CHOLERA

Charles Johnston

February 1890

The pariah dogs were forgotten in the sterner, depressing duties of the cholera epidemic, which came down upon Kandi Subdivision two months before its time.[1] The deeper cause, I suppose, was bacterial infection. The predisposing condition was colic, due to the eating of new rice, which has some such effect as green crab-apples have in the department of the interior. So my people began to die like flies.[2]

Certain Bengali ways made it terribly and needlessly hard to help them. The infection, bacillus, or whatever it be, was carried by subsoil water through the sandy loam of the Ganges Delta, and cropped up suddenly here and there, to disappear only with the of the greater rains. It seemed a matter of pure water, but how was one to secure that for a people who bathed in their artificial ponds, washed their clothes in them, and lastly, when all other necessities were served, filled their brass water jars and take them home to drink.

We arranged for the distribution of camphor dissolved in ether, the best thing to counteract the initial colic; and tried hard to keep at least one tank pure.[3] A deputation of the Bhadra Lok—it is always the Bhadra Lok—came to me, asking me to set a police guard about a certain pond from which they drew their drinking water, to keep it from pollution; for cholera is always spread by bad drinking water. This I did—in part by my own wish for a trustworthy domestic supply.[4] It was a pretty temple pond, dotted with round green leaves of crimson water-lilies, whereon certain sharp-beaked water-hens with toes, miraculously skated about in search of beetles.

A second proclamation was issued, in high Bengali, similar to the Proclamation of the Dogs, the rhetorical flourishes being added by my head clerk, a wise, sympathetic fellow with an Aryan name and a Semitic nose; and I set four policemen to watch the pond day and night, bidding them arrest, and bring to me instantly, whoever presumed to put so much as an ungodly toe into the proclaimed water.

So my pani-wala with his skin water-cask drew water in peace, as did the people of the town. Yet I afterwards learned, by subterranean ways, that the very gentlemen in tussore silk frock-coats and fancy turbans, who had come with salaams and lamentable petitions, were bribing my rascally policemen to let them bathe their unhallowed carcasses in my, and their, drinking water. Such a thing, my masters, is ancient custom; such a thing is the guile of mankind, lined with dire stupidity. I had those Bengali gentlemen up before me in full court, stood them in a row like malefactors, and from the height of the bench told them home truths in their suffering mother-tongue until they winced again. For the time they desisted, but I have a fancy that, when Soshi Babu came back with shining morning face, all went on as before.[5]

BILIOUS AS A 40-YEAR-OLD HEMORRHOID.

In a letter to her family in early February Vera writes: “Charley has become as bilious as a 40-year-old hemorrhoid. He curses India and wants to leave at the first opportunity before we starve to death.”[6] The Race Week at Berhampore (February 11-February 15, 18901) which culminated with the Race Ball, was a welcomed break.[7] “[The Nawab] had also an aigret of colored diamonds, pink and orange and rosy, which I once came near annexing, when he left his fez in the supper room after the Race Ball,” Johnston writes, “I bethought me, however, that such stones would be identified, and restored them. The Nawab lost three big diamonds the same night, but I know nothing of them.[8] (This was something of a habit for the Nawab. While visiting Lord Dufferin in March 1888, the Nawab lost a gold locket containing a miniature portrait of Queen Victoria, valued at Rs. 4,000, that the British Government gifted him.)[9] When Johnston returned to Kandi, he went back to the quotidian tasks of administration while suffering from the residual effects of malaria. His frustration being transparent in the letters he wrote to Vera Petrovna in late February 25, 1890:

(February 25, 1890) My dear Mom, it’s pretty disgusting here—but I think Verochka has already told you everything, so I need not say anymore. Damn you “bright India,” as Elena Petrovna says; there is no place worse in the world. I’ll finish the translation [of Rosanchik] now. I hope it will be translated well enough. Vera likes it. Elena Petrovna says that the Hindu people are very bright and strong-hearted, but that is just nonsense and “flintiflushi.” They are the biggest fools and idiots in the world. Ah![10]

(February 27, 1890) I have a lot of plans and ideas in my head, but I cannot write in this damned hell. Writing a letter is a burden. It’s just a disaster. I am surprised that Elena Petrovna could work in this place for nearly eight years.[11]

THE COMMISSIONER

Charles Johnston

March 1890

My stately visitor, Alexander Smith, the Commissioner, was a huge, tired gentleman, who had given a long life, and a great life, to India, and had but the dregs of it left. He was one of the bricks in the altar of sacrifice.

