The Shaman’s Secrets.

Ever on the lookout for occult phenomena, and hungering after sights, one of the most interesting things that Blavatsky had seen in India, was the phenomena produced by a poor traveling Bikshu (monks.) She was taken to visit the pilgrims by a Buddhist friend, a mystical gentleman born in Kashmir, of Kutchi parents, but a Buddha-Lamaist by conversion, and who generally resided at Lhasa.

“Why carry about this bunch of dead plants?” inquired one of the Bikshuni, a tall, emaciated, and elderly woman, pointing to a large nosegay of beautiful, fresh, and fragrant flowers in Blavatsky’s hands.

“Dead?” Blavatsky asked, inquiringly. “Why they just have been gathered in the garden?”

“And yet, they are dead,” the Bikshuni gravely answered. “To be born in this world, is this not death? See, how these herbs look when alive in the world of eternal light, in the gardens of our blessed Foh?”

Without moving from the place where she was sitting on the ground, the woman took a flower from the bunch, laid it in her lap, and began to draw together, by large handfuls, invisible material from the surrounding atmosphere. Then a very (very) faint nodule of vapor was seen, and this slowly took shape and color, until, poised in mid-air, appeared a copy of the bloom Blavatsky had given her. Faithful to the last tint and the last petal, and lying on its side like the original, but a thousand times more gorgeous in hue and exquisite in beauty. Flower after flower to the minutest herb was then reproduced and made to vanish, reappearing at Blavatsky’s desire—at her simple thought. Having selected a full-blown rose, Blavatsky held it at arm’s length, and in a few minutes her arm, hand, and the flower, perfect in every detail, appeared reflected in the vacant space, about two yards from where she sat. While the flower seemed immeasurably beautified and as ethereal as the other spirit flowers, the arm and hand appeared like a mere reflection in a looking glass, even to a large spot on the forearm, left on it by a piece of damp earth that had stuck to one of the roots. Such manifestations were relatively new to her, but she eventually learned the secrets of this manifestation.[1]

It was 1855— Blavatsky was in India, traveling from place to place, never telling anyone that she was Russian—letting them assume what they liked in this regard.[2] “No Englishman ever believes any good of a Russian. They think we are all liars,” she thought. “I don’t understand how these Englishmen can be so very sure of their superiority, and at the same time in such terror of our invading India.”[3] The Crimean War was drawing to a close, and it was unwise to reveal her Russian roots. Tsar Nicholas I died in the early days of 1855, and Blavatsky gave the matter some thought as she traversed the Indian subcontinent. “He sacrificed his life to Russia, that his son and heir might end the disastrous Crimean War,” Blavatsky thought, believing that the Tsar forced his physician, Dr. Mandt, to administer the poison needed to commit suicide. “His own sense of dignity and pride prevented him from doing so himself.”[4]

Though India was under the control of the British at the time, it was not under the control of the British Government. The East India Company, a British corporation, won control of India from the Mughal Empire with their private army during the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Nearly a hundred years later and there was growing unrest in the land, owing to several factors. First, there was the growing tendency of the British power to absorb the Native States (whenever a disputed succession offered a pretext.) Then there was the prophecy “that the rule of the East India Company would end a hundred years after Plassey.” The third reason, potent but less defined, was that the genius of India felt rebuked by British dominance and resented as oppression.[5] Blavatsky’s impressions of colonial rule were not favorable. The Indians were made to feel as an “inferior race” by the English, and as she experienced firsthand, the English believed that the “inferior races” existed “only to serve the ends of the English.”[6]

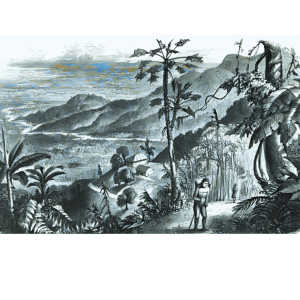

The trek was dangerous to say the least. In the middle of 1855, serious disturbances broke out amongst the tribes of the Santhal Parganas, and for a short time the whole country was in the hands of the insurgents. It became necessary to place a considerable force in the field to put down the outbreak.[7] Nevertheless, she pressed onward to the Darjeeling Hills, where she intended to visit Tibet and Nepal (and meet with Master Morya.)[8]

