Introduction to a Series on the Earliest Gospel

A worldly spirituality moves more deeply than usual into the heart of matter, That theme has occupied my thoughts for some time. Now I’m pursuing it through a reading of the Gospel of Mark. There I’m finding that material concerns, including what we call politics, economics, and culture (but a first-century Jew would have known them simply as life in the world), are Jesus’ concerns. First of a series on the Gospel of Mark, with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus.

This Introduction will continue after this look ahead.

The Worldly Spirituality of the Gospel of Mark, Table of Contents (Chapter and verse of Mark’s Gospel in parentheses)

- Introduction. The Worldly Spirituality of the Gospel of Mark

- Mark’s Gospel, the Dangerous, Political Beginning: ‘News of Victory.’ Mark commandeers the Roman propaganda term “Gospel” for his own purposes. (1:1)

- John the Baptist and the Stronger One. John the Baptist preached forgiveness, but for which sins? (1:2-13)

- “Fishers of Men,” Fish Hooks for Whom? Jesus’ saying, “I will make you fishers of men,” is more aggressive than you might think. It echoes the prophets Jeremiah and Amos. They prophesied that oppressors of the people will be dragged away with fishhooks (1:14-20)

- An Exorcism: Jesus Upsets Business as Usual. Jesus’ preaching “with authority” is an attack on the scribes, but it’s the devil who complains. (1:21-28)

- The Challenging Symbolism of Miracles of Healing. More than compassion for individuals motivates Jesus to heal the sick. He challenges the purity and debt codes oppressing the poor. We’d call it social justice. (1:29-45)

- Meals, Fasting, and Sabbath: Taking on the Pharisees. Jesus challenges the three basic elements in the Pharisees’ cherished, perhaps well-intended but in effect oppressive, symbolic order. (2:1-3:6))

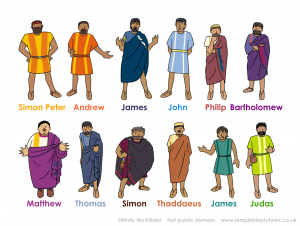

- The Twelve Apostles, Start of a Community of Resistance. An essential part of Jesus’ work is the community which he founds. Mark makes it clear to his readers that this is a political reality, a government in exile. (3:13-19)

- Who or What, Exactly, is Possessed? Establishment figures call Jesus a worker for Beelzebul, but Jesus turns that charge against them. (3:20-35)

- Parables, Earthly Stories with Heavenly Meanings? … Not! Jesus tells stories with comfortably familiar scenes and strange twists. The tendency of modern interpreters has been to find heavenly meaning in the earthy tones, but in the Gospel of Mark at least the meaning as well as the tone is quite earthly. (4:1-34)

- Feeding the Multitudes (Twice) and Gentiles in the Kingdom of God. The details of the two stories of feeding the multitude show that Mark has a serious purpose in the duplication, and it isn’t necessarily to get history right. Both Jews and Gentiles belong in God’s Kingdom. (6:34-44, 8:1-9)

- The Shape of the Kingdom. God’s Kingdom is a kingdom of equals, with Jews and foreigners, rich and poor, women and men on equal footing. Jesus exhibits this reality with his own self when he loses an argument to a woman foreigner. (5:1-43, 7:24-30)

- Gathering Darkness and Two Sparks of Hope. Jesus’ path is getting more dangerous, and at the same time he seems to be increasingly isolated from his own disciples. Here we’ll see how Mark encourages his readers with hopeful clues about the people close to Jesus. (8:22-26, 9:14-29)

- Transfigured but not Triumphant. Is Mark, in the Transfiguration scene, giving us a brief glimpse of Jesus’ triumph after the cross? Myers believes it’s the cross itself that comes into view here. I add my own idea. (8:1-9:13)

- The Resurrection. Puzzling with the Disciples about Jesus’ Predictions. The Gospel of Mark has Jesus predict both his passion and his resurrection three times. The disciples don’t understand the passion because they don’t want to. They don’t understand the resurrection because they can’t. (9:9-10, 30-32

- Mark’s Catechism, House Rules for God’s Kingdom. Being a Christian in the first century meant that powers of the world outside would consider you a threat and possibly kill you. They were not threatened by your strange religious beliefs but by your revolutionary way of acting. (9:33-10:31)

- Palm Sunday: A Procession with an Anti-climax. We think of the crowd of Passover festival goers in Jerusalem in Jesus’ last week as fickle—wild about Jesus the Messiah on Sunday, calling for his execution on Friday. Actually they never changed their minds. They simply discovered, possibly as early as Sunday evening, that their hopes and Jesus’ purpose were not the same. (11:1-11)

- Monday and Tuesday Morning: A Fig Tree and the Temple. One of the surest facts about Jesus’ life is the demonstration in the Temple. We call it the “cleansing of the temple,” but the symbolics surrounding a fig tree clearly indicate that Jesus means destruction, not reform. (11:12-25)

- Not Rendering to Caesar. Separation of church and state is not a first-century idea. Rendering something to Caesar and another something to God, getting along well enough with either Rome or the temple establishment, is not Jesus’ idea. (11:27-12:17)

- A Plague (or is it Stars Falling) on Both Your Houses. The so-called “Little Apocalypse” in Chapter 13 of the Gospel of Mark is no prediction of a distant future end of the world. It is the rejection of an oppressive order centered around the temple and also a rejection of a violent attempt at restoration. Neither priests nor rebels could imagine a world without the temple. It would be the equivalent of a world-ending catastrophe. (12:41-13:36)

- The Sacrament of Touch: We Touch Jesus’ Body and the Discipleship Story Carries On. Touch is what makes the connection the Church has with Jesus real. It’s like the matter of a sacrament, given form by Jesus’ teaching. Teaching alone couldn’t keep the discipleship community together. The memory of Jesus’ touch gathered them once again after they had fallen apart.