Smith camped in the great mango tope, whence we went forth together to review my dominions. We talked, he as master, I as learner, of such things as lie close to the hearts of all Covenanted-Walas: ryots and crops, assessments and tenures, criminal and civil law; and always his thought was keenest, his heart most tender, for the fate and wealth of the lowly, the real beneficiaries of England’s quiet rule. Save for the spell of cholera, which had been very destructive, I had a good account to render of my people. We had a session with the books of with so many the court: so many thefts, convictions; assaults, simple or aggravated; lurking house-trespass…Accounts, too, we went over together: land-taxes, excise-levies, sales of opium, gunja, stamps, fees of one kind and another, making up the receipts; while on the side of disbursements stood the salary of the Umbrella of the Poor and the pay of his subordinates, payments for government buildings and the like, and, finally, remittances of hard-earned balances to the District Treasury.

The kind old man slowly, rather absently, but with entire faithfulness, went over these accounts and signed the books. Then we went together to the jail, of which the writer of these things was governor. I was not inordinately vain over that mud jail with its thatched shed, nor yet was I cast down. For a magnificent new prison with huge walls of brick was being built a hundred yards away, in response to the importunities of Govinda Babu. But I liked my little mud jail best; and so, I think, did my five prisoners. Indeed, we all held it in such affection that, after my tame desperadoes had been reviewed, I patted the low clay wall, and said to Smith—“It is very considerate of the prisoners not to kick the wall down and walk away!”

By the way, naked toes may have had something to do with their forbearance, yet my obligation to them remained. Well, when we had examined all these things and found them to be very good, pending dinner in camp the great man returned to my office to report on what he had seen to that even greater man, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal. He wrote a line or two about this and that, spoke of crops and taxes, and then bethought him to add, in conclusion, a word or two about the jail. But words come not easily to tired souls and out-worn years; so, finally, smiling to himself, he wrote, with softly creaking quill:—“It is very considerate—of the prisoners—not to kick down the wall—and walk away.”[12]

CUTTACK

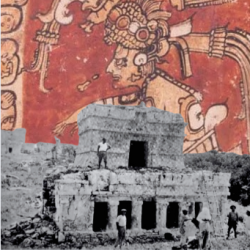

In early March, Charley was transferred to the Sadr Station of Cuttack in the District of Orissa, “not far from the famous shrine of the Jagannath,” to fill the position of Assistant Magistrate.[13]

“View from the east towards the Jagannath Temple, Puri, with the bazaar in the foreground.”[14]

As Johnston was preparing for his next post, the people of Kandi were preparing for their Rain Festival. There was once a holy man in Kandi by the name of Kameswar Brahmachari who lived on the eastern bank of the Mayurakshi River at a place called Hat Rudragunge. Kameswar possessed the images of two deities named Rudradeva and Kala Rudradeva. One day a nobleman who suffered from severe colic pain, Rudra Kantha (Ganga Govind Singh’s ancestor,) met Kameswar while walking along the Mayurakshi River. Humbled by the holy man and his idols, Rudra Kantha offered his services to Kameswar, and became a faithful adherent. Taking pity on Rudra Kantha, Kameswar cured him of the colic pain. When the time eventually came for the holy mendicant to die, he gave the two idols Rudradeva and Kala Rudradeva to Rudra Kantha and made him promise that he should bring the two idols to Kameswar’s resting place every year, and ritually bathe them in the Ganges. The Zamindar of Pargana Fatteh Singh, being powerful force in that part of the country, confiscated the two idols from Rudra Kantha and placed them in a temple he built in a village named Rupapur. In accordance with the dying wish of Kameswar, however, the two idols were removed from them temple once a year, and ritually purified in the manner directed by the holy man. This was in the latter half of the Bengali month of Chaitra (roughly corresponding to March 23-April 23 in the Gregorian calendar.) Like the Doljatra, which occurred at roughly the same time, this puja involved specific rites in the river to invoke blessings. The idols of Rudradeva and Kala Rudradeva became local water gods and appealed to preceding the rains.[15]

