GOING HOME

Vera Johnston

June 27 1890.

We were detained in Bombay for a whole week. Our things, due to the mistake of the station master in Calcutta, turned out to not only not arrive, but to be sent to the northwestern provinces. We had to let the large steamer of the Italian company Florio Rubbattino pass, although the tickets had already been purchased, and Charley and I were bored with the familiar Bombay. We already knew everything that travelers usually examined in it. In addition, there were the tropical rains in India. In Allahabad, which we had just left, it was still dusty and stuffy, and the water for our bath had to be cooled with ice beforehand, so as not to bathe in boiling water. But on the Coromandel Coast, in Calcutta, and everywhere in the south, the rain poured in buckets from morning to evening, and from evening to morning. This was the third rainy season I had experienced in India, and I have to say, even the worst heatwaves are better. You can’t go out, and everything in the houses are rotting. The P&O steamer, S.S. Siam, was heading to Aden again on June 27, and we were terribly afraid of missing that one, too.[1]

“P&O Offices In Bombay.” (Source: Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s Guidebook For Passengers.)

Early in the morning of the day of our scheduled departure, Charley went to Victoria Terminus to visit the ticketing agent, and although I was already very tired of the daily trips to this station, I was even more tired of solitary confinement in the hotel, so I went with him. The Victoria Terminus Railway Station in Bombay was considered the most extensive and elegant in the world. The Anglo-Indian government spared no expense so that it might immediately awe the inexperienced traveler with its magnificence when they first set foot on Indian soil. At home in the British Isles, the British do not have such stations, and there is no need to talk about the dirty, damp, red betel spattered, strikingly slovenly stations in Madras, Calcutta, Allahabad, and other cities of the Indian Empire. Let’s say that in Victoria the Gothic and Moorish styles are mixed too unceremoniously.[2] But the Briton does not pursue this, and the native, be he a Mahratta, a Parsi, a visiting Bengali, or a Tamil, will not notice this at all. Moreover, the infinite number and variety of decorations, moldings, cornices, gilded vaults, marble columns, mosaic floors, angels on pointed turrets, are intended to entertain the eye and edify the mind. On the middle and largest dome are the Queen and Empress herself, and under the canopy where the trains enter, each cast-iron beam is already a chef-d’oeuvre.[3] One soon notices that the style of the building is lame, that its bulk overwhelms everything around it to the point of ugliness, and, that, despite all its decorations, it seemed like a rough patch of new sackcloth on an old thin canvas. Eugène, a great admirer of Indian antiquity, once compared this station to the Anglo-Indian government itself, “sitting heavily over a decrepit, crumbling, and dying India.”[4]

Victoria Terminus.

Charley soon disappeared into the endless passages of the Station, accompanied by a Mahrat in a very beautiful scarlet turban with a gold border, and three small earrings in his ear. I stayed on the landing stage. What an endless variety of types, costumes, head decorations and dialects. The saying that there is nothing written on a person’s forehead does not apply in India. Here on people’s foreheads, if not written, then a lot is depicted. Brahmins can always be recognized by their large face, smeared from the bridge of the nose to the roots of the hair with white paint, with a central red stripe. People engaged in the study of secret sciences smear their foreheads with clay from the bottom of some sacred ponds. Shiva worshipers make two transverse gray stripes on their foreheads with a black circle above them, or just three stripes, depending on caste.

Persons belonging to the famous Salvation Army also wear badges on their foreheads: one red stripe to symbolize the shelter of the Savior, another yellow to symbolize the fire of the Holy Spirit, and a third blue to signify the purity of their own hearts. There are always many of them among the native crowd. They are dressed in the same way as the natives, that is, an arch, a piece of muslin around the hips and legs to the knees, a flannel jacket or bare-back, bare-feet and a turban or bare-head. The turban and dhoti for the Salvation Army were salmon-colored, and the jacket was red. The hair was shaved, or left to grow to shoulder length.[5]

North Indian Salvation Army Corp.[6]

