The so-called “Little Apocalypse” in Mark is no prediction of a distant future end of the world. It is the rejection of an oppressive order centering around the temple and also a rejection of a violent attempt at restoration. Neither priests nor rebels could imagine a world without the temple, but Jesus can.

Twentieth in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and a Table of Contents are HERE.

Mark Chapter 13 is a chapter in the Bible people most like to write about. I’ll use that as my excuse for a post that is quite a bit longer than usual.

Jesus is about to leave the temple. (It’s still Tuesday.) On the way out Jesus pauses over a sight that wounds his heart and stirs him to revolutionary anger. Unfortunately, the incident has done mostly the first and not the second for us.

People are putting money into the temple treasury—large amounts in some cases. But a poor widow puts in two coins worth a few cents.

I always thought Jesus’ words that follow were commending the widow and affirming and encouraging the small sacrifices that poor people make. They should feel good that their contributions rank ahead of even the large contributions of the wealthy. That thought exists in our romantic imaginations. It may even be a good thought. But it is nowhere at all in Jesus’ actual words:

Amen, I say to you, this poor widow put in more than all the other contributors to the treasury. For they have all contributed from their surplus wealth, but she, from her poverty, has contributed all she had, her whole livelihood. (Mark 12:43-44)

The temple has taken from this widow “all she had, her whole livelihood.” It’s an illustration of all that has been wrong with the temple cult. And Jesus is angry.

Predicting the temple’s destruction

Anger boils over when, on leaving the temple, one of the disciples gushes: “Look, teacher, what stones and what buildings!” (Mark 13:1) After all they had seen that day—the withered fig tree, the symbolic destruction that Jesus has enacted in the temple, especially the plight of the now penniless widow—the disciples still don’t understand.

Do you see these great buildings? [Jesus screams] There will not be one stone left upon another that will not be thrown down. (Mark 13:2)

The Romans destroyed the temple in the year 70, having conquered a rebellious faction of Jews and sacked Jerusalem. You could say Jesus’ prophecy came true, but not exactly. The temple was burnt, not thrown down; and there were some stones still on others, specifically the Western Wall, also called the Wailing Wall. It still exists.

The date of Mark’s Gospel and the question of Jesus’ divinity

Myers thinks the inaccuracy of the prediction is evidence that Mark wrote before this traumatic event. Scholarly opinion is divided. Many will say only that Mark wrote “around” the year 70. A few claim a much earlier date.

Some conservatives assume that the post-70 date is a liberal idea: Mark makes up the prophecy based on what has already happened. We get rid of Jesus’ ability to foresee the future; we get rid of his divinity. I don’t think that’s a fair reading of a scholar’s motivation. At any rate, even if the words are Jesus’ own, that doesn’t prove divine ability to foresee the future.

In fact, it’s a poor argument for divinity since Jesus doesn’t describe the future accurately. My thought is that Jesus did say that the temple would be destroyed. I think he was speaking metaphorically about a corrupt and cult system about to meet its doom—no divine powers required for that. Perhaps Jesus was doing what people do often, predicting, guessing about, the future. It could have been wishful thinking that Jesus utters in well-justified anger of the moment. None of these alternatives is evidence either for or against Jesus’ divinity.

Mark’s community and the time he wrote

The question of the date of the Gospel, and also its location, is important for Myers but, I think, not crucial. His political reading works better if Mark’s community is in the throes of the Jewish rebellion. That means a date prior to 70 and a location in or near Palestine. (Traditionally many thought Rome was the Gospel’s site.) I like Myers’ proposal, but I’m not committed to it.

Myers imagines a scene in Palestine or nearby Syria near then end of the Jewish War, the year 68 or 69. The rebels are desperately pressuring and threatening Mark’s community. Against them are the powerful Romans. A third faction consists of some Jews who have all along cooperated with the Romans. This scene works well for what Myers sees as Mark’s attempt to keep his community separate from all three factions. After the year 70 the rebel side drops out as a viable threat, but Mark’s insistence on neutrality still works well enough. Mark still would want to counter some Jewish Christians thinking along the lines of, “Maybe we should have joined the rebellion.”

Apocalypse and Mark Chapter 13

The political context within which Mark wrote, with Jerusalem about to fall or having recently fallen, helps to interpret the section we call the “Little Apocalypse.” In the story it comes right after Jesus’ daring—and it will turn out dangerous—comment about the temple’s destruction.

Mark sets the stage. (13:3-4) Jesus is sitting for a long, important lesson. He is “on the Mount of Olives opposite the temple,” physically embodying the opposition he has just enacted symbolically. The disciples Peter, James, John, and Andrew get him started:

Tell us, when will this happen, and what sign will there be when all these things are about to come to an end.

“All these things … come to an end” seems an odd way to refer to the temple’s destruction that Jesus predicted. The disciples seem to be reading apocalyptic significance into Jesus’ words, and they are not wrong. Jesus has refused a request for a sign before. We’ll see how Jesus handles the request this time.

First (Mark 13:6-13) we get some predictions of events that Mark must have seen by the time he wrote, whenever that was:

- Many coming “in my name,” saying, “I AM HE!” deceiving many. Jesus doesn’t toot his own horn like that, but other wannabe saviors did, especially when it seemed for a while that the rebellion might succeed.

- “Wars and reports of wars.” All talk was of war and getting rid of the Romans in the years before the final defeat.

- “It will not yet be the end.” This line, I think, is one count against a pre-70 date for the Gospel. After 70 Mark would have known it wasn’t “the end.”