In 1833 the East India Company lost its monopoly rights in the tea trade with China. By 1840 a plan was formulated to grow tea in India, Darjeeling proving the most successful environment. European planters soon acquired large stretches of the Himalayan hillside and converted them into plantations. Ancient paths were renamed as roads that connected to the Hill Cart Road. The traffic on these roads was heavy with carts and pack animals that brought fruit and produce from Nepal, and wool and salt from Tibet. It also carried laborers looking for work, the migrations of which created hostility between the East India Company and the neighboring Himalayan kingdoms that culminated in open hostilities by 1849. This resulted in the British exploiting the incident as a pretext to annex 640 square miles of territory from Sikkim. In 1850 Darjeeling became a municipality under the control of the East India Company which administered the territory from their Darjeeling Hill Station.[9] Blavatsky could see it, for the Station occupied a narrow ridge that divided into two spurs, descending steeply to the bed of the Rangeet River (whose course carried the eye to the base of the great snowy mountains.) The ridge itself was very narrow at the top, along which most of the houses were perched.[10]

Punkabaree Bungalow.[11]

Blavatsky was unsuccessful in her attempt at crossing the cane-bridge, for she was apprehended by British authorities. She was taken to Punkabaree to speak with Lieutenant Charles Murray, commander of the Sebundy Sappers And Miners.[12] As military command of the Frontier District, Lt. Murray was given strict orders to permit no European to cross the Rangeet, “as they would be almost sure of being murdered by wild the wild tribes in that country.” Blavatsky was very angry but in vain. She stayed with Lt. Murray and his wife for about a month before, realizing her plan was defeated, retreated down the mountain.[13]

Lahore.[14]

In Lahore Blavatsky was “taken over” by Ernst Külwein, the brother of her childhood governess, Antonia.[15] In association with his two associates, the Nemetsky brothers, he laid out a journey to the East on his own account with certain designs.[16] Ernst was a positivist and rather prided himself on this anti-philosophical neologism. He learned from some old Russian missionary of a particular “miracle of incarnation” performed by the Tibetan Lamas similar to the one Abbé Huc described in Recollections Of A Journey Through Tartary, Thibet, And China.[17] It had been, for years, the desire of Ernst to expose the “great heathen” jugglery, as he expressed it. Evidently Blavatsky’s father, Colonel Hahn, tasked Ernst with bringing back his errant daughter if possible. It was not possible. The four companions, instead, traveled together for a time to Kashmir.

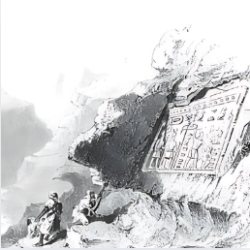

“Stone With Mystic Sentence.”[18]

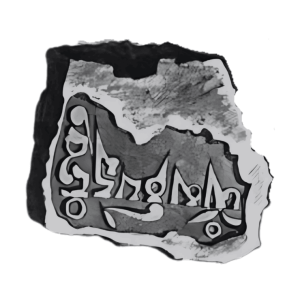

Ernst updated Blavatsky on gossip from home, and the sad news of Antonia’s passing in April 1850. Reaching into her cluttered satchel, she clutched her talisman known as an Ayu. It was given to her by a venerable Heloung (high priest,) when Blavatsky, Vera, and Antonia stayed in Prince Tyumen’s Kalmuck camp. The simple carnelian stone said to be endowed with very mysterious properties, was engraved with a triangle inside which “a few mystical words” were written.[19] It had sentimental value, too, for it was gifted to her just days after her mother’s funeral.[20]

Along the way, they encountered a very mysterious Tartar Shaman who agreed to be their guide to Kashmir and onward to Leh in Ladakh. He did not speak a word of English and only a few words of Russian, and yet he managed to converse with them and proved of great service. Blavatsky, who along her travels learned a bit about the Shamans, would explain it was “spirit-worship, or belief in the immortality of the souls,” and that the latter were “still the same men they were on earth.” Though their bodies had lost their objective form and had “exchanged his physical for a spiritual nature.”[21] Indeed, spirit communication had a long history in the Russian Empire. “In the rural districts it is alleged that every village entertains its pantheon of spectral agencies,” wrote Blavatsky’s contemporary, E.H. Britten, “whilst the Shamans, or prophet priests of Siberia, have proverbially obtained for their wonder-working powers a worldwide celebrity.”[22]

Leh, Ladakh.[23]