The women of the Salvation Army, mostly captains, also wore native dress. It’s difficult to imagine anything funnier than one of these captains, an old and fat Englishwoman, with glasses and very thin hair, who once turned to us with the question—“Are you saved?” that is, do we understand the teachings of Christ according to theirs? Some changes and additions were made to the clothes of the venerable propagandist, but still the muslin vestment was too light and transparent for her form. The Salvation Army in India makes very few converts, and then, only among the pariah. Their nightly processions, with the singing of psalms composed on motifs from operettas, with pipes and drums, are very annoying to the peaceful inhabitants of Bombay, Madras, and other southern cities.[7]

When Charley was freed, having finally received our luggage, we decided to go around the native quarters again. The ship was not leaving soon, and there was still a lot of time left. On leaving the station we encountered Sir Dinshaw Petit, the only brown-skinned baronet in the United Kingdom. He was a very kind old man, with a long gray mustache and quick, clear eyes. The story about how Dinshaw Petit became a baronet is a departure from my story, but it is well worth mentioning. A few months ago, an incident occurred in the English Parliament. The Lancashire representative in the House of Commons brought a whole deputation from the Manchester cotton manufacturers to the Marquis of Salisbury. The deputation said that the competition of Indian manufacturers had become so intense that they, the Manchester bosses, would soon have to go down the drain, and that if he, the Marquess of Salisbury, did not put a rein on their enemies, then the whole of Lancashire, with Manchester at its head, would refuse to support the Prime Minister. The next day the question was raised in the House of Commons that the Indian manufacturers were being terribly inhumane to the thousands of poor blacks working for them. It was decided to reduce the number of working hours in Indian factories. By this measure, of course, the price of Indian production rose, Lancashire’s competition with them became more secure, and the humanity of the British government showed itself on the best side.[8] Dinshaw Petit should have been the first to suffer, since he was the largest cotton manufacturer. Having read this this whole story in the newspapers, we felt sorry for the old man whom we liked. But then we heard that he was made a baronet because of a huge monetary donation he made in favor of lepers.[9] Whatever the direct purpose of this good deed, his factory was now beyond the squeezing and nagging of the Anglo-Indian guardians of order and silence.

After parting with the Parsi, we went to the fruit row. The cleanliness of the markets in both Calcutta and Bombay is amazing. I remembered a market, the Armenian Bazaar, in Tiflis, my hometown. In essence, all three were very similar. The same multilingual, noisy crowd; the same darkish rows of shops with dry, pickled, and fresh fruits; the same cheerful, inviting, and good-natured, merchants open-measuring and hanging practically the same produce of amazing shapes and tastes that in Europe they cannot name or imagine; the same thoughtful figures, flashing in the crowd, and stern, chiseled, profiles of tall Afghans, delivering dried apricots and Aloo Bukhara from the Black Sea to the Bay of Bengal. It is the same in all three of these bazaars; the same lines of camels, with the occasional ringing of a bell hanging from the one that goes in front. In a word, everything is very similar, but not clean and orderly. To understand the difference, suffice it to say, that the markets in Calcutta and Bombay smell only of melons, pineapples, oranges, and flowers. In Calcutta, flowers are sold in garlands, and chains, and intricately woven tassels—all made from flowers. It’s rare to find a bouquet for a boutonniere folded in the English style. In Bombay, in addition to chains and bracelets, they sell funny bouquets. The bouquet is densely arranged in the form of funnels of flower heads pressed against each other; a stick is stuck into the end of the bouquet, and at the other end there is the same funnel of the same flowers, usually tuberoses, only smaller; everything is decorated with tinsel gold and silver threads and sprinkled with rose water, even though it spoils and drowns out the smell of the flowers. Lovely things are sold in every little shop in India, on all the railways, and are so cheap that there was nowhere for an apple to fall in my suitcases and chests. I had to explained to Charley what a gorodnitsya is, and with each new purchase I proved that there was a place for a porcelain figurine.[10]

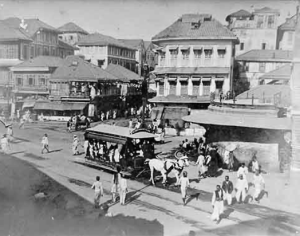

Horse-Drawn Tram, Bombay.

