Thinking about Debt with Michael Hudson

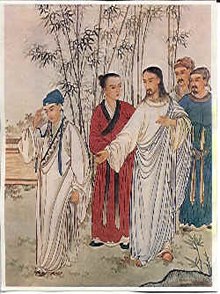

Jesus, a non-believer in trickle-up economics, chases the money lenders out of the Temple in illustration on cover of “… and forgive them their debts” by Michael Hudson. (Image credit: michaelhudson.com)

Almost all of the new money the American economy has produced in four decades has gone to the wealthiest people. We’ve been living with this trickle-up economics ever since Ronald Regan introduced the phrase “trickle down” in his 1980 presidential campaign.

Long before then the common belief, including among Catholic bishops and economists, was that “a rising tide lifts all boats.” Less metaphorically, in the immediate post-World War II years, it was thought an expanding economy would benefit everybody. So Catholic ethics turned from opposing materialism to growing the economy, or added the latter to the former. See this quote from one of my posts on Catholic Modern by James Chappel:

The one dogma that remained the same [between liberals and progressives] however was the belief that time alone would solve the problems of poverty and inequality—time for the economy to grow.

After 40 years of neoliberal economics, featuring tax cuts and small government, many economists have become critical of the result. These include two Catholics, Anthony Bennett and Michael Hudson. Their ideas will be featured in a series of posts that began with this post on Anthony Bennett. Hudson’s …And Forgive Them Their Debts is another major source for this series.

Credit and debt in ancient history and the Bible

Michael Hudson has made a study of the effects of debt in both modern and ancient societies. His oft-stated conclusion is, “Debt that can’t be paid won’t be paid.” He correctly predicted the Latin American debt defaults of the 1980’s and the financial crash of 2008. (Interview of Michael Hudson in “The Honest Sector.”) For one like Hudson it raised two questions: Is it natural in an economy for debt to pile up to the crisis point? For “trickle-up to be a second name for any economic theory? And is there a more humane solution than the common prescription of fiscal austerity. In Latin America and around the world that IMF solution often meant a country couldn’t assure its citizens of the necessities of life. That’s the definition of crisis debt. Hudson decided he had to “write a history of how countries have coped with paying debts in the past.”

… and forgive them their debts is the result of that decision. In it Hudson details the origin of money in the ancient credit-based economies of the Near East. He also shows the unequal positions of creditors and debtors, what ancient rulers like Babylon’s Hammurabi did about it, and how the Bible and even Jesus got involved. The first sermon of Jesus that Luke records and many of his stories are about money, debt, and forgiving or not forgiving debts.

Debt forgiveness in the ancient world

The Bible’s Book of Leviticus (25:10-11) offers peasant farmers a deal that seems too good to be true. Every 50th year, the “Jubilee Year,” debts that had accumulated since the last Jubilee were to be canceled. Peasants who had sold themselves to debt slavery would regain their freedom. Land lost through debt foreclosure would go back to the original possessors. It seemed to most scholars too utopian ever to have been put into effect. A typical modern economist would say an economy can’t survive such a practice.

The Bible got its idea about debt forgiveness from Babylon. There debt forgiveness was a regular and successful practice. Babylon is where most 6th century Judeans spent 50 years in exile. And Babylon got this answer to debt from earlier Near East societies. From Sumer to Hammurabi and on to the Byzantine Empire, debt cancelations kept economies from collapsing under unsustainable debts. Trickle-up happened, but it was regularly countered by return to the “Mother,” the previous state.

Early records on clay tablets show how credit and record keeping was key to ancient economies. Peasant farmers obtained seed on credit. At compound interest, the loans would double in five years. (Scribes could handle that math.) It wasn’t a problem usually because farmers could pay their loans in grain at harvest time. Grain could be converted to silver for wider-ranging trade. Hudson sees the origin of money in debt and credit exchanges.

Peasant had more than seed loans to pay back. They needed meat. They needed beer from the ale houses. All of that they obtained on credit and paid back from the harvest. They also owed the king, from whom they received the land. They paid their tax bill with military service or work on public projects like temples, palaces, pyramids, and infrastructure.

Ancient trickle-up economics

All this meant that the king had an interest in keeping peasantry as a viable occupation for his subjects. Against the king’s interest a class of financiers developed. Naturally their interest was in keeping their loans intact. Unfortunately that led regularly to separation of peasants from their land and even their freedom. Debtors’ prison didn’t exist yet, but slave labor on someone else’s land did.

The worst fears of peasant life came about because of the inevitable uncertainties of farm life. Rain and sun didn’t always come in the right amounts. Some years a farmer could not pay back his springtime loan. He could extend the loan, at compound interest, in hope of a bumper crop the next year. But eventually large numbers of peasants faced some difficult options. They could pay off their loans with part of their land, again putting future farming success in doubt. They could sell family members as slaves to work for their creditors. As a last resort, they could sell all their land and enter the slave market themselves.

One way or another large numbers of peasant farmers ended up working on land they did not own, owing rent in addition to seed and life-support costs. Creditors, a whole class of financiers, got richer and eventually powerful.

Creditors versus kings

From the king’s point of view this was a disaster. A financier class was hoarding up his supply of needed labor and military service. As long as that class was small and weak or even part of the king’s own family or retinue, the solution was simple. The king could simply declare all debts for farm work and other life support canceled. Kings regularly did exactly that, often the first year or two after ascending the throne. Another likely occasion was the onset of a war, when kings would need a healthy, loyal supply of soldiers from the peasantry.

Inscriptions on clay tablets are records mostly of financial dealings, and among them are many announcements of debt forgiveness, freeing peasants, and returning them to their lands. Economics historians, with their bias in favor of creditors, mostly ignore this ancient practice. The Rosetta Stone is famous, but not for the message it contains—forgiveness of debts.

Unfortunately, kings could not hold out against the rising power of financiers. Rulers took to adding “fine print” to their announcements of debt freedom to deal with evasion techniques. Eventually creditors became more powerful than royalty. Greece and Rome–democratic strivings in the former and republicanism in the latter–had their own concept of freedom; and it did not include freedom from debt for peasants. A populist would-be ruler like Julius Caesar was an endangered species. It’s Greek and Roman belief in the “sanctity”– Hudson’s word – of debt that has endured to our age. That same belief, Hudson says, led to the downfall of Rome through impoverishment of the common people.

A look ahead

From the early Near Eastern empires to our day, money has naturally moved upward. The progressive era from the Great Depression to about the 1970’s temporarily arrested this trickle-up tendency. But the stabilizing method of debt forgiveness practiced by early kings has been largely lost. The loss is especially acute in international economics when poor countries’ unsustainable debt piles up.

Future posts in this series will explore applications of the historical practice of debt forgiveness. I’ll look at

- how the Bible’s Jubilee Year, if it ever was more than words on scrolls, fared in the time of Jesus and the Pharisees,

- how the great Rabbi Hillel, teacher of Saul before he became Paul, innocently or not, served the interests of creditors over debtors,

- what Jesus’ attitude was, and how the Church spiritualized the idea of “forgive us our debts” in a time of decreasing hope for the peasant class,

- also how my two authors, Anthony Bennett and Michael Hudson, imagine a modern economy that includes debt forgiveness as a stabilizing element.