- Earthquakes, famines, “the beginnings of the labor pains.” This is apocalyptic language and it will get much stronger presently.

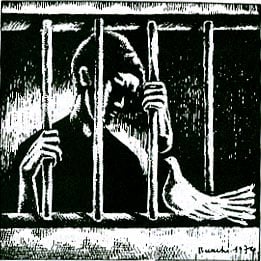

- Persecutions connecting with mission—in another sandwich construction. Mark and his community probably already discovered that mission and persecution go together. Here are the three parts of the sandwich:

- Persecution: “They will hand you over to courts and beat you in synagogues. You will be arraigned before governors and kings.”

- Mission: But the gospel must first be preached to all nations…. Say whatever the Spirit gives you at that hour.”

- Persecution: “Brother will hand over brother to death…. You will be hated by all.” There must have been dissension even within the Christian community.

“(Let the reader understand)”

With this parenthetical remark to his first readers Mark assumes they can understand these puzzling words of Jesus:

When you see the desolating abomination standing where he should not (let the reader understand) … (13:14) [Then Jesus gives advice to his endangered followers.]

The apocalyptic phrase “desolating abomination” appears in Daniel (11:31, 12:11) and 1 Maccabees (11:54). It first referred to an incident after the Greeks conquered Jerusalem in 168 B.C.E. Antiochese Epiphanes IV had desecrated the temple by dedicating it to the god Zeus. We later readers also know that Jerusalem fell again in the year 70. The Roman army had surrounded Jerusalem some months before that. Myers thinks that by “desolating abomination” Mark refers to this military threat. (p. 335)

Jesus’ words of advice which follow support Myers’ interpretation. You will see that they make good sense as warning in the situation of a community expecting military defeat. They also make good enough sense at a post-70 time as reassurance. Christians who fled the oncoming Roman attack hear in Jesus’ words that they made the right decision. These words make much less sense as a prediction of woes attending a literal end of the world, as the traditional understanding of this passage goes. Here is Jesus’ advice:

Head for the mountains. Forget about getting your cloak or anything else out of your house. Pity any women who are pregnant. Hope it’s not winter. (Mark 13:14-18, my free rendering)

“In the tradition of Jeremiah … defying the logic of patriotism,” Myers says, “Mark abandons Jerusalem and the restorationist project as a lost cause.” (p. 335) Jesus rejects both the rebel radicalism of reconstructing a new order on the old model and also any moderate reform movement. “Both perspectives fail to see anything fundamentally wrong with the ‘system.’” (Myers, p. 339)

Apocalypse sounding more apocalyptic

So far Mark’s Jesus has answered the disciples’ question about signs with only what people by Mark’s time either experienced or could guess on their own. Well, Jesus does throw in a brief taste of apocalyptic language (“earthquakes” and “famines”). Now the language turns heavily apocalyptic with lots signs that might seem to be about the end of the world.

The language is appropriate, Myers says, “for this is precisely how any Jew would have interpreted Jesus’ rejection of the symbolic center [of Jewish life, the temple].” Jesus is at war with the “powers.” They physically manifest in Jewish and Roman systems of oppression, but in the first-century Mediterranean mind they exist just as truly in the heavens. Jesus looks forward to the end of these heavenly but physically embodied powers:

…the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from the sky, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken.

And then they will see ‘the Son of Man coming in the clouds’ with great power and glory, and then he will send out the angels and gather his elect from the four winds, from the end of the earth to the end of the sky. (Mark 13:24-27)

To the disciples’ question, “When?” Jesus seems to give a perfectly clear answer:

Amen, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place. (Mark 13:30)

This reads very much like the earlier “Amen, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the kingdom of God has come in power.” (Mark 9:1) We could attribute to Jesus a mistake, which by Mark’s time would have started to be quite obvious. But why would Mark have repeated the saying that everybody could see was a mistake? Or else the reference is to something more down to earth, something that has happened or is in the process of happening. In a previous post I suggested the powerful-Kingdom-of-God language refers to Mark’s community as it began to gather folks together to live the revolutionary life of God’s Kingdom. Here I think “these things,” which sound so world-ending, refer to that same small, revolutionary start-up community. A new kind of life, almost a new world, is beginning.

The fig tree (again) and the absent master

Two parables (Mark 13:28-37) conclude this discourse, one before and one after the mysterious saying about “this generation.” Here Jesus makes the answer to the “When” question anything but clear. But he does have some clear advice: “Be patient. Watch.” Having disallowed fighting, even when pressured to join the “cause,” Jesus now says, “Don’t rush things. Don’t imagine that you can make it happen.”

Jesus tells them to learn from a fig tree again. When the leaves sprout, you know summer is near. Such a simple thing! Why does Jesus bother to say it? Perhaps because there’s nothing more complicated to say. Neither you nor the fig tree can make a revolution or the summer happen. Be patient. But you can do something while waiting. The master has gone and left servants in the house, each in charge of various duties. But no one knows when the master is returning. Even I don’t know, Jesus says. So stay on your toes. Live the life of God’s Kingdom. And watch!

We’ve arrived at the entrance point to the story of Jesus’ passion. Myers says, “Mark is debating the rebel recruiters, engaging them in a fierce war of myths over popular kingship ideology.” (332) There is no doubt that Mark sympathizes with the rebels, the Jewish establishment, but Mark is preparing the reader …

… for a discourse not of revolutionary triumphalism, but of suffering and tribulation. Against rebel eschatology, Mark pits the death/life paradox of his own narrative symbolics and the politics of nonviolence. (Myers, p. 333)