In April Johnston was promoted, and “vested with the powers of a Collector.”[16] With his own health in decline, and Vera showing early signs of Chronic Valvular Disease, the Johnstons decided it was time to leave India.[17] In May Johnston made an appeal to return to England. On June 7, 1890, he was granted special leave for six months, “with effect from such date as he may avail himself of it.”[18]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] The Cholera season in Murshidabad began sometime between April and May. [Cunningham, David Douglas; Lewis, Timothy Richards. Cholera In Relation To Certain Physical Phenomena. Office Of The Superintendent Of Government Printing. Calcutta, India. (1878): 61.]

[2] The Murshidabad District ranked below the general health standard of Bengal. Stagnant pools, which formed by the Bhagirathi during the dry season, were “a perennial source of malaria,” and cholera was rarely absent from the city and suburbs. It was not only the trading emporium of Kasimbazar that had been abandoned, but several flourishing villages were also “absolutely depopulated by malarious fever.” [Hunter, W. W. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India Vol. X. Trübner & Co. London, England (1886): 31.]

[3] Babu Nafar Das Roy, a member of the Adhi Bhoutic Bhratri, also claimed minor success in treating the sick with mesmerized water, while other members of the Branch administered similar homeopathic treatments to 75 patients. Like Tukarum Tatya’s clinic in Bombay, they distributed medicine free of cost. [“Branches Of The Theosophical Society—Indian.“ General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 68-77.]

[4] The rampant spread of disease was taking a toll on the psychological ecosystem of the people. The Bhadra Lok, influenced by European medico-topographical surveys, and the miasmatic-theory of disease, were adopting a world-view of environmental determinism. Many came to believe that they were a “dying race” destined for extinction by cholera and malaria. [Mukherjee, Sujata. Environmental Thoughts and Malaria in Colonial Bengal: A Study in Social Response. Economic and Political Weekly. Vol. XLIII, No. 12/13 (March 22-April 4, 2008): 54-61.]

[5] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273; Johnston, Charles. “Fuller Liberty For India.” The North American Review. Vol. CCIX., No. 763 (June 1919): 772-780.

[6] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” February 3, 1890, g, Kandi, India, entry.

[7] “Fixtures For The Week.” Civil & Military Gazette, (Lahore, Pakistan) February 8, 1890; “Fixtures For The Week.” Civil & Military Gazette, (Lahore, Pakistan) February 14, 1890.

[8] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[9] Fazl Rubbee wrote to a Calcutta newspaper in May 1888: “His Highness has lost […] the gold locket surmounted with brilliants, containing a miniature portrait of Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen Empress, worth Rs. 4,000, which had very kindly been given to him by Government, in lieu of the ordinary khilut that was intended to be conferred upon His Highness in connection with his installation as ‘Nawab Bahadur of Murshidabad.’ This locket was very unfortunately lost in the mouth of March last, when His Highness went down to Calcutta to attend the meeting that was held at the Town Hall in honour of His Excellency the Viceroy.” [“The Nawab of Murshedabad.” The Bangalore Spectator. (Bangalore, India) May 15, 1888.] This meeting was a farewell reception held on March 22, 1888, at the Town Hall. [“The Dufferin Demonstration.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) March 27, 1888.]

[10] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” February 25, 1890, Kandi, India, entry.

[11] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” February 27, 1890, Kandi, India, entry.

[12] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.

[13] “[Page 4.]” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) March 4, 1890; “By Way Of Introduction.” The North American Review. Vol. CCXXV, No. 842 (April 1928): 1-3.

[14] Photograph of the Jagannatha Temple, Puri from the Archaeological Survey of India Collections, taken by William Henry Cornish in c.1892.

[15] Mitra, C.C. “The Rain Ceremony In Murshidabad District.” The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Vol. LXVII, No. 1. (1898): 25-34.

[16] “Government Notification.” The Hindoo Patriot. (Calcutta, India.) April 7, 1890.

[17] Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania (State). Death Certificates, 1906-1968; Certificate Number Range: 085001-088000.

[18] “Orders by the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal by High Court, Government Treasury, &c.” The Calcutta Gazette. (Calcutta, India) June 11, 1890.