BOATILA-MANJI

Vera Johnston

June 27-July 4, 1890.

“Native Boats Off Bombay.”[1]

We hired local boatsmen to take us to the steamer in their native-vessel which they called manjis.[2] It began to rain as soon as we sailed out of the port, but the sun shined so bright that it hurt one’s eyes. The little manji dived and climbed the crests of the wave. The helmsman began to sing his endless song, which was picked up by the rowers. Not a single job in India is complete without such peculiar “hey, let’s whoop” songs. It went something like this:

Pull, brothers!

Well, let’s pull it

The steamer is leaving!

Well, let’s pull it! Siam steamer!

Pull, brothers!

It is raining! Big rain!

Pull, brothers!

The master of baksheesh will give a lot!

I was so afraid that we would have to stay in Bombay again, that time seemed to drag on endlessly for me. I didn’t even want to look at anything, although on the right side of the manji the foggy bulk of Elephanta Island emerged. It was soon obscured by the green, mountainous Butcher’s Island, so-called because that was where all the slaughterhouses of the white butchers were located. The natives opposed the destruction of cows, an animal sacred in the eyes of the Hindu. Finally we found ourselves in sight of the Siam, which was just about to raise her ladder. I began waving my umbrella and shouting, although I should have realized that they couldn’t hear me. Charley started laughing. The boatsmen threw a rope onto the steamer, and pulled the dancing manji up to the ship with great difficulty. I dropped two umbrellas and a shawl into the water, but it was only a half-grief for me. I knew that the Siam wouldn’t leave without us.

The Siam turned out to be a very nasty, dirty, old, and small ship. We were very disappointed, because, being familiar with the elegant giants of the P & O Company, we did not expect this. It had been sold by the German Line, Norddeutscher Lloyd, to the Oriental Line in 1875. They were afraid to let it out of the port for more than a week because they fully expected it to sink on each voyage. The second class deck was very unattractive, and half of it was occupied by a dirty cow’s stall. As there was nothing to do, we went to our room. The cabin was so small, hot, and stuffy that it was difficult to breathe in it. We tried to change rooms, but all the compartments were occupied. Charley lamented, saying that if it weren’t for my gorodnitsya, we would now be traveling in first class, on a large ship, and would already be in Aden. I tried to prove that it was better to suffer for several days in order to bring all sorts of wonders for myself and my friends. But if I knew what these few days would be like, I probably would have sacrificed all my property.

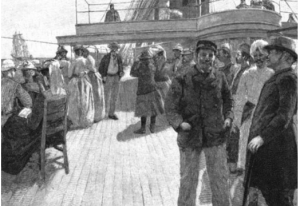

Promenade Deck Of A P & O Liner.[3]

Coming out onto the deck, we saw a crowd of passengers. Several launches were still swaying around the ship, and friends and loved ones shouted and laughed. The tearful passengers on the Siam waved goodbye, while those remaining wished strength to those leaving. A half-naked old man, a newspaper peddler, was lowering himself overboard by rope into the boat. Suddenly the Siam trembled, the water hissed, the last echo answered the farewell roar of the whistle, and we set off.

Everyone was at the sides of the steamer. Rocky islands, crowned with coconut palms, appeared, and disappeared behind us. We saw the beautiful Sailors Home, an inn for sailors of all nations, behind it the Apollo embankment, where the people of Bombay take elegant evening rides. A monument to the Prince of Wales flashed between the houses, then a railway-train rushed by, from the windows of which heads in multi-colored turbans stuck out, like colorful toy balloons.

The bulk of Victoria Terminus, the University of Bombay, the sheds in the shipyards where ships are built—everything floated away from us. No sounds reached us from the shore anymore. Soon the Tower of Silence on Malabar Hill disappeared from sight, and we moved away from the shore. Farewell merciless sun and hot earth! Farewell muddy waters, mosquitoes, snakes, fevers, and rashes! Farewell rich nature, with your mighty trees and colorful birds! Farwell you harmless, deceitful, and pitiful natives! Farwell to your temples, your ugly idols, your stupid luxury, and your filthy poverty! Farewell you land of emeralds and pearls! Farwell India!