As for modern Western Spiritualism, it, too, had made inroads into the Russian Empire. One of the first Russian scholars to seriously explore the subject was Mikhail Vasilyevich Ostrogradsky, a mathematician who belonged to the Academy of Sciences. After some experiments, he became a convinced Spiritualist. He tried in vain to attract the attention of his colleagues in the Academy to his new convictions, founded on the facts that he had accumulated. The scientific men “considered him a lunatic,” and refused to submit to his request for an impartial investigation of the matter. It was not possible in Russia at this time for a learned man to use the Press to ventilate convictions that were regarded as strange to the masses. By 1852 the first reports about the “strange phenomena which had manifested themselves in America” reached Russia.[24] These first rumors about Spiritualism (which did not yet have a name,) came to Russia in hot, troubled times, for it was during the period coinciding with The Crimean War (1853-1856.)[25] Blavatsky sister, Vera Petrovna, who dabbled in table-turning, would say of this time: “We completely abandoned our spiritualistic pursuits. It was a very difficult time for all Russians. Our military affairs weighed heavily on everyone’s souls; everything ahead seemed gloomy and foggy, and in this impenetrable fog our glorious, tortured Sevastopol—the Russian martyr for all the sins of all Europe.”[26]

Having learned that some in their party were Russians, the Shaman had imagined that their protection was all-powerful, and might enable him to safely find his way back to his home in Siberia. For some unknown reason, he fled his home twenty years earlier, via Khyagt and the great Gobi Desert, to the Kokand Khanate, the land of the Chagatai Tajiks. With such an interested object in view, Blavatsky’s party believed they were safe under his guard.

The companions had formed the unwise plan of penetrating into Tibet using various disguises. None of them, however, spoke the native language. Ernst, however, having picked up some Kazan Tartar, certainly thought he did.

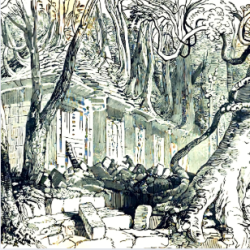

About four days into the journey from Islamabad, they stopped for a few days’ rest at an insignificant mud village whose only redeeming feature was its magnificent lake. The Nemetsky brothers had temporarily separated from Blavatsky and Ernst, and the village was to be their place of meeting. It was here where their Shaman guide explained that a large party of Lamaic “Saints” on a pilgrimage to various shrines, had taken up their abode in an old cave temple where they established a temporary Vihara. He added that, as the “Three Honorable Ones” were said to travel along with them, the holy Bikshu were capable of producing the greatest miracles. (Blavatsky was familiar with Tibetan Buddhism from stories that her grandfather told, as well as her own experience in the Kalmyk Ulus.)[27] Ernst, excited at the prospect of “exposing this humbug of the ages,” went at once to pay them a visit. From that moment, the most friendly relations were established between the two camps. The Vihar was in a secluded (and most romantic spot,) secured against all intrusion. Despite the effusive attentions, presents, and protestations of Ernst, the Chief, who was Pase-Buddha (an ascetic of great sanctity,) declined to exhibit the phenomenon of the “incarnation” until a certain talisman was exhibited. The same talisman, as luck would have it, that Blavatsky had in her possession—the Ayu that Prince Tyumen’s Heloung had gifted her. Upon seeing this, preparations were at once made, and an infant of three or four months was procured from its mother—a poor woman of the neighborhood. First, an oath was exacted of Ernst that he would not divulge what he might see or hear, for the space of seven years.[28]

Several days passed before everything was ready. Meanwhile, at the bidding of a Bikshu, ghastly faces were made to peep at them from out of the glassy bosom of the lake, as they sat at the door of the Vihar, upon the bank. One of these was the countenance of Antonia. The sight initially affected Ernst, but he called his skepticism to his aid and quieted himself with pareidolic theories of cloud-shadows, reflections of tree-branches, etc. On the appointed afternoon, the baby was brought to the Vihara and left in the vestibule or reception-room (as Ernst could go no further into the temporary sanctuary.) The child was then placed on a bit of carpet in the middle of the floor, and everyone not belonging to the party was sent away. Two “mendicants” were placed at the entrance to keep out intruders. Then all the Lamas sat on the floor with their backs against the granite walls, so that each was separated from the child by a space of ten feet.

