesus relates to his own family. No doubt family values are Christian values, but Jesus doesn’t often stick up for them. Sometimes he seems to do the opposite:

A prospective disciple asks leave to perform the essential family duty of burying a parent. Jesus says, “Let the dead bury their own dead.” (Luke 9:60)

Jesus says to a large crowd, “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple.” (Luke 14:26)

There’s more than one kind of family value. Myers says kinship “is the backbone of the very social order Jesus is struggling to overturn.” (Page 168) It’s the seat of not only personality and identity but also socialization and job prospects. (Networking, Myers could have said). It’s one of the forces in society that keep people separated into their places.

Matthew and Luke both have genealogies, placing Jesus in a long list of ancestors. Mark is uninterested in Jesus’ family line. Jesus’ biological family is outside the house; inside Jesus finds his real family. Obedience to God is its hallmark, not service to Beelzebul in Jerusalem or even in first-century Mediterranean “family values.”