Sailors Home. (Source: Old Indian Photos)

The steamer rocked violently, and we barely made it to the deck at dawn the next day. Wandering the Indian Ocean when there is a monsoon raging there requires great courage. But when tormented by fevers and liver pain, it seems that everything in the world is better than the slow torture to which India subjects the Europeans. Moreover, it is most convenient for an Anglo-Indian official to ask for sick leave to get out of India. The entire deck—on which it was impossible to find a dry place—was lined with an assortment of wicker-chairs and canvas furniture. (On English ships passengers must provide their own furniture.)

A whole volley of officers were returning home to Britain, having served several compulsory years in the Punjab. Sepoys, that is, soldiers who were recruited from the natives, are not dragged along by the officers. Rather, they remain in India, where they are allowed to re-enlist in a new regiment. They are drilled and trained much better than those soldiers who can be seen riding around in London. The sepoys are recruited from the Rajputs, and from the Gurkha tribe living in the mountains near Nepal, not from the peaceful tribes of the valleys. The Gurkhas gave their name to the most valiant regiment in India, which contributed to many British victories.

The British are playing a dangerous game with these sepoys. Many prudent people, who are usually laughed at, fear the future outcome of training sepoys. White officers, in contrast, are surprisingly frail in appearance, and short in stature. I knew a lot of British officers, and I always found myself taller than any of them, causing them to ask me, with undisguised annoyance, “Are all Russian ladies as tall, as you?” As an outsider looking in, one cannot help but understand that it is not the prestige of European education that is keeping India from a new uprising. For mercy’s sake, wake up India! Shake off the petty differences of beliefs, and caste, and end the hostilities of one another! The Anglo-Indians themselves will regret that they trained the sepoys so well. Then Calcutta, which is so conveniently located both for escape and for the safe dispatch of orders, will not help. This capital of the Indian Empire is located in such a place that exit from it along the Hooghly branch of the Ganges is completely guaranteed. The population around it is peaceful and incapable of rebellion. Moreover, the youth of Bengal are brought up by English leaders in such a way that they cease to be Hindus without becoming Europeans. I don’t dare to decide whether the British teachers are giving orders intentionally or not, but a native youth, having been to the university, becomes a talkative, useless rag.

Vasiliy Vereshchagin. “Suppression of the Indian Revolt by the English.” (1884.)

We must hope that we will never see the beating of European women and girls such as the shame brought upon Lucknow in 1857. People who see the indignant natives of India tied to cannons in Vereshchagin’s famous painting as a reproach to the hard-heartedness of the Anglo-Indian government are completely unfair. Every father, husband and brother, every European nation in these circumstances would have done exactly the same thing, and would have been right. But one cannot help but be surprised at England’s shortsightedness.

Among the officers traveling with us in Siam was the regimental priest. There was also some engineer who did not suffer from seasickness at all, and a lady, the wife of one of the officers, who was completely ill, which, however, did not stop her from laughing languidly with her companions.[4] My sympathy was especially aroused by a tea planter from Assam, who was traveling with three small children.[5] We recognized her as an old friend, as we had traveled together on the Arcadia on our journey to India, but she had only two children back then.[6]

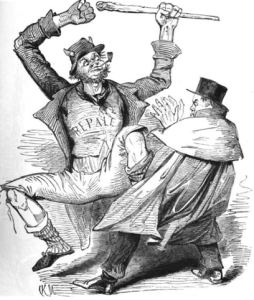

Irish Caricature in Punch.[7]

I noticed her in the very first days of the voyage, back in the Bay of Biscay, because her face was strikingly similar to the caricatures of the Irish depicted in Punch. That is to say, with a short nose, long upper-lip and ear-to-ear mouth. The bad impression was smoothed over this time. Her situation was too difficult, and yet she was able to tell us a few kind words about the pitiful change in me and “my dear gentleman’s” appearance.

We were all tied to one another, and stationary objects on the deck, with scarves and ropes. Despite this precaution, our seats slid and unraveled with every movement of the steamer. Their creaking could not even be heard over the noise of bad weather, and the splashing of water. Several young postal officials, kela-sahibs carrying Indian mail to Port Said, jostled between our chairs, merrily talking, and chasing each other. They didn’t care about bad weather; they are familiar people. The sailors cheered us with their appearance. English naval officers are great dandies. I have never seen so much as a fluff on their cleverly tailored frock coats. They always have their hair cut in the latest fashion, and their linen is snow-white in all weathers. Only now their legs were bare to the ruts; for even they could only walk barefoot on the wet deck of the rocking steamer. No one puts on shoes during the Monsoon; it is impossible to take off boots that are swollen from salt water. I took the opportunity to admire the intricate tattooing that every self-respecting English sailor is said to be completely painted with.

