ROSANCHIK

Vera Johnston.

January 6 & January 19, 1890.

(January 6, 1890) There is a little portrait of mother and the Solovyev album with all of you on the tables. Personally, between us, I often think that Valya had nothing more to do since he began to wither, but his consciousness, his soul, wanted to stay for us all, and did so while vitality remained in his body. When he was very small, his soul was not taxed, and was not very impressionable, and he never got sick. Then, immediately, when he was around 14 or 15, without reading, without education, without effort, a great mind, absent even in those far older, was awakened. He had an impact on all of us. Without words, but through his spirit, his mere presence lifted us all, and flashed as an example to many strangers. His pure and lofty soul, finding no reason to remain on earth, decided to leave. I know that his death affected all of us, but as for myself, I find the effects his death have influenced me completely—I have grown wiser, and begin, now, to understand the nature of life and death. I am not afraid of death in the least. I have learned to despise pain. I write all this with tears, but not tears of grief and sadness, but because we meet raw, emotional tenderness, and profound joy, with tears.[1]

(January 19, 1890) Charley sits next to me translating Rosanchik. I’m tired of stupid India—it’s worse than a bitter radish.[2]

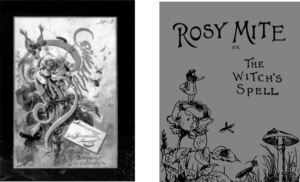

Rosanchik was a children’s story written by Vera Petrovna in 1888, shortly after the death of her son, Valya.[3] It was first published in Russia in early 1889.[4] Some copy of this book, whether a manuscript or in its published form, reached the Johnstons while in India, for in a letter to her mother in January 1890, Vera writes: “Charley sits next to me translating Rosanchik. I’m tired of stupid India—it’s worse than a bitter radish.”[5] Around Christmas 1890, after the Johnstons returned to England, Countess Wachtmeister approached Vera and expressed her admiration for Rosanchik. Wachtmeister explained that she desired “to print and sell Theosophical book[s] for children,” and suggested publishing it with the Theosophical Society. Vera Petrovna would keep all of the profits, and the Theosophical Publishing Society would collect the material cost of printing. Vera wrote a letter to her mother urging her to consider its publication in English. The only obstacle she foresaw was that it was dedicated to the Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, the daughter of Czar Alexander III.[6] (It was ultimately decided that the book would be published without the dedication.)[7]

In the summer of 1894, Vera met with Alfred Joseph Faulding (1853-1916,) a book publisher and Theosophist.[8] He agreed to publish 300 copies of Rosanchik with Truslove & Hanson, with the potential for more editions. Vera Petrovna would receive nothing for the first thousand, and 10% for the second. “The conditions are good,” Vera states, “as the company is businesslike, and assures us that it will sell at least 2,500 copies.” The publishers wanted to sell Rosanchik for 2 shillings and 6 pence. To reduce the cost of printing, the size of the book was reduced, and the illustrations were colorless. Truslove & Hanson also decided that it would be unwise to mention that it was a translation from Russian, and to let readers “think it [was originally] written in English.”[9] Rosanchik, published in English under the title Rosy Mite, hit the shelves in time for Christmas 1894.[10] It was illustrated by “T. Pym” (pseudonym of Clara Creed.)[11] A review in Lucifer for Rosy Mite stated: “Such a kindly spirit of good fellowship with all that lives speaks throughout the pages of this dainty little story.”[12]

(Left) Cover of Rosanchik (1889.) (Right) Cover of Rosy Mite (1894.)

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” January 6, 1890 g./December 25, 1889 j., Kandi, India, entry.

[2] V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” January 19, 1890 [g.], Kandi , India, entry.

[3] Bogdanovich, Olga. Blavatsky And Odessa. Odessa House Museum. Odessa, Ukraine. (2006): Chapter IV.

[4] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. Rosanchik. Izdanie A. F. Devriena. Saint Petersburg, Russia. (1889.)

[5] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [January 19, 1890 [g.], Kandi , India, entry.]

[6] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [j.] December 16, 1890 [g.] December 28, 1890, London, England, entry.]

[7] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [j.] January 11, 1890/1891 [g.] January 23, 1891, London, England, entry.]

[8] Alfred Joseph Faulding. [Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2007. Original data: General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England: General Register Office. General Register Office; United Kingdom; Volume: 1b; Page: 663.]

[9] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” [j.] August 15, 1894, [g.] [August 27, 1894. 17 Avenue Road, London, England, entry.]

[g.] January 23, 1891, London, England, entry.]

[10] Jelihovsky, Vera Petrovna. Rosy Mite or The Witch’s Spell. Truslove And Hanson. London, England. (1894.)

[11] Gonzalez, Eugenia. “’I Sometimes Think She Is A Spy On All My Actions’: Dolls, Girls, And Disciplinary Surveillance In The Nineteenth-Century Doll Tale.” Children’s Literature. Vol. XXXIX. (2011): 33-57.

[12] H.T.E. “Review: Rosy Mite: Or The Witch’s Spell.” Lucifer. Vol. XV, No. 87. (November 15, 1894): 252.