“Election Of A Living Buddha.”[29]

The Pase-Buddha, having had a square piece of leather spread for him by the desservant, sat at the farthest corner. Alone, Ernst placed himself close by the infant and watched every movement with intense interest. The only condition exacted of the visitors was that they should preserve a strict silence, and patiently wait for further developments. A bright sunlight streamed through the open door. Gradually the Pase-Buddha fell into a state of profound meditation, while the others, after a brief sotto voce invocation, became suddenly silent, and looked as if they were completely petrified. It was oppressively still, and the crowing of the child was the only sound that could be heard. After they had sat there a few moments, the movements of the infant’s limbs suddenly stopped, and his body appeared to become rigid. Ernst intently watched every motion, and both he and Blavatsky, by a rapid glance, became satisfied that all present were sitting motionless. The Pase-Buddha, with his gaze fixed upon the ground, did not even look at the infant. Pale and motionless, he seemed like a bronze statue of a Talapoin in meditation rather than a living being. Suddenly, to their great consternation, they saw the child violently jerk into a sitting posture! A few more jerks, and then, like an automaton set in motion by concealed wires, the baby, just sixteen weeks old, stood upon his feet! Not a hand had been outstretched, not a motion made, nor a word spoken—and yet, here was a baby standing erect and firm as a man! After a minute or two of hesitation, the baby turned his head and looked at Ernst with an expression of intelligence that was simply awful! It sent a chill through right through him. Ernst pinched his hands and bit his lips until the blood almost came, to make sure that he was not dreaming. This was only the beginning. The baby made two steps toward Ernst, resumed his sitting posture, and, without removing his eyes from Ernst, repeated, sentence by sentence in Tibetan, the very words that Ernst had been told in advance were commonly spoken at the incarnations of Buddha, “I am Buddha; I am the old Lama; I am his spirit in a new body,” etc. Ernst felt a real terror; his hair rose upon his head, and his blood ran cold. It was as if the spirit of the Pase-Buddha had entered the little body, and was looking at Ernst through the transparent mask of the baby’s face. He felt his brain growing dizzy. The infant reached toward him and laid his little hand upon his own. It felt to Ernst as though he had been touched by a hot coal—unable to bear the scene any longer, he covered his face with his hands. It was only an instant, but when he removed them, the crowing baby returned to his normal state again. A moment later the baby was upon his back, setting up a fretful cry. The Pase-Buddha had resumed his normal condition, and a conversation ensued.

“What would have happened,” Ernst asked, through the Shaman, “if, while the infant was speaking, in a moment of insane fright, at the thought of its being the ‘Devil,’ I had killed it?”

“If the blow had not been instantly fatal,” the Pase-Buddha replied, “the child alone would have been killed.”

“But,” Ernst continued, “suppose that it had been as swift as a lightning flash?”

“In such case, you would have killed me also.”

The journey soon continued, but Ernst, prostrated with fever, did not dream of leaving his miserable village near Leh. He was forced to return to Lahore via Kashmir. The Nemetsky brothers managed to walk sixteen miles into the “weird land of Eastern Bod” before calling it quits and very politely brought back to the frontier. Blavatsky and the Shaman, alone, ventured forth, and the day soon arrived when her talisman “spoke.” It was during the most critical hours of her life—at a time when the vagabond nature of a traveler had carried her to far-off lands, “where neither civilization is known, nor security can be guaranteed for one hour.” For two months she lived in a yourta (Tartar tent) with what seemed an entire caravan of people. One afternoon, as every man and woman had left the yourta to witness the ceremony of the Lamaic exorcism of an ada čidkür (evil spirit) that was accused of breaking (and spiriting away) every bit of furniture and earthenware of a family that lived two miles away.[30] The Shaman, who had become her only protector in those dreary deserts, was reminded of his promise to guide her. He sighed and hesitated, but, after a short silence, left his place on the sheepskin. Going outside, he placed a dried-up goat’s head with its prominent horns over a wooden peg, and then lowering the felt curtain of the tent, remarked that now no living person would venture in, for the goat’s head indicated that he “was at work.”

After that, placing his hand in his bosom, he withdrew a little stone, about the size of a walnut, and, carefully unwrapping it, proceeded to swallow it. Soon his limbs stiffened, and his body became rigid, eventually falling to the ground as cold and motionless as a corpse. Except for the slight twitching of his lips at every question asked, the scene would have been dreadful—or embarrassing at the very least. The sun was setting and had it not been for the dying embers flickering at the center of the tent, complete darkness would have been added to the oppressive silence that reigned. Blavatsky had lived in the prairies of the Wild West, and in the boundless steppes of Astrakhan in Southern Russia, but nothing could compare with the silence at sunset on the sandy deserts of Mongolia. Yet, there she was—alone with what looked no better than a corpse lying on the ground. Fortunately, this state did not last long.

