UPRISING

It was a time of great social change; earlier in 1831, for example, the Boston social activist, William Lloyd Garrison, began his Abolitionist journal, The Liberator.[1] “While I could not withhold from these agitators a certain measure of sympathy for their great and good object, I was utterly unable to see how their efforts tended to the achievement of their end,” Greeley would say. “Granted (most heartily) that Slavery ought to be abolished, how was that consummation to be effected by societies and meetings of men, women, and children, who owned no slaves, and had no sort of control over, or even intimacy with, those who did?”[2] The enthusiasm for Abolitionism was stunted, however, days after Greeley arrived in New York. On August 22, 1831, Nat Turner, and his lieutenants, launched the largest slave revolt in United States history. By August 24, fifty-seven whites would be killed along with two hundred blacks. After his capture, Turner would state in his confession that his apocalyptic reading of the Bible had convinced him of his divine mission. When he witnessed a solar eclipse in February 1831, he took it as an auspicious sign to execute his mission.[3]

Nat Turner. (Source: Wiki.)

PHRENOLOGY

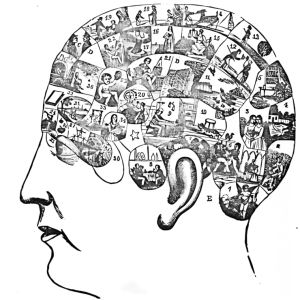

Greeley always had a way of talking profusely while at work. Conversations soon turned to Masonry, temperance, politics, and religion. The new journeyman rapidly argued his way to respectful consideration. Perfectly confident of his opinions, his talk was ardent, animated, and positive. The subject of “Cranioscopy,” or “Phrenology” as it was known in America, was much discussed at the time. Developed by the German physician, Franz Joseph Gall, the theory of Phrenology advanced four core ideas. 1. Moral and intellectual dispositions are innate. 2. The manifestation of said moral and intellectual dispositions depended on organization. 3. The exclusive organ of the mind was the brain. 4. The brain was made of as many independent organs as there were powers of the mind. It was Johann Caspar Spurzheim, Gall’s assistant, who popularized this work in America and who changed the name from Cranioscopy to Phrenology. He elaborated on the four principles of Gall, and postulated that moral and intellectual dispositions could be determined by reading the external qualities of the skull (shape, size, bumps, etc.) Spurzheim’s “doctrine of the skull” became a key feature of the American phrenologists and their followers.[4]

From: The Illustrated Self-instructor In Phrenology And Physiology.

GRAHAM

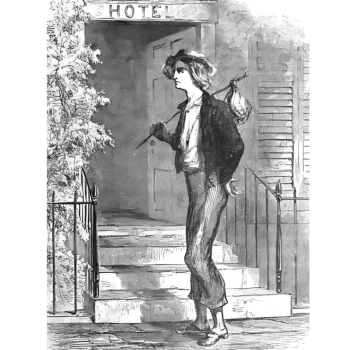

There was also the topic of Sylvester Graham who first appeared in New York as a lecturer in the Winter of 1831-1832. He was a Presbyterian clergyman, settled in New Jersey, and was styled “Dr.,” though Greeley did not know for sure if he ever studied or practiced medicine. Graham had an active, inquiring mind, and a “considerable knowledge of physics, metaphysics, and theology.” According to Greeley, “he was a fluent and forcible, though diffuse and egotistical, speaker; and he was possessed and impelled by definite convictions.” Graham was in single combat with alcohol and atheism, “but there was nothing narrow in his Temperance nor in his Orthodoxy,” according to Greeley. The “Graham System,” as taught by Graham and his followers, declared that health was the necessary result of obedience. It was the disease of disobedience and physical laws. All stimulants, “whether alcoholic or narcotic,” were pernicious, and should be rejected, save, possibly, in those rare cases “where one poison may be wisely employed to neutralize or expel another.” Naturally, Graham condemned tea, coffee, tobacco, opium, and alcoholic potables—cider and beer equally with brandy and gin. He even disapproved of all spices and condiments “save (grudgingly) a very little salt.”[5] He advocated for a vegetarian diet, and shunned the practice of city bakers who used refined flour and whitened with chemical agents. (In later years the “Graham Cracker” would be named in honor of one of his recipes.)[6] Needless to say, he opposed processed foods, especially marketplace milk (much of which came from cows fed on a diet of leftover distillery swill) that was made presentable with the addition of chalk, molasses, and plaster of Paris. He warned young men of the power of semen retention, and the dangers of losing it (from masturbation) could result in death.[7] “The power of the male organs of generation, to convert a portion of the arterial blood into semen, and to deposit that semen in its appropriate receptacles, and finally to eject it with peculiar convulsions, depends on the nerves of organic life,” Graham declared.[8]

Sylvester Graham (Source: Wiki.)