Small waves continuously jumped onto the deck from both sides. Puddles of greenish water spilled onto the deck, and ran to the sides, only to rush back to the sea again with renewed vigor. My chair was pushed right up to the cow stall. I dutifully endured the close proximity, although the smell of manure and fresh milk affected me even worse than the smell of the warm rotting steam mixed with machine oil and rubber, that is characteristic of all steamships. Bags of crackers and buckets of beer were constantly brought to the cow, but this, obviously, did not console her. She mooed very pitifully.

What a night it was! I could never imagine anything like this. There was not even the thought of sleep. You had to hold on tightly to the copper railings of the bunks. Water rushed in like waterfalls, despite the fact that both openings from the deck were carefully blocked. Already everywhere in the dining room and in the cabins, there was about half a foot of water. The deck-chairs, with their legs screwed to the ship, turned creakingly with each new shaft. The dishes in the buffet breaking, and the bulbs of electric lamps flickered with a ringing sound. Eventually something happened to the electric battery, and we were plunged into darkness. The servants, in a hurry, did not know whose call to answer, where to run, or what thing to support on the fly. We had two kerosene lanterns that gave us scanty light, but they fell off the tables. One went out in midair, the other shattered, spreading a bright flame for a moment, but was extinguished and wiped out by the weight of other things rolling around on the floor. New lanterns were brought in, but they suffered the same fate. It seemed that light and liberation would never come.

The tired brain sinks into tetanus. If the thought of danger comes, it dissipates by itself, you forget to ask others about it, you don’t have time to formulate it in your own mind. Drowsiness or delirium came over me. Something disgusting, alien, and huge suffocated me from time to time. Sometimes I came to my senses and began to think about some trifles that had not the slightest connection with the current situation.

When morning came, I realized that Charley was completely ill, far worse than me. I could achieve nothing with my inquiries. I struggled to reach the bell, and asked to send for a doctor, but I didn’t wait for him to arrive. Having barely reached my top bunk, I also lost consciousness, probably from the movement. When I came to my senses, I was already on the first landing of the stairs to the deck. I was supported by the usual maid, a kind-hearted postal official, and a young doctor with such a haggard face that he could envy any passenger. He told me later that he still wasn’t used to the monsoons. When the doctor left, I began, as usual, to look around. My God! What a picture! The collapse of all decency and modesty! Everyone was barefoot, barely covered with flannel night suits, grabbing other people’s pillows and blankets, and not thinking about disassembling the furniture according to their belongings.

As soon as I calmed down, a whole wall of sea water washed over us again. My couch was pushed right up to the side of the ship, and overturned. While I myself was falling, I managed to see the husband of the only lady of the regiment. He was rushing in my direction with a face distorted in horror before he also fell. It turned out that the chair on which his wife was lying on was raised so high by the water, that when the Siam moved again, it would inevitably be washed overboard into the raging ocean. The Muslim sailors managed to pull the lady down, but her chair floated away. The same virtuous postal official who had brought me on deck, picked me up and took me to the only smoking room on deck. I laid down on the floor, and could not have left without outside help, even if they kicked me out with sticks. Another wave rushed towards us with even greater force. Streams of water ran into the smoking room. A terrible crash deafened us. The stands on which the large rescue boat was fastened had broken away, and the boat floated away. Some men leaning out of the windows of the room said that the boat had floated onto the deck again, but they did not have time to capture it.

For another whole week, we were subjected, day and night, to the same torment of heat, water, stench, and physical pain. For a long time it seemed to us that we would never see land, that there was nothing in the world except this raging aquatic emptiness. The wind tore off our shawls and hats. Two more boats were carried away by the waves, and all the furniture on the deck was either washed away or broken. For a long time we howled and whistled in all the vents and pipes. For a long time everything around us, animate and inanimate, ached and groaned. For a long time walls of water spread over our heads, climbing into the cabins and into the hold. After nine days we reached Aden, a trip that should have only taken five.

