THE TREE IN HELL

Charles Johnston

June 1890.

You enter Allahabad across the splendid bridge over the bright blue Jumna, whose sapphire streams stretches away as far as the eye can reach. A little to the south of the bridge the Jumna is joined by the sacred Ganges, and the two flow on southwards to the holy bathing places of Benares, the thrice holy bathing places in Benares the old Hindu gods still rule; but here at Allahabad we are under the patronage of Allah, “the most merciful and compassionate god” of the Muslims.

To the outward eye Allahabad is very like all the cities of upper India, bazaars of open shops, full of bright fabrics, jars, and cups of platters of gilded brass, or toys and nests of boxes painted brilliant green and yellow and red. The laughing chattering crowd in the bazaars is almost as many hued as these nests of boxes. Great tall Kabulis from Afghanistan, with yellow Jewish faces and flowing white robes, with turbans woven round a pointed cap, giving them something of the air of a medieval magician. Then there are pale Kashmiris, with Greek foreheads, and keen-eyed Punjabis, the descendants of the Muslim conquerors of India, with their tightly bound turbans of colored silk, and gaudy robes, and closely twisted trousers. Ass to these Persians and little Mahrattas, and Biharis, and Bengalis, with their bare heads and dark shining locks, and you have some idea of the motley spectacle that opens out before us in the streets of Allahabad. I have always noticed that Indian towns where there is a fair mixture of Muhammadans and Kabulis, have a far more Oriental look than towns whose population is nearly all Hindu. Bombay, for instance, is far more like a page torn out of the “Arabian Nights” than is Calcutta, for in Bombay the Muslims and Parsis and Sindhis, with their bright-colored robes and gaudy turbans, fill up a brilliant picture that has far more romance and far more affinity to Aladdin’s garden, than the monotonous white scarves and bare heads of the dusky Bengalis. Bombay belongs far more truly to the real Orient than does Calcutta, although Calcutta is many hundred miles further to the east.

The most notable things in the bazaars here in Allahabad are the Delhi embroideries, the Benares brasses, and the pottery from Mooltan. Of the Delhi embroideries there are two styles, one of producing the real old Persian designs of the Muslim invaders of India, and the other a bastard importation from Germany, a formless unbeautiful thing, neither Oriental nor European. The true of Persian designs are becoming rarer and rarer, for the tourists’ “taste” is invariably for the debased potteries but what still remain of them are of a delicate and rare beauty, and poems and psalms are woven into bright silks in a hieroglyphic language of color. Hindu designs are simply a monotonous repetition of the same pattern over and over again, but the design of the Muslim artists, especially those of Persia, are full of fanciful beauty, with a world of delicate variations on the main theme of the composition. I think they are the result of a strong artistic and and creative instinct confined by the literal interpretation of the command, “Thou shalt not make any image of the likeness of anything in heaven or on the earth.” There is not actual portraiture in the Muslim designs; a butterfly in one before me has one wing pale green and the other wing a delicate creamy white lined with rose; and a pheasant in another design has a host of delicately blended hues which are certainly not “likeness of anything in heaven or earth.” But the beautifully interwoven curves and sweeping lines, never abandoned to mere extravagance but always thoroughly under the command of the artists, have a peculiar grace which forbid us to lament the stringency of the Muslim law—indeed, the very name of this species of designing, “Arabesque,” shows that it took its rise amongst the Muhammadan people.

There is a world of difference between these designs and the patterns on the old Hindu brasses of Benares. Here portraiture is no longer forbidden to the artist, and indeed, his fancy runs riot in portraiture. But here, nevertheless, the result is not the likeness of anything on the earth beneath, at any rate. Here a quaint, distorted image of the monkey god Hanuman, chased in the yellow brass, and chiseled Devas, and Gaudhavas, and Rakshasas, and all manner of celestial sylphs and infernal demons. Here are strange elephants, more like the shaggy mammoth, and horses such as are never seen except in equestrian statues. Here are strange palm trees with only one leaf, and temples that even the grotesque architecture of India could hardly reproduce. But in spite of all this exaggeration and exuberance, in spite of all this grotesque ugliness, these brasses have a peculiar beauty all their own.

Leaving the open shops and the keen-eyed native merchants, we drive away through the city of the garden of the wonderful mosques. Evening, that always falls rapidly in these tropical latitudes, was drawing on; the fire faded out of the sky—that hot, parching glow that always fills the day in India—and the vault of heaven gradually faded to a pale, transparent green, paling to yellow in the west; a few bars of crimson cloud lined with grey streaked the horizon, and the air became musical with the shrill vespers of the crickets.

The mosques loomed up into the sky with a dark, melancholy majesty; the well-cut, firm brown stone contrasting grandly with the ill-baked bricks that we had been used to in the mosques of Bengal; and the broad graceful, severe lines of the architecture standing out in strange beauty against the transparent, faintly luminous sky. There are no worshippers now in these lonely mosques that date from the greatest days of the grand Moghuls; no longer does the deep voice of the muezzin echo out on the stillness in waves of musical invocation. “There is no god but God! To prayer! For God is great!” The long rows of white-robed worshippers, with feet bare and head reverently covered, no longer bend and kneel and rise and kneel again at the name of Allah; prince and merchant and soldier and beggar all praying together side by side in the presence of Allah, who is no respecter of persons. These great days are gone, the only denizens now of the mosques are the owls and the bats; and the only prayer is that breathed by the carved inscriptions of stone, giving out with cold lips the praises of the one merciful and compassionate God in those wonderful letters of the Arabs that surpass all others in decorative beauty. It is almost with a shiver that we turn away from the desolate, stately mosque, leaving their further study and our promised visit to the fort with its underground temples to the morning.