We drove, once again, through the dirty, noisy streets of Bombay, hemmed in on both sides by tall buildings with many balconies, in which mostly lived representatives of the richest Jain sect in India; we passed their temples, which differed from the temples of the Mahrattas—native Bombays and Hindus zealous in their beliefs—in greater beauty and less diversity. The horse-drawn trams, like long wooden buildings, go everywhere, and is a common honor among the natives. It is a most unpleasant anomaly in a setting with palm trees, minarets, pointed pagodas, and round vaults reminiscent of Harun al-Rashid. The annoying, sharp bells of these horse-drawn trams, and the thunder of the sleds on the smooth winding ground, reminds one of our Russian Ice Mountains. It’s almost amusing when it enters a crowd of Muslims washing their hands and feet in a marble pool in a stream of water in front of the entrance to a mosque.

Hotels in India are designed in a European manner. There are paths along the corridors for the servants, who knock on the door before entering. Silence and decorum are maintained at the common table, where native-plants are placed in porcelain vases. Only the punkah fluttering above our heads, and the barefoot servants drawing operating it, remind us that we are in Asia. The guests, of course, are multi-colored, with a predominance of British officers. The servants in Bombay, although dark-skinned, consider themselves Europeans. They were mostly descendants of the Portuguese from Goa, in Southern India, and are devout Catholics. Our five-story hotel, The Watson’s Esplanade, also had the peculiar distinction of being made entirely of iron, and could be disassembled and assembled in a short amount of time.[11]

We had barely finished dinner when we heard a knock on the door to our room. It was our old friend, the Parsi, Rustomji, who was unaware that we were leaving that day, and came to invite us to his home before our departure. I had never been to a Parsi home before, the house of Dinshaw Petit, the only Parsi we had previously visited, was much more like the old Peterhof Palace than the abode from Scheherazade. We threw our things into boxes to be sorted out on the ship, thus buying us an hour to visit Rustomji’s home.

Watson’s Esplanade Hotel. (Source: Old Indian Photos)

The Parsis are fire worshipers who were driven out of Persia by Islam, but they managed to keep their religious customs intact. They are the only people in India who do not even allow people of other faiths to look into their temples. I still managed to look, but I didn’t see anything except the fire on the altar and bare walls. Around the temple, Parsis sit on the rubble, and talk decorously about their affairs. The place in front of the temple is considered a legal club for all fellow believers, something like the Parsi Exchange. They have a lot to talk about. They are very skilled traders. Petty trade in Bombay is entirely in their hands. They also have capital with large turnover, which spitefully opposes the Jains. They are clean, honest, and they stand up for each other like a mountain. They are very strict, and patriarchal in family life. Parsi women can be recognized because they are the only ones in India who wear stockings and shoes embroidered with gara. They can also leave the house freely, and no Parsi will allow them to be offended on the street, even if he did not know them personally.

Many of the Parsis belong to the Theosophical Society, and we were destined in India to become especially acquainted with representatives of this society. We walked through some very dark and dirty streets. They were so narrow that even the Indian sun could not peer into them, and two people could easily say hello while standing on opposite sides. Steep, narrow, and dark stairs led us to Rustomji’s apartment, where we met his mother, a very beautiful, elderly woman, who sighed every now and then. We also met Rustomji’s legless sister, and his pretty, quick-eyed wife. But I didn’t see anything new there. The same, as in all Indian houses, spacious beds, with calico sheets, and mosquito curtains (the first two ladies live on these beds without getting off,) and the same old-fashioned trinkets, and fly-spotted pictures, displaced from Europe by newer tastes. We exchanged photographs, and Rustomji gave me an egg from the marble rocks of Jabalpur, known as a souvenir throughout India.[12] I gave Rustomji’s two nimble sons an English alphabet with pictures I had saved, and we said goodbye. When we arrived at the pier, it turned out that the last steam-launch from the ship, which was stationed about two miles from the shore, had left. We were late![13]

