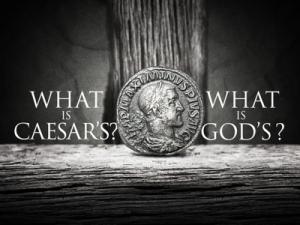

Separation of church and state is not a first-century idea. Rendering something to Caesar and another something to God, getting along well enough with both Rome and the temple establishment, is not Jesus’ way.

Nineteenth in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and a Table of Contents are HERE.

Jesus knows how the world works. There’s the overarching power of Rome and the subordinate Jewish religious apparatus. The latter holds on to as much of its own power as the greater power allows, getting along well enough. In this context Jesus utters the famous statement:

Repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God.” (Mark 12:17)

Up to this point, traditionally, the whole Gospel of Mark has gotten a non-political, spiritual interpretation. Here the interpretation can’t get around the politics. Jesus addresses Roman power directly. Having missed the political implications of all that has gone before, interpreters have applied their own modern political categories. The favorite of these is separatio;n of church and state, a formula for accomodation. Myers abandons this tradition. (Myers 312-314)

Reviewing the politics in Mark’s Gospel

Throughout his book Myers helps us see incidents with their political import. For example, there’s the devil named “legion,” a Roman military division. Jesus dismissed this devil into a battalion of pigs and they were cast into the sea like Pharaoh’s horsemen. Even the title of Mark’s book and Jesus’ favorite word, “Gospel,” is political. The “good news,” was originally empirical propaganda; now Jesus commandeers it for his own purposes. (See this post and this.) With such a history it’s hard to believe Jesus would suddenly turn accommodationist and just get along.

Jesus hasn’t been getting along with either of the great powers, the religious elite or the Roman conquerors. Tuesday in that first Holy Week arrives and Jesus engages in two more confrontations. He stands against the one power and then the other. First he shows up the authority of the Jewish leaders for the spurious thing that it is. Then he tackles the Caesar question.

By what authority?

Representatives of the highest Jerusalem authority, the Sanhedrin, try to take Jesus down in front of the crowds. They only end up humiliating themselves. (Mark 11:27-33)

Chief priests, scribes, and elders demand to know by what authority Jesus does “these things.” (This is the day after the demonstration in the Temple.) Jesus counters with a question about John the Baptist’s authority. Is it from God or from people? Jesus knows that they won’t dare say it’s from people for fear of angering the crowds, who regard John as a prophet. On the other hand, they can’t say from God because they obviously aren’t following John.

Sheepishly they claim, “We do not know.” Fair or not, Jesus gets away with not answering the Sanhedrin’s question either. But everybody knows now what the temple rulers’ authority is worth. They can’t even speak their minds for fear of the crowd.

The tenant farmers (Mark 12:1-12)

Now Jesus goes on the offensive with a parable that deals with the fundamental economic reality that peasants faced. Mark 12:1-9) A peasant worked land that may once have belonged to his family but was lost due to debt. Every 50th year, the “Jubilee Year,” land was supposed to return to its original owners. Then the process of accumulation by the wealthy and powerful and dispossession of the poor would have to start over. But the people who count had long since been ignoring that rule had long since been ignoring that rule. By Jesus’ day—as in ours—nobody had to start over. Most of the land was in the hands of the temple aristocracy, absentee landlords collecting exorbitant rent from peasant tenant farmers.

Jesus’ Parable of the Wicked Tenants turns the tables. The members of the aristocracy are now the tenant farmers and God is the absentee landlord. Jesus describes the vineyard deliberately to bring to mind its symbolic reference to Israel, which the aristocracy should be tending. The landlord sends servants to obtain some of the produce, but the tenants mistreat and kill them. Finally the landlord’s son comes, and the tenants plot to kill him, thinking that then the vineyard will be theirs. This is not as crazy a scheme as it sounds. Seeing the son, the tenants reasonably conclude that the landlord is dead. The property being ownerless, anyone may claim it, first come first served. (Myers, p. 308)

The chief priests, scribes, and elders rightly conclude that the parable is directed against them. Instead of tending God’s field properly or even badly “they have contrived to ‘own’ it, (i.e., turn the worship of God into a profitable commercial interest).” (Myers, page 309)

Jesus and David’s kingdom

Jesus concludes the parable with the Old Testament passage most often quoted in the New:

The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; by the Lord has this been done, and it is wonderful in our eyes. (Mark 12:10-11, from Psalm 118:22-23)

“Most rabbinic literature interpreted David as the ‘rejected one’ of the Psalm,” Myers says. (p. 309) It sees the elevation of the “stone” as the restoration of the Kingdom of David. On Sunday with palms the crowd thought Jesus would be the great restorer. But Jesus is not interested in a Davidic Kingdom lifting its head again in triumph. He will soon (Mark 12:37) disown any link to David by quoting David’s own words.

David himself calls him [the messiah] ‘lord’; so how is he his son? (How could the Messiah be David’s son and David’s lord? The implication is, He can’t be both.)

Again I find myself understanding a saying of Jesus in a completely new way just by having the political context brought to the fore. Jesus here is refusing the title Son of David. Jesus has no intention of restoring a kingdom from the past.

What about the payment to Caesar?

Jesus has rejected Jewish leaders and even the concept of a Kingdom of David. How does he stand with the other power in the Mediterranean world? That is the dangerous challenge some Pharisees and Herodians raise:

Is it lawful to pay the census tax to Caesar or not? Should we pay or should we not pay? (Mark 12:14)

This is about the same as asking, Do you support us, who collaborate with Rome, or side with the rebels? There’s capitulation on one hand and peril on the other. Jesus does not capitulate. He insists that we

… pay back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s. (Mark 12:17)

It looks like a nice parallel. Christians have found in this saying a way of living comfortably with whatever worldly kingdom happens to be in force. But the parallel breaks down because of the infinite distance between Caesar and God. Myers says,

In other words, no Jew could have allowed for a valid analogy between the debt Israel owed to Yahweh and any other human claim. There are simply no grounds for assuming (as so many bourgois exegetes do) that Jesus was exhorting his opponents to pay the tax. (Myers, p. 312)

I would add: “As if Caesar had ever given the Jews anything that was due to be paid back.” What at first seems to be an answer to the question (a convenient answer at that) turns out, on second thought, to be no answer at all. Jesus has simply reversed the challenge. Now it’s a choice between God and Caesar. Where do Jesus’ opponents place their allegiance? My translation says they were “amazed.” Looking at the Greek word (exethaumazon), I’d say it was more like “wonder-struck” or even “thunderstruck.”

Jesus lets his opponents make their own choice, but his choice is clear. Pay back to Caesar his due, i.e., nothing. Pay to God everything.

The most dangerous way

Myers’ method is to read the entire Gospel of Mark politically. He looks for political meaning throughout—and finds it! Thus he also finds the appropriate context for interpreting the saying about rendering to Caesar. Without that the saying is ambiguous enough for a commentator to insert his or her own political leanings.

Myers says most commentators do exactly that. They ignore the context and the political challenge facing Mark’s community. Should they align with the rebels fighting to restore a Davidic empire or with those who collaborate with Rome? Jesus’ choice, Mark says, is the most dangerous of all: Don’t line up with either of these powers.

The next post is on what’s called Mark’s “little apocalypse.” This is where Jesus gets eloquent about his third way.