- Civil Disobedience and the Puzzle that was Thursday: Why did Jesus Turn Himself In? Jesus enters Jerusalem knowing authorities there wanted to kill him. For about four days he skillfully avoids capture. Then, having left his disciples a memorial of himself in the form of a meal, he gives himself up. Both the first and the last parts of that puzzling behavior call for explanation. The practice of civil disobedience in our day may provide a helpful analogy.

- Atonement and Some Odd Hypothetical Questions about Disciples. Jesus reconciles us to God. Jesus saves. But how does that work? This post claims disciples are an essential part of atonement. Without disciples Jesus’ work and his suffering are for nothing.

Introduction continued

You see from the Table of Contents that I’ll be going through the Gospel of Mark rather slowly. Most of the posts cover small sections of what I’m sure you will find is an amazing book, especially if you have your Bible open as you read these essays.

A close look at this Gospel, such as I’m finding as I read Ched Myers for the second time, reinforces my conviction that spirituality can be very worldly indeed. This is a spirituality that follows the path of the Son of God into the midst of materiality, even—in fact, especially—into the political/economic/cultural world that humans have made through (among other more positive things) greed, hunger for power, and willing complicity with or unwilling toleration of these.

In Mark the Evangelist’s world, politics, economics, culture, and religion were not separate. Mark could not write theology without political implications or address a political situation without being either attacked or applauded or both religiously. The same goes for the economics of that day (the great wealth disparities) and the culture (whom you could touch or with whom you could eat, for example). Myers deals with these interconnections and in doing so throws surprising light on obscure Bible passages including some that I didn’t know were obscure.

Teaser: Maybe you doubt that prayer can lift a mountain and send it crashing into the sea. Maybe you wonder why the gospels give you two miracles of feeding the multitudes. Maybe you’re shocked when Jesus calls a woman a “dog.” And maybe you’re perfectly comfortable when Jesus calls his followers and you “fishers of people.” If so and if you like surprises, stay tuned.

A note on miracles

Myers treats both the ordinary and the extraordinary deeds of Jesus and others as events in the Gospel of Mark. He describes their meaning without affirming or questioning their historicity. For the most part I will do the same. There is a problem with this procedure, however. Whether or not a storied miracle actually occurred concerns the meaning of the story for Mark’s first readers and for us but in different ways. For example, if a first-century Jew believed someone had performed an extraordinary deed, one unexplainable in reference to the normal course of events, there would have been two possibilities: it was either a work of God or a work of the devil. For me, and I dare to imagine for you also, that’s not a viable alternative. A miracle is a work of God or it didn’t happen, or didn’t happen the way it’s told.

Modern Bible scholars, including Catholics, do question the historicity of many miracle stories. One such scholar is Cardinal Walter Kasper. In Jesus the Christ he sees a trend in the written traditions that became the New Testament. Miracle stories get more numerous and more amazing as you go from earlier to later writings. The same human dynamic of exaggeration, he assumes, was operating in the earlier oral traditions of remembering and telling stories. This reduces considerably, he thinks, the historical kernel behind the stories—but doesn’t eliminate it.

Kasper offers what he says is the opinion of most scholars: Jesus had the reputation of miracle worker during his lifetime. This reputation must have had some basis in historical fact. About what that basis was he is not so definite. Jesus may not have walked on water, calmed stormy winds, or multiplied loaves. The so-called nature miracles are the most doubtful in this view. But a historian, even without faith, can reasonably conclude that Jesus probably was both healer and exorcist.

You will find numerous healings and exorcisms in the posts that follow. They are part of Mark’s story. I leave the historical questions to others.

Catholic and politically active

Finally, I need to say a word about the value of a political reading of any gospel. We Catholics have a huge presence in American political life. At the time of this writing, a majority of the Supreme Court are Catholic. Catholic representation in Congress is considerably larger than our portion of the whole population. The American bishops are well-known for their positions on abortion, contraception, and same-sex marriage. Recently they have started speaking more forcefully on other issues like immigration, poverty, racism, and even health care, war, and environment—catching up, I would say, to where they were in the post-Vatican II decades of the last century.

The other notable thing about Catholic political presence is that we are all over the map on the issues. We are wasting our rich tradition of engagement with the world’s problems because we speak with a divided voice. We have thundered on some issues and whispered on others just as central to our biblical faith. Can we even relate the Bible to a specific bill in Congress on a specific issue? We could do that better if we realized the Bible is more about this life than about life after death. It would help also if we thought as much about oppressed groups, oppressing systems, and movements for change as about individuals in need.

I found Ched Myers political reading of the Gospel of Mark inspirational and insightful. Based on the number of times I was able to say, “Aha! That’s what it means” about passages that didn’t make much sense before, I think he’s also right.