“Mahandu!” uttered a voice. It seemed as though it had come from the bowels of the earth on which the Shaman was prostrated. “Peace be with you…what would you have me do for you?”

Startling as the fact seemed, Blavatsky was quite prepared for it, for she had seen other Shamans pass through similar performances.

“Whoever you are,” pronounced Blavatsky mentally, “go to Ernst, and try to bring that person’s thought here. See what that other party does, and tell Gospoja Popesco what we are doing and how situated.”

“I am there,” answered the same voice. “The old lady is sitting in the garden…she is putting on her spectacles and reading a letter.”

“The contents of it, and hasten,” Blavatsky quickly ordered while preparing notebook and pencil. The contents were given slowly, as if, while dictating, the invisible presence desired to afford her time to put down the words phonetically, for she recognized the Wallachian language of which we know nothing beyond the ability to recognize it. In such a way a whole page was filled.

“Look west…toward the third pole of the yourta,” pronounced the Tartar Shaman in his normal voice (though it sounded hollow as if coming from afar.) “Her thought is here.”

Then, with a convulsive jerk, the upper portion of the Shaman’s body was raised, and his head fell heavily on Blavatsky’s feet (which he clutched with both his hands.) The position was becoming less and less attractive, but curiosity, she learned, was a good ally to courage. Standing in the west corner was the life-like but misty, flickering, unsteady form of Gospoja Popesco. This dear old friend, a Wallachian lad, was a mystic by disposition (even if she did not admit it.)

“Her thought is here, but her body is lying unconscious. We could not bring her here otherwise,” said the voice.

Blavatsky addressed and supplicated the apparition to answer, but it was in vain. The features moved, and the form gesticulated as if in fear and agony, but no sound broke forth from her shadowy lips; only she imagined—perchance it was a fancy—hearing as if from a long distance the Rumanian words, “Nu se poate face.” (It cannot be done.)

For over two hours, Blavatsky was given the most substantial, unequivocal proof that the Shaman’s astral soul was traveling at her bidding. (Ten months later Blavatsky would receive a letter from Gospoja Popesco further corroborating what had transpired.) Blavatsky’s experiment was proved still better. She had directed the Shaman’s inner ego to her friend, a Kutchi from Lhasa who traveled constantly to British India and back. She knew that he was apprised of her critical situation in the desert—because a few hours later there came help, and they were rescued by a party of twenty-five horsemen who had been directed by their chief to find them at the place where they were (and which no living man endowed with common powers could have known.) The chief of this escort was a Shaberon, an “adept” whom Blavatsky had never seen before, nor did she after that, for he never left his soumay (lamasery,) and she could have no access to it. But he was a personal friend of the Kutchi.[31]

SOURCES:

[1] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 609-610.

[2] Sinnett, Alfred Percy. The Letters Of H. P. Blavatsky To A. P. Sinnett And Other Miscellaneous Letters. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. London, England. (1925): 151.

[3] Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part I.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. V, No. 12 (April 1900): 221-225.

[4] Blavatsky, H.P. “The Assassination of the Czar.” The Pioneer. (Allahabad, India) April 9, 1881.

[5] Johnston, Charles. “What The Theosophical Society Is Not.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. VI, No. 1. (July 1908): 22-28; Johnston, Charles. “The English In India.” The North American Review. Vol. CLXXXIX, No. 642 (May, 1909): 695- 707; Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXXXVIII, No. 6. (December, 1926): 848-856.

[6] Johnston, Charles. “Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Part III.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI, No. 2 (June 1900): 22-26

[7] Cardew, Francis Gordon. A Sketch Of The Services Of The Bengal Native Army To The Year 1895. Offices Of The Superintendent Of Government Printing. (1903): 258.

[8] H. S. O. “Traces Of H. P. B.” The Theosophist. Vol. XIV, No. 7 (April 1893): 429-431.

[9] Pradhan, Queenie. Empire In The Hills: Simla, Darjeeling, Ootacamund, And Mount Abu, 1820–1920. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2017): 118-119; Shneiderman, Sara; Middleton, Townsend. “Introduction: Reconsidering Darjeeling.” In (eds.) Middleton, Townsend; Shneiderman, Sara. Darjeeling Reconsidered: Histories, Politics, Environments. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2018): 1–23; Sharma, Jayeeta. “Himalayan Darjeeling And Mountain Histories Of Labour And Mobility.” In (eds.) Middleton, Townsend; Shneiderman, Sara. Darjeeling Reconsidered: Histories, Politics, Environments. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2018): 80–81; Lamb, Alastair. British India And Tibet, 1766–1910. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London, England. (2019): 71; Bhattacharya, Nandini. “Imperial Sanctuaries: The Hill Stations Of Colonial South Asia.” In (eds.) Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Framke, Maria. Routledge Handbook Of The History Of Colonialism In South Asia. Routledge. London, England. (2022): 319-330.

