In my daily prayers I ask God for favors: Help this one recover from surgery. Help that one find a job. Help me write this post. Am I asking for miracles? This post looks at miracles as metaphors of a transcendent God’s involvement in creation. I interpret those metaphors a number of ways. That’s how it goes with God. With only univalent, literal language God cannot be named accurately but becomes an idol, a piece of the world.

Tenth in the series “Stories of Jesus and the Character of God.” In this series I probe what historical Jesus scholars can say about the humanness and the earthly career of Jesus. Beyond that historical research cannot go. The ultimate objective is to let this Jesus reveal the character of God. Contents and links to other entries in the series here.

Faith, seeing the world as God’s creation, is a fundamental attitude that enables one to perceive something as a miracle. It doesn’t work the other way around. It’s a mistake to try to use miracles to prove that something beyond this world, namely God, exists. I suppose that’s not a universally held opinion, but it’s a common one among theologians.

First century Jews saw the world not as nature but as creation. The miracles fit into this view as extraordinary and unexpected, provoking amazement and awe. They make a person think not that there is some disconnect between cause and effect, where a god intervened into the “normal” workings of nature, but that there must be some unexpected meaning to all that exists if this sort of thing can be part of it.

God’s relation to creation

The real question about miracles, then, is: How does God relate to the world? The Bible testifies to a “God who in constantly original ways offers his love to human beings in and through the events of the world.” To those events God gives “full secular autonomy.” (I’m following again Walter Kasper in Jesus the Christ. The quote is from p. 94)

Must we see the meaning of any event either in God’s purpose or in its own place and role in world affairs? Kasper says it can be both:

[T]he basic law of the biblical relationship between God and the world [is] that the unity of God and the world and the autonomy of creation are not inversely but directly proportional.” (p. 94)

And,

The intensity of creation’s independence grows in direct and not inverse ratio to the intensity of God’s action. (p. 95)

I think I could feel really comfortable about miracles, even as a lover of science, if I could make sense out of those two quotes. Some common metaphors by which we think of God’s relation to the world, though, work in an opposite direction. We think of God as the one who makes and the world as the thing that is made. God is actor, world is acted upon. The more God works, the more the world is worked upon and the less independent it is.

An abundance of metaphors for God and world

From Pagan thinker Gus DiZerega I caught an interesting take on the metaphor of making. He says we make things to use them. This way of imagining God’s creation, he says, takes away from the created world its intrinsic value. He prefers images like emanation and giving birth. DiZerega’s two metaphors are also in the Bible.

An important fact about metaphors is that they are not literal. No metaphor speaks entirely accurately about God. God’s reality is beyond the reach of any metaphor and all of them together.

That being the case, it’s good that there are many ways to think of God’s relation to the world. Perhaps one or more would help us think Kasper’s thought. God’s activity and creation’s autonomy are in direct, not inverse, relation.

Christians love to think of God as Father and, quite a bit less often, as mother. Parents lead their children toward independence. They gradually withdraw support, though not love, as children “get on their own two feet.” This relation is still inverse, not direct. Does God get less involved as we become more independent.? And when the children grow up and the parents of the metaphor die, what then? Does God eventually become irrelevant as “death of God” theologians said in the 1960’s? Is God just an idea that humankind may have needed at one point, but it’s time to put such a childish thing away?

New metaphors

If Kasper is right that there’s a direct relation between God’s involvement and creation’s autonomy, the images of making and parenting don’t show it. If God’s involvement and creation’s having its own proper role grow together, we’ll need some new metaphors. Fortunately, we’re not nearly out of things to compare God to.

I’m thinking now of a sculpture made of wood. Not just any wood but a gnarled twisted piece of driftwood. The beauty of this sculpture comes not from the sculptor’s mind alone but also from what the sculptor can see in the wood. The artist cooperates with the wood. A large part of the work of the artist is looking at the wood, and the more the artist does that, the more the wood contributes to the final product. Much, or maybe all, of great art has something of that aspect, where the activity of the artist, which may be very intense, is not controlling but more like letting something be.

Consider another art, storytelling. A lot of the involvement of the writer is letting the story tell itself, letting the characters be who they are, letting a situation unfold. An author may say something like “When I discovered that my character had spent all that time in jail….” Or, “When I finally found the end of the story….” (These are thoughts of Mesha Maren, author of Sugar Run, interviewed on National Public Radio) The Book of Genesis names God’s creativity with the words “Let there be….”

There is love in the artist’s or storyteller’s letting be If God’s relation to the world is like this, then it also is a relation of love. I never felt more myself than when it dawned on me that I was deeply in love with the woman who became my wife, and she with me. Our involvement with each other and our being truly ourselves, our best selves, were in direct relationship—just what Kasper was talking about.

God’s activity and the world’s true identity

Artist, storyteller, and lover are three metaphors for God’s relation to the world that let us see how God’s involvement and the world’s having its own nature and identity, can rise together in a direct ratio. Then we can say, along the lines that Kasper gives, that a miracle is not a place where the world’s coherence breaks down, overpowered by God’s activity, but a place where the world’s true identity shines. The next post in the “Stories of Jesus” series takes aim at that identity.

When I ask God for favors in prayer, I don’t imagine I am asking for a miracle in the sense of something that the world can’t give but God can. I’m asking that God continue the creative involvement with the world that has been God’s modus operandi from the beginning. I often (usually?) don’t get what I ask God for. In those cases I hold to what a religious sister told me long ago: God sees “something better.”

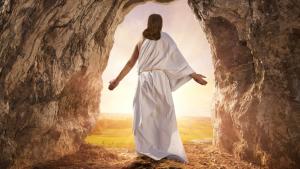

Image credit: 1stDibs, via Google Images