In a section of Mark’s Gospel that my Bible calls “The Tradition of the Elders,” Jesus argues Sacred Scripture with some Scribes and Pharisees. To argue Scripture is to take a stand in a larger polemic about the nature of God. Often it also envisages divine support for one side or another on a hot-button political issue. Both of these factors animate to Jesus’ harsh criticism of the tradition of the elders.

This is the sixth post on William R. Herzog II’s Jesus, Justice and the Reign of God. Earlier posts in the series are:

- The Historical Jesus and the Transcendent God in the Work of William Herzog

- Context Group Continues the Long History of Witnessing to Jesus

- Jesus Heals a Paralytic and Opens a Temple-Free Zone of Grace

- The Temple, Jesus, and the Little Traditions of Village Life

- A Rich Man Follows All the Old Rules. Or Does He?

The “Tradition of the Elders” controversy, Mark 7:1-23

This long section of Mark’s Gospel has two scenes and six parts.

Scene one:

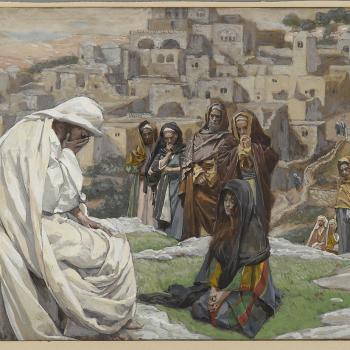

- Some Pharisees and scribes have come to Galilee from Jerusalem. They object to the disciples’ low regard for the tradition of the elders by eating with “defiled [unwashed] hands.” “Why do your disciples not live according to the tradition of the elders,” they ask Jesus.

- Jesus quotes Isaiah against these hypocritical Jerusalem officials. They “honor [God] with their lips.” They teach “human precepts as doctrine” and abandon God’s commandment.

- Jesus specifies: They have abandoned the commandment to honor father and mother by the rule of Corban. That is, they claim they needn’t support their parents if they simply dedicate any such support to God. “And you do many things like this,” Jesus accuses them.

- Jesus pronounces about defilement: Not what goes in from outside but what comes out from inside is what defiles.

Scene two:

- Jesus explains his saying about defilement privately to his disciples. “Thus he declared all foods clean.”

- Wrap up. A list of vices that come from the human heart: fornication, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, deceit, envy, slander, pride, etc. all come from within. They defile.

Did the Church and Mark make up the controversy?

Did the conflict between Jesus and the officials happen much as the Bible story reports? Or did Mark or an earlier writer put together disparate elements from the Church’s memory of Jesus and add their own pieces? Herzog is more inclined than some to locate a Bible story in the life of the historical Jesus. This incident, where Jesus argues about the tradition of the elders, is a case in point.

Mark and the post-resurrection Church contributed much in the construction of the above story, Herzog admits. (p. 170) Mark explains to his readers what “defiled hands” are – unwashed. There’s a long Markan parenthetical description of Pharisees’ traditions around food. Mark explains the meaning of “Corban” – dedicated to God. “Thus he declared all foods clean” is clearly Mark’s comment. The concluding list of vices that defile is most probably from the early Church.

Then there is the apparent composite nature of the text. Sandwiched within a controversy about food is a long section criticizing another hypocritical practice of the Pharisees – the tradition of the elders. One result is that the question the Jerusalem officials ask in part 1 above is not answered until part 4

Finally, the quote from Isaiah that the text attributes to Jesus follows the Greek translation, which the Church used. But Jesus would have known Isaiah in Hebrew, which the Greek translates rather freely. Herzog juxtaposes the two versions:

First, Hebrew: “… and their worship of me is a human commandment learned by rote.”

Second, Greek and Mark: “… in vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the precepts of men.”

Some scholars have concluded that at least this part of the story is the work of the Greek-speaking Church. (p. 170) By this analysis the story disintegrates into many unrelated parts.

Placing the story in the career of Jesus

Herzog proposes that the parts are not as unrelated as it may seem. He identifies the literary form of the story as “challenge-riposte.” (p. 171) The Jerusalem officials indirectly challenge Jesus by questioning the behavior of his disciples. Jesus answers (the riposte) with an attack that appears to change the subject. Instead of defending his disciples’ dinner behavior, Jesus goes on about Corban, with a quote from Isaiah to strengthen his position. This counterattack, Herzog says, is exactly what Jesus must do in an honor-shame society. (p. 174) He can’t start out by defending the disciples as we might expect. That explains the long gap between the officials’ question and Jesus’ answer.

The two elements composing the story, the diet rule challenge and the tradition of the elders criticism, fit together well enough as challenge and riposte. It makes sense as one of many conflicts between Jesus and the elite class.

Herzog also looks at the Hebrew text of Isaiah and finds that it fits well in Jesus’ parry of the originating question. The pharisaical purity regimen is just a matter of following rules one can recite “by rote.” Jesus’ argument does not depend on the Church’s Greek text but works just as well with the Hebrew text that Jesus knew.

The story, Herzog says, may not have happened exactly as written. There are the Markan explanations and the list of vices that probably comes from the Church. But the controversy with the scribes and Pharisees over dietary rules and the tradition of the elders in general may be fairly true to life.

The center and the periphery, temple expectations and village life

One might wonder what business Pharisees and scribes from Jerusalem had in a small village in far-off Galilee. They were there, Herzog says, to “monitor compliance with the version of … the Torah as interpreted by ‘the tradition of the elders’” – the temple’s version of God’s Law. (p. 171)

The villagers would have resented such interference. Surprisingly, their own view of the Torah, God’s Law, was stricter in some ways than that of the Judeans. They certainly didn’t approve of Corban, which was not so much a rule as a way of getting around a rule. Pharisaic innovations, like Corban and dietary rules, “nearly always worked against [villagers’] interests.” Conflict between the center and the periphery was inevitable, and Jesus took the villagers’ part.

By rejecting ritual ablutions for hands … Jesus and the disciples “in effect reject the Pharisaic conception of the social order and the values that order mediates.” (p. 172. Herzog quotes context scholar Bruce Malina.)

The defiled hands controversy is part of a larger issue: “whose vision will govern the people of the land.” Naturally, control includes a monetary element. As relates to diet, the tradition of the elders requires pure cooking pots and serving dishes and tithing of food purchased. (p. 173) Concern for the poor, which Jesus elsewhere calls the “weightier matters of the Law” (Matthew 23:23), suited the villagers’ moral perspective.

What kind of God?

Herzog so regularly finds in Jesus’ words and actions an advocacy for the oppressed poor that one wonders if there is room for God in Jesus’ concerns. That is a common criticism of Herzog’s earlier book Parables as Subversive Speech. Jesus, Justice, and the Reign of God addresses explicitly what may have passed unnoticed in the earlier book. The deepest issue in Jesus’ confrontation with Jerusalem officials over the tradition of the elders, Herzog says, is the nature of God.

The conflict is over core values. (p. 177-78) For the Pharisees it’s purity; for Jesus, forgiveness. The one stresses God’s holiness; the other, God’s mercy and compassion. For the Pharisees God defines, separates, orders, brings order out of chaos. For Jesus God liberates and provides. God draws boundaries in a defensive strategy — or God reaches out in mission and hospitality. God of the center, temple, city, and richly favored ones maintains stability — or God of the periphery, prophets, and village poor risks challenging the status quo.

The issue on which Pharisees are most eager to preserve the separate identity of God’s people is the Sabbath. The next post will see Jesus honoring the Sabbath. Unlike the Pharisees, Jesus honors God’s people first.