TARIFFS

Greeley, during this period, was particularly enthusiastic about the great subject of Freemasonry and the politics of Henry Clay, the Kentucky Senator and Presidential hopeful.[9] “I profoundly loved Henry Clay,” Greeley would say. “Though a slaveholder, he was a champion of Gradual Emancipation when Kentucky formed her first State Constitution in his early manhood…He was a conservative in the true sense of that much-abused term.”[10] Clay was a champion of the so-called “American System” or tariffs, a hotly contested issue of the time. It was among the many things that the North and South disagreed upon. In 1763, during the colonial period of American history, Great Britain wanted to impose new tariffs detrimental to American interests—this resulted in strenuous opposition that culminated in the American Revolution. Following the Revolution, the fledgling Government did not have the power to obtain revenue, and the united Thirteen Colonies were confronted with the problem of finance. Since tariffs afforded an indirect method of obtaining revenue, they were widely used. It was not long before the States themselves began to use tariffs as a weapon against foreign nations (as well as against one another.) The new American Constitution forbade export duties and vested in the central Government the sole authority of levying taxes on imports. The first tariff act of July 4, 1789, which lasted until 1816, was designed primarily for revenue. There was relatively little manufacturing in America at this time. Economic life was largely based on agriculture and the extractive industries. The year of the establishment of the new Federal Government in America (1789) saw the outbreak of the French Revolution which involved Europe in a quarter century of warfare. The wars that plunged Europe into destruction brought unprecedented prosperity to America, as Europe provided a ready market for American exports, and the prices of raw materials and agriculture increased dramatically. The new Government was able to finance itself without increased taxation and became quite popular. These good times came to an end when friction with England and France resulted in an Embargo Act in 1807, the Non-Intercourse Act in 1809, and ultimately war. The War of 1812 was brought about not by the trading interests of the Northeast, however, but rather by a patriotic group of frontier statesmen, the “War Hawks,” led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. They felt at the end of the conflict a sense of responsibility to the infant industry that developed during the struggle. This was the genesis of the tariff of 1816, which marked the beginning of the protective tariff system in America. Though it was labeled “protective,” in reality, it was primarily a revenue tariff; by raising the duties on cotton and wool, it gave some protection to the war industries.

The period from 1816 to 1828 marked the first important protective movement in America. The textile manufacturers in New England, the iron-workers of Pennsylvania, and the industrialists in general, wanted protection against the flood of European goods that saturated the market after the war. At the same time, owing to poor harvests in Europe, the export of agricultural products held up until the Panic of 1819. European recovery (as well as corn laws and other factors) eventually cut down agricultural exports to such an extent that new markets were sought after. Many hoped to find these new markets among the urban manufacturing populations. This is what Clay called the “American System,” a policy that developed home markets by protective tariffs and “Internal improvements” (like roads and canals) to facilitate the exchange of manufactured goods for agricultural goods in the domestic market. A tariff bill calling for a general increase in rates failed passage in 1820 by one vote. In 1824, however, the first important legislative fruit of the “American System” was passed; this bill took care of the cotton, woolen, and iron manufacturers and granted protection to producers of raw material (hemp, wool, etc.) as well. The regional divisions on the 1824 tariff were interesting, for the South, which supported the bill of 1816, now turned against protective tariffs. Then there was the highly protective Tariff of 1828 that was enacted into law during the presidency of John Quincy Adams. The South strongly opposed this tariff since it was seen as an unfair tax burden on the Southern agrarian states that imported most manufactured goods. President Jackson and his team planned a tariff that would satisfy the protective demands of the West and Middle States, but because of the high demands on raw material meant it would be obnoxious to New England. It was expected that after defeating all the amendments the bill would be met with disapproval by New England, and that region, in combination with the South, would defeat it. This was intended to throw upon Adams and New England “the obloquy of its failure” and allow Jackson and his team to pose as friends of American industry. The everyone’s surprise, New England supported the measure on the final vote, and the “Tariff of Abomination” became law. The South was thoroughly aroused in its anger, and South Carolina passed a nullification ordinance declaring the tariff law of 1828 (and the 1832 amendment) null and void. Tariff duties, a chief cause of the American Revolution, now threatened to break up the young Republic.[11] President Jackson declared that nullification was illegal and received from Congress a Force Bill that enabled him to send federal troops into any State to execute the law. Secession and Civil War seemed imminent.[12]

Lithograph depicting Jackson and Calhoun during the Nullification Crisis. (Source: Wiki)