Bombay Harbor (Source: Old Indian Photos)

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] On June 26, 1890, Johnston officially went on leave. [“Bengal Civil Service Retired!” Homeward Mail From India, China And The East. (London, England) October 3, 1898.] The following day they were scheduled to depart Bombay on the P&O steamer, S.S. Siam, for Marseille. [“Shipping Intelligence.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India) July 2, 1890; “Departure of Passengers.” Homeward Mail From India, China And The East. (London, England) July 16, 1890.]

[2] The Victoria Terminus, completed in 1888, just a few months before the Johnstons first arrived, was conspicuous from every open space in Bombay. Like the Secretariat, the University, the Town Hall, and an array of other new buildings in Bombay, it was in the “Indo-Gothic” style which dominated the city. [Arnold, Edwin. India Revisited. Trübner & Co. London, England. (1886): 54-55; “The New Great Indian Peninsular Railway Victoria Terminal Building, Bombay.” Scientific American. Vol. XXVI, No. 677. (December 22, 1888): 10,815-10,816; Caine, William Sproston. Picturesque India: A Handbook for European Travellers. George Routledge And Sons Limited. London, England. (1891): 6.]

[3] Vera is mistaken, it was actually a statue of the Goddess of Progress.

[4] In her original text, Vera does not name Eugène, rather she writes: “A French friend of mine.”

[5] Commissioner Booth-Tucker, founder of the Salvation Army in India, stated: “When we came to India, we put our Salvation clock half an hour faster than the other religious clocks in India by adopting native dress. This was not fast enough to suit us, and so we soon put on another half-hour by adopting the fakir costume. This was still too slow, so we put on another half-hour by going barefooted. Too slow still, so we went in for Indian food. Not fast enough yet, so we started begging and living under trees, and then began to twist the hands of our clock to see if we couldn’t get another half-hour extra. English shirts were next discarded, and nothing but a light cloth kept for the shoulders. If we can find any fresh way of adding another half-hour, we are determined to do it. People may say, ‘How ridiculous and extravagant to have our clocks three hours faster than everybody else’s.’ Some would like us to keep Church of England time, and others Methodist or Baptist time, but we take our quadrants and have a good look at the Sun of Righteousness, so as to find out the correct time which is kept by the clocks of Heaven. No differences up there—all the clocks agree with the great ‘Thy-will-be-done’ clock-tower. Only the earthly clocks are a long way behind. We are getting ours regulated and are only sorry it has taken so long.” [Booth-Tucker, Frederick. Muktifauj: Or Forty Years with the Salvation Army in India and Ceylon. Marshall Brothers, Ltd. London, England. (1900): 74.] There seems to have been some pushback on this sartorial decision. In an 1889 article in Evangelical Christendom, it was stated: “It would be no self-denial on the part of the missionaries adopt the native costume; their dress is cool, graceful, becoming, and picturesque, and do not believe that there is a single missionary in the country who would not cheerfully adopt it if he thought that by doing so, he would in the least help on the work. But the Hindus have more than once declared when this matter has been put to them, ‘You are a foreigner; be a foreigner, and we will respect you, but try to imitate the Hindus, and hardly anyone will really respect you.’” [“Missionary Notes.” Evangelical Christendom. Vol. XLIII, No. 4 (April 1, 1889): 113-121.]

[6] Booth-Tucker, Frederick. The Consul: A Sketch Of Emma Booth-Tucker. The Salvation Army Publishing Department. London, England. (1904): 76.

[7] In an 1887 interview with The Pall Mall Budget, Commissioner Booth-Tucker stated: “The natives are very lively, and our services suit them admirably, whereas they cannot tolerate the dull, slow, long drawn out services of the regular churches. Then they like drums, they like the processions, they like the lively happy service, and, best of all, they like the singing.” [“The Saviours Are Coming.” The Pall Mall Budget. (London, England) August 11, 1887.]