[10] Hooker, Joseph Dalton. Himalayan Journals: Vol. I. John Murray. London, England. (1854): 118, 142.

[11] Hooker, Joseph Dalton. Himalayan Journals: Vol. I. John Murray. London, England. (1854): 105.

[12] Lieutenant Charles Murray, 70th Bengal Infantry, led the “Sebundy Sappers And Miners” in Darjeeling in 1855. It would appear that by 1856 he was stationed in Kathmandu, Nepal, as the Resident’s Escort. [Wray, T.W. Bombay Calendar And Almanac For 1855. The Times’ Press. Bombay, India. (1855): 230; Wray, T.W. Bombay Calendar And Almanac For 1856. The Times’ Press. Bombay, India. (1856): 224.]

[13] H. S. O. “Traces Of H. P. B.” The Theosophist. Vol. XIV, No. 7 (April 1893): 429-431.

[14] Seeley. Church Missionary Tracts No. 25: The Punjab Mission At Amritsar. Seeley, Jackson, And Halliday. London, England. (1852): 13.

[15] Sinnett writes: “During her travels in India in 1856, she was overtaken at Lahore by a German gentleman known to her father, who, in association with two friends, having laid out a journey in the East on his own account, with a mystic purpose in view, in reference to which fate did not grant him the success that attended Mme. Blavatsky’s efforts,— had been asked by Colonel Hahn to try if he could find his errant daughter […] In reference to the journey in the course of which the Russian travelers witnessed the transaction at the Buddhist monastery, Mme. Blavatsky writes:—’Two of them, the brothers N——, were very politely brought back to the frontier before they had walked sixteen miles into the weird land of Eastern Bod, and Mr. K——, an ex-Lutheran minister, could not even attempt to leave his miserable village.” [Sinnett, Alfred Percy. Incidents In The Life Of Madame Blavatsky. J. W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1886): 67,68.] Blavatsky gives the name Külwein for “Mr. K——,” stating: “Met Külwein and his friend at Lahore somewhere.” [Sinnett, Alfred Percy. The Letters Of H. P. Blavatsky To A. P. Sinnett And Other Miscellaneous Letters. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. London, England. (1925): 151.] If the name Külwein is correct, than the name is likely connected to Blavatsky’s governess, Antonia Külwein. Aside from the surname, we know from Vera Petrovna (Blavatsky’s sister,) in her memoir, that Antonia’s late grandfather was a Lutheran priest and that her brother, Ernst Külwein lived in St. Petersburg in Government service. [Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. How I Was Little. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1898): 232-242.] In Isis Unveiled Blavatsky writes: “One of these was the countenance of Mr. Mr. K——‘s sister, whom he had left well and happy at home, but who, as we subsequently learned, had died some time before he had set out on the present journey.” [Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 600-601.] This could be a reference to Antonia with Blavatsky replacing her own experience for that of Mr. “K——.” Antonia died in Tbilisi in April 1850, not long after Blavatsky left her home. [Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. My Childhood. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1893): 305.]

[16] Blavatsky refers to these men as “the brothers N——.” I am using “Nemetsky,” the Russian word for “German” as a surname here. This is not the name that Blavatsky provides.

[17] Huc writes: “In 1844 they learned that their Buddha had become incarnate in Thibet; and while we were encamped Kou-Kou-Nour on the borders of the Blue Sea, we saw pass grand caravan of Khalkas going to invite this child of five old to take up his abode at L’ha-Ssa.” [Huc, Evariste Régis. Recollections Of A Journey Through Tartary, Thibet, And China. Longman, Brown, Green, And Longmans. London, England. (1852): 52.]

[18] “Sketches In Ladakh.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XXIII, No. 1,150 (January 11, 1879): 30-33.

[19] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 600.

[20] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. My Childhood. A. F. Devrien. St. Petersburg, Russia. (1893): 4-15.