To top off all the horrors, the day before liberation, news spread throughout the Siam that the captain, whom no one had seen in second class, had lost his way. Charley asked one of the sailors if this were true. The sailor, with a good-natured smile on his dark face, said that it was true. The storm had carried us far from our intended path, but that there was no danger. A passing doctor confirmed the sailor’s words, adding as a form of consolation, that this gave us the right to boast when describing our worries, and that we had almost been to the equator! But the travelers had a strong confidence that no one knew where we were, and fear visited even the most intrepid. Despite our fears, by evening the excitement died down. The dead swell, which I could not stand before, continued, but no one paid attention to it. What does a person not get used to? The previous days, to my surprise, I could eat and even take a nap. But then we all finally calmed down. Everyone got dressed and cleaned up, everyone got to know each other and talked happily.

The postal official, my savior, I learned, was named Francis de Souza. He asked me when the Russians will finally come and avenge them, the humiliated and insulted? People like him are quite the Indian type. They are terribly proud and touchy, and at the same time they themselves invite harshness from the unceremonious English. They are embittered against everything British, and express their embitterment with uncontrollable talkativeness, and are offended that the young Anglo-Indians are not eager to become familiar with them. I introduced Francis de Souza to Charley as an equal. This simple courtesy on our part made him constantly run for water and ice for us, getting us fruits that were rare on the ship through his friend, the maid. He also continued to bore me with complaints about the British, political intrigue, and the hope that Russia would arrive in India as liberators. For some reason, he spoke to me in no other way than in French, although he knew English better, and his phrase, full of mysterious gloating: “Quand la Russie viendra!” buzzed my ears.[8] I ended up avoiding him, despite his kindness and my pity for him. He noticed this, was offended, and probably began to think worse about the Russians.

That evening the officers, perked up, decided to give us an amateur concert. I climbed into bed early and thought about getting a good sleep. But sleep did not come! A long round bag was hanging from the mast into a closet with spare ropes, onto which the window of our cabin overlooked. Such bags were used to pump air into the lower floors of the ship.[9]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company. Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s Guide Book For Passengers. Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company. Printed For Chicago Exhibition [Chicago Agency] Chicago, Illinois. (1893): 79.

[2] According to Hobson-Jobson, a Manchua, or “Manjii” was “a large cargo-boat, with a single mast and a square sail, much used on the Malabar coast.” [Burnell, Arthur Coke; Yule, Henry. Hobson-Jobson: Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases. John Murray. London, England. (1886): 420.] The term seems to have also applied to the boatsmen themselves.

[3] Hunt, Ridgely. “Steamship Lines Of The World.” Scribner’s Magazine. Vol. X, No. 3 (September 1891): 267-287.

[4] The newspapers name the following British officers on the Siam: Capt. F. Bennet, Capt. Bruce Blair, Surgeon-Major G. Deane Bourke, Capt. B. Creagh, Capt. Harvey, Capt. A. King, Capt. L.G. Oliver, Lieut. J.M. Stewart, Lieut. Vincent. The regimental clergyman whom Vera references, was presumably the Rev. A. Bridge. The wife of the officer may have been “Mrs. Vincent,” who was married to Lieutenant Vincent.

[5] Improving one’s station in life by becoming a tea-planter in Assam was an enticing prospect to many lower-class laborers in Britain. It was said that in Assam, “the climate was heavenly, and the scenery glorious, the work fascinating, and the pay and prospects alluring.” [Cox, Edmund C. My Thirty Years In India. Mills & Boon. Limited. London, England. (1909): 2.]

[6] The only person who seemingly fits this description is one Mrs. Leach, who arrived in India on the Arcadia with an infant, and left on the Siam with a child and an infant. There is a discrepancy by one in the number of children listed in Vera’s article, but this might be creative license on Vera’s part. [“Port Of Calcutta.” Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England.) November 20, 1888; “Shipping Intelligence.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India) July 2, 1890.]

[7] Punch. Cartoons From “Punch.” Vol. I. Bradbury, Agnew & Co. London, England. (1906): 43.

[8] “When Russia arrives!”

[9] Johnston, Vera. “Home From India.” Russian Review. (May 1891): 245-278.

%2Bc1900.JPG)