[8] Gilbert, Marc Jason. “Lord Lansdowne And The Indian Factory Act of 1891: A Study in Indian Economic Nationalism and Proconsular Power.” The Journal Of Developing Areas. Vol. XVI, No. 3 (April 1982): 357-372.

[9] “The year 1890 brought further honours to Sir Dinshaw, but the satisfaction which they evoked was overshadowed by an irrevocable loss. On the 6th of March 1890, Lady Sakarbai, the partner of his fortunes and the coadjutor in his philanthropic schemes during more than half a century, died in Petit Hall, only ten days before an official announcement by Lord Reay, made on the occasion of laying the foundation of a leper asylum at Trombay by the late Prince Albert Victor, that in return for his munificent charities the Queen-Empress had conferred a Baronetcy upon Sir Dinshaw. The Press welcomed this signal recognition of his services, and the Parsi newspapers in particular congratulated the community on the presence in the city of two Parsi Baronets, who, by their personal endeavours had aided Bombay to justify her title of Urbs Prima in Indis.” [Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. Memoir of Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit, First Baronet (1823-1901.) Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1923): 48-49.]

[10] Vera uses the word gorodnichya in place of “porcelain figurine.” As the literal translation would be something like “little mayor,” I am assuming that this is some idiomatic expression of sorts. A Gorodnitsya Porcelain Factory existed in Russia at this time, and I suspect that gorodnitsya was a proprietary eponym that became generalized in the common vernacular to mean porcelain. Since gorodnitsya is made diminutive (gorodnichya) with the “chya” addition (e.g. Alexander–Sasha,) I’m assuming this to mean “porcelain figurine.”

[11] The lobby of Watson’s Hotel would have been full of barefoot “cotton-clad natives,” who wore turbans, fezzes, and other embroidered caps. Every guest that was checking in would have had their own native servant ready at hand. [Twain, Mark. Following The Equator. The American Publishing Company. Hartford, Connecticut. (1897): 348.] Many of these men had last names such as D’Souza, Gutierrez, and Rodrigues. They called themselves Portuguese, but to an outsider, they looked similar to other natives. Long ago their ancestors adopted the surname of the priest who converted them. Nearly three centuries after the first Portuguese Jesuit missionaries established a presence in Goa, the Indian Catholics navigated a world of liminal identity. [Rosales, Marta Vilar. “The Goan Elites From Mozambique: Migration Experiences and Identity Narratives During the Portuguese Colonial Period.” Identity Processes and Dynamics in Multi-Ethnic Europe. Bastos, José; Dahinden, Janine; Góis, Pedro; Westin, Charles. (eds.) Amsterdam University Press. Amsterdam, Netherlands. (2010): 221-232.] Goa, a little further south of Bombay, was once a splendid Portuguese capital, but it was now a “miasmatic wreck.” Her cathedrals and churches were roofless and in ruins. Only a few native nuns even remained to keep the sacred fire alight before the crumbling altars. The more enterprising Catholics found their “niche” in society working as traveling servants. (Being a Christian, they had no caste, and had no religious scruples preventing them from wiping razors after a shave or eating a meal after certain shadows fell on their plate.) In Bombay a veritable guild of “Goanese traveling servants” had formed, and when transient wayfarers landed on a P&O mail boat, one of the first things they were advised to do was to “send round to the Goa Club,” and request the Secretary to send him a traveling servant. [Forbes, Archibald. “My Man John.” The Lyttelton Times. (Christchurch, New Zealand) May 24, 1893.]

[12] “A lingam not formed with hands is esteemed most holy by the Hindu. Thus the marble eggs found in the river-stream of Jabalpur are eagerly sought for, and one of the most holy pilgrimages, especially for sanyassis and led by such, is to the natural lingam formed by the ice which issues into the cave at Amarnath.” [Tibbits, Cathlyn Pepper. Cities Seen In East & West. Hurst & Blackett, Ltd. London, England. (1912): 305.]

[13] Johnston, Vera. “Home From India.” Russian Review. (May 1891): 245-278.