[21] Blavatsky writes: “What is now generally known of Shamanism is very little; and that has been perverted, like the rest of the non-Christian religions. It is called the ‘heathenism’ of Mongolia, and wholly without reason, for it is one of the oldest religions of India. It is spirit-worship, or belief in the immortality of the souls, and that the latter are still the same men they were on earth, though their bodies have lost their objective form, and man has exchanged his physical for a spiritual nature. In its present shape, it is an offshoot of primitive theurgy, and a practical blending of the visible with the invisible world. Whenever a denizen of earth desires to enter into communication with his invisible brethren, he has to assimilate himself to their nature, i.e., he meets these beings half-way, and, furnished by them with a supply of spiritual essence, endows them, in his turn, with a portion of his physical nature, thus enabling them sometimes to appear in a semi-objective form. It is a temporary exchange of natures, called theurgy. Shamans are called sorcerers, because they are said to evoke the ‘spirits’ of the dead for purposes of necromancy. The true Shamanism—striking features of which prevailed in India in the days of Megasthenes (300 B.C.)—can no more be judged by its degenerated scions among the Shamans of Siberia, than the religion of Gautama-Buddha can be interpreted by the fetishism of some of his followers in Siam and Burmah. It is in the chief lamaseries of Mongolia and Thibet that it has taken refuge; and there Shamanism, if so we must call it, is practiced to the utmost limits of intercourse allowed between man and ‘spirit.’ The religion of the lamas has faithfully preserved the primitive science of magic and produces as great feats now as it did in the days of Kublai-Khan and his barons. The ancient mystic formula of the King Srong-ch-Tsans-Gampo, the ‘Aum mani padme houm,’ effects its wonders now as well as in the seventh century. Avalokitesvara, highest of the three Boddhisattvas, and patron saint of Thibet, projects his shadow, full in the view of the faithful, at the lamasery of Dga-G’Dan, founded by him; and the luminous form of Son-Ka-pa, under the shape of a fiery cloudlet, that separates itself from the dancing beams of the sunlight, holds converse with a great congregation of lamas, numbering thousands; the voice descending from above, like the whisper of the breeze through foliage. Anon, say the Thibetans, the beautiful appearance vanishes in the shadows of the sacred trees in the park of the lamasery.” [Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 626-628.]

[22] Britten, Emma Hardinge. Nineteenth Century Miracles. Lovell & Co. New York, New York. (1884): 348-349.

[23] “Sketches In Ladakh.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XXIII, No. 1,150 (January 11, 1879): 30-33.

[24] Vera Zhelihovskaya states that it began a year later, writing: “[The years 1853–1854 were] memorable for many reasons and to many people. A time remembered throughout Russia for the Crimean War, the death of Tsar Nikolai Pavlovich, and in many places forest fires and severe cholera; and throughout the world—the first manifestations of table-turning and spirit writing, the first rumors of Spiritualism (which had not yet been christened with this nickname.) The first rumors about an unknown force moving objects, as everyone remembers, came to us from across the ocean from the United States. Despite the hot, troubled times, and perhaps precisely because of the general unrest and anxiety, everyone eagerly pounced on the turning of tables, hats, and plates.” [Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. I” Rebus. No. 43–48 (October 28, 1884–December 2, 1884); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. II.” Rebus. No. 4–7 (January 27, 1885–February 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. III.” Rebus. No. 9–11 (March 3, 1885–March 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. IV.” Rebus. No. 13–14 (April 7, 1885–April 14, 1885.) [Preparation of the text and comments by A.D. Tyurikov. Bakhmut Roerich Society.] Another Russian Spiritualists writes: “It was only during that winter [of 1852] we heard them mentioned in society. First in the two capitals, and next everywhere, tables turned as well as hats and plates; conversations began with the help of table-tippings; and in following year planchettes came into general use. These manifestations were explained by the Spiritualistic hypothesis, that to say, questions were addressed to spirits of the departed, there was no serious inquiry into the cause of the phenomena. During the first years of the appearance of these manifestations in Russia, they did not go beyond table turning and writing, and in most cases they were used for nothing but fashionable entertainment for idle people.” [(“A Russian Spiritualist.”) “The Growth Of Spiritualism In Russia.” Light. Vol. VII, No. 326 (April 2, 1887): 148-150.]