The next morning we drove by a gradually rising spiral road to the Fort of Kalinjar, passing through arches and battlements as old as the hills themselves, with here and there new arches added by successive conquerors of India.[1]

At last, mounting to the top of the highest platform, we reach the topmost battlement, and see away down below us the broad blue tide of the Jumna, flowing southward to its union with the Ganges. To the north we see the blue line of that holy river, veiled in the morning mist, with faint rows of palm trees on its further bank. Down below us, under the precipitous walls of the fort, a narrow yellow strip of sand, bordered with withered shrubs, and here and there a native boat floating down the broad blue tide. Strange antique vessels, with high poops and prows, like the old Roman galleys, and a single lateen sail flapping its brown wings in the faint morning air. Up the river, the vast span of the Jumna bridge carries the eye to the opposite bank, where the lines of the palm trees, growing fainter and fainter in the distance, stand out in stiff rows against the sky. The silence here is complete—a silence that may be felt—in strange contrast to the myriad murmurs that generally fill an Indian picture. Even the kites and eagles that generally weave their long circles in the air are absent, but down there over the town, we can see tiny brown specks swooping and hovering in the air.

But growing heat warns us that the time for sight-seeing is drawing to a close, and returning to our carriage, we are about to drive homeward, when our coachman tells us we should not leave the fort without seeing “the tree in Hell.” We were astonished, but cross-questioning only elicited a repetition of the statement that “there was a Hell (Patala) with a tree in it,” and that we ought not to go without seeing it.[2] Our guide broke off the dialogue by saying that he would show us the mouth of the “Hell” forthwith, and that we might see for ourselves. We were conducted to what appeared to be an oblong well, but which on a nearer approach showed a narrow flight of steps descending apparently into the bowels of the earth. An odor of resinous smoke rose up, and we saw a faint gleam of flames go down below; this added to some dull smothered voices almost convinced us that we had really come to the mouth of the Pit. However, we began to descend, and were somewhat reassured to find that the smoke and the flames came from nothing worse than three or four torches, held by the black, almost naked owners of the mysterious voices. Before us opened a long, dimly-lighted corridor of virgin rock, along the slaty sides of which the torch-light gleamed and glinted; the smoke wreath curled up into the air, making it hot and dense, and almost unbreathable.

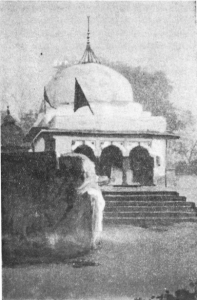

Bharadwaja Temple.[3]

Our progress along the mysterious vault commenced, escorted by the half-naked gesticulating, noisy crowd of torchbearers whose oiled bodies shone glinted in the torchlight. The passages opening upon either side sent back hollow echoes of our voices, and we began to feel that this was not the infernal regions, still the imitation was alarmingly realistic. Cold shudders ran up and down my back at the thought that we might be suddenly murdered in this dreadful cavern, and our bones left to molder in some dark vault. But as these unpleasant expectations remained unfulfilled, the interest of the new experience seized me, and we began to note the strange sights and sounds around us. From niches of this strange rock temple, dating from untold antiquity, the figures of hideous Hindu gods peered out at us, many handed, many headed monsters. Then, coming to the largest chamber, we saw the sacred trunk, a veritable tree stem springing up in the bowels of the earth. Beside it, a hideous idol of Mahadev, with garlands of withered flowers, and round it saucers of coconut oil in which burned smoky sacrificial wicks. Before the idol lay coins of many countries brought here by pious pilgrims and among these some so old that they must have dated from the days of the Moguls. The greedy priest saw our eyes fixed on them, and, without hesitation or shame he at once proposed to sell us some of the property of his god for current coin. The bargain was soon concluded, and with a deep sigh of relief we left the demoniac-looking vault and passed out to the open air. I have visited shrines and temples in many lands, but of none do I bear such a gruesome, ghostly memory of this strange Patala, this underground temple in the sunburnt Allahabad.[4]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Johnston does not name the fort in the original text, but based off of his description, it is no doubt the Fort of Kalinjar. [Tyler, R. “Fort Of Kallingur.” The Asiatic Journal. Vol. XI, No. 1 (January 1821): 16-34.]

[2] The Patalpuri Cave was located near the mouth of the Triveni well. [Tyler, R. “Fort of Kallingur.” The Asiatic Journal. Vol. XI, No. 1 (January 1821): 16-34.] It was described as a subterranean passage that contained alcoves at intervals on both sides of it, “but it was so dark, and so infested with bats, that no one venture[d] to go beyond 18 or 20 feet.” The height of the doorways of this rock-cut cave ranged from 2 feet to 5 feet, and the width from 2 feet 7 inches, to 4 feet. On the western border of this ruin were images of Buddha in situ, on narrow, dilapidated, plinths, with a few small, stone, pillars on their sides which had nothing to support. [Dey, Nundolal. “The Vikramaslia Monastery.” The Journal Of The Asiatic Society Of Bengal. Vol. V. (1909): 1-13.] As Johnston states that coachman called this place “the tree in Hell,” I suspect there is a layer of some Islamic influence at play here, as such a tree, Zaqqum, which is mentioned in the Qur’an. “Indeed, it is a tree that grows in the depths of Hell, bearing fruit like devils’ heads.” (Surah 37:64-65.)

[3] The Modern Review. Prayag Or Allahabad: A Handbook. The Modern Review Office. Calcutta, India. (1910): 91.

[4] Johnston, Charles. “In Allahabad.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) January 24, 1892.