MASONS

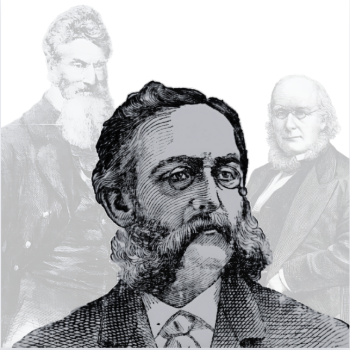

As for Masonry, that was a question much discussed at the time. In 1826 a man named William Morgan was going to publish an exposé on the Fraternity in the town of Batavia, New York. Morgan, however, mysteriously disappeared. (It was alleged that the Masons had killed Morgan and tossed his body over Niagara Falls.[13] Anti-Masonry became a political crusade that swept Western New York and New England.[14] Opponents of Masonry claimed that it was a threat to free government, and portrayed the group as a dangerous cabal intent on infiltrating the inner machinations of the Republic (with aims exerting a secret agenda.) Andrew Jackson, a high-ranking Mason, added validity to their concerns. Critics of Jackson leaped at this opportunity and created America’s earliest third party, the “Anti-Masonic Party.”[15] By 1830 there were thirty-three Anti-Masons in the New York Assembly and eight in State Senate. In popularity, it was second only to Martin Van Buren’s political machine, “The Albany Regency.”[16] This effectively weakened the vote among the Whigs for the upcoming (1832) Presidential election. “We had scarcely a chance,” said Greeley. “Anti-Masonry had divided us, and driven thousands of Adams men over to Jackson, whose personal popularity was very great, especially with the non-reading class, and who had strengthened himself at the North by his Tariff Messages and his open rupture with Calhoun.”[17] After a deadly cholera outbreak in the winter of 1831/1832, Greeley left the city to stay with relatives but returned by October to cast his vote against Jackson.[18]

William Morgan (Source: Wiki)

SOURCES:

[1] Jacobs, Donald M. “William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator And Boston’s Blacks, 1830-1865.” The New England Quarterly. Vol. XLIV, No. 2 (June 1971): 259-277; Osborn, Ronald. “William Lloyd Garrison And The United States Constitution: The Political Evolution Of An American Radical.” Journal Of Law And Religion . Vol. 24, No. 1 (2008/2009): 65-88.

[2] Greeley, Horace. The Autobiography Of Horace Greeley. E.B. Treat. New York, New York. (1872): 285.

[3] Schafer, Judith Kelleher. “The Immediate Impact Of Nat Turner’s Insurrection On New Orleans.” Louisiana History: The Journal Of The Louisiana Historical Association. Vol. XXI, No. 4 (Autumn 1980): 361-376; Santoro, Anthony. “The Prophet In His Own Words: Nat Turner’s Biblical Construction.” The Virginia Magazine Of History And Biography. Vol. CXVI, No. 2 (2008): 114-149.

[4] Mackey, Nathaniel. “Phrenological Whitman.” Conjunctions. No. 29 (Fall 1997): 231-251.

[5] Greeley, Horace. The Autobiography Of Horace Greeley. E.B. Treat. New York, New York. (1872): 103.

[6] Tompkins, Kyla Wazana. “Sylvester Graham’s Imperial Dietetics.” Gastronomica. Vol. IX, No. 1 (Winter 2009): 50-60.

[7] Burrows, Edwin G.; Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History Of New York City To 1898. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1998): 533-534.

[8] Graham, Sylvester. A Lecture To Young Men On Chastity. Light & Stearns. Boston, Massachusetts. (1837): 35.

[9] Parton, J. The Life Of Horace Greeley. Mason Brothers. New York, New York. (1856): 126.

[10] Greeley, Horace. The Autobiography Of Horace Greeley. E.B. Treat. New York, New York. (1872): 166.

[11] Taussig, F. W. “The Early Protective Movement And The Tariff Of 1828.” Political Science Quarterly. Vol. III, No. 1 (March 1888): 17-45; Faulkner, Harold U. “The Development Of The American System.” The Annals Of The American Academy Of Political And Social Science. Vol. CXLI. (January 1929): 11-17.

[12] William, Robert C. Horace Greeley: Champion Of American Freedom. New York University Press. New York, New York. (2006): 31.

[13] Brodie, Fawn M. No Man Knows My History: The Life Of Joseph Smith. Random House. New York, New York. (1971): 63.

[14] Particular attention was given to the references to the Gadianton Robbers, a secret society bound by a sacred oath to the protection of their fraternity (with the avowed goal of overthrowing the democratic Nephite Government.) The Gadianton Robbers grew so powerful that they ultimately orchestrated the events that culminate in the genocide of Moroni and the Nephite people. According to The Book of Mormon, Moroni issued this grave warning to the people of the 1830s before burying the “Golden Plates” on the Hill Cumorah. “And whatsoever nation shall uphold such secret combinations to get power and gain, until they shall be spread over the nation, behold, they shall be destroyed.” (Book Of Mormon, 2 Helaman 2:8-11.)

[15] Kutolowski, Kathleen Smith. “Freemasonry And Community In The Early Republic: The Case For Antimasonic Anxieties.” American Quarterly. Vol. XXXIV, No. 5 