[25] It was a conflict nominally fought over the Christian Holy Places in Jerusalem. In some sense, it was the last of the Crusades. [Mandel, Neville J. “Ottoman Policy And Restrictions On Jewish Settlement In Palestine: 1881-1908: Part I.” Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. X, No. 3 (October 1974): 312-332.] The demands of Russia stipulated that 1. All the Orthodox subjects of the Ottoman Empire would be under Russian protection. 2. That the patriarchate would be lifelong, and that no patriarchs would be dismissed. 3. A new Russian church and hospital would be built in Jerusalem, and put under the protection of the Russian consulate, and 4. A new firman would clearly point out all the rights of the Orthodox in the holy places in Palestine. [Badem, Candan. The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856.) Brill. Leiden, Netherlands. (2010): 76.]

[26] Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. I” Rebus. No. 43–48 (October 28, 1884–December 2, 1884); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. II.” Rebus. No. 4–7 (January 27, 1885–February 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. III.” Rebus. No. 9–11 (March 3, 1885–March 17, 1885); Zhelihovskaya, Vera Petrovna. “Inexplicable And Unexplained. Pt. IV.” Rebus. No. 13–14 (April 7, 1885–April 14, 1885.) [Preparation of the text and comments by A.D. Tyurikov. Bakhmut Roerich Society.]

[27] Fadeyev, Andrei Mikhailovich. Vospominaniia: 1790-1867. Vysochaishe Utverzhd. Yuzhno-Russkago. Odessa, Ukraine. [Russian Empire.] (1897): Part I: 124-125.

[28] In 1888 a copy of the Theosophical work, The Occult World, was found in the library of Ládang Monastery, the residence of the Kubgen Lama of Sikkim. Evidently the monks were delighted by Blavatsky’s message and beautified the text with their own illustrations. [Temple, Richard Carnac. Journals Kept In Hyderabad, Kashmir, Sikkim, And Nepal. W.H. Allen & Company. London, England. (1887): 176; “A Visit To Gangtok.’” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) December 18, 1889.]

[29] Huc, Evariste Régis. Recollections Of A Journey Through Tartary, Thibet, And China. Office Of The National Illustrated Library. London, England. (1852): 165.

[30] Blavatsky uses the word “Tshoutgour,” a transliteration that resembles the one used by Abbé Huc “Tchutgour,” who writes: “Medicine in Tartary, as we have already observed, is exclusively practised by the Lamas. When illness attacks anyone, his friends run to the nearest monastery for a Lama, whose first proceeding, upon visiting the patient, is to run his fingers over the pulse of both wrists simultaneously, as the fingers of a musician run over the strings of an instrument. The Chinese physicians feel both pulses also, but in succession. After due deliberation, the Lama pronounces his opinion as to the particular nature of the malady. According to the religious belief of the Tartars, all illness is owing to the visitation of a Tchutgour or demon; but the expulsion of the demon is first a matter of medicine. The Lama physician next proceeds, as Lama apothecary, to give the specific befitting the case; the Tartar pharmacopœia rejecting all mineral chemistry, the Lama remedies consist entirely of vegetables pulverised, and either infused in water or made up into pills. If the Lama doctor happens not to have any medicine with him, he is by no means disconcerted; he writes the names of the remedies upon little scraps of paper, moistens the papers with his saliva, and rolls them up into pills, which the patient tosses down with the same perfect confidence as though they were genuine medicaments. To swallow the name of a remedy, or the remedy itself, say the Tartars, comes to precisely the same thing.” [Huc, Evariste Régis. Recollections Of A Journey Through Tartary, Thibet, And China. Office Of The National Illustrated Library. London, England. (1852): 74-75.] The modern transliteration is “ada čidkür.” [Heissig, Walther. “Banishing Of Illnesses Into Effigies In Monolia.” Asian Folklore Studies. Vol. XLV, No. 1 (1986): 33-43.] Ethnologist Saijirahu Buyanchugla, Professor at Inner Mongolia University, writes: “The term ‘ada,’ which means ‘evil spirit.’ Ada čidkür (devils or demonic possession) and ada tüidker (a kind of evil spirit bringing misfortune and turbulence to human beings) use the term ‘ada’ in Mongolian, and both refer to evil spirits possessing human beings to bring them suffering. If the young female is possessed by ada, her desire of mad love will be inspired, and the patient will fall into an abnormal mental and physical state.” [Buyanchugla, Saijirahu. “Healing Practices Regenerate Local Knowledge: The Revival Of Mongolian Shamanism In China’s Inner Mongolia.” International Journal Of China Studies. Vol. XI, No. 2 (December 2020) 319-343.]

[31] Blavatsky, H.P. Isis Unveiled: Vol. II. J.W. Bouton. New York, New York. (1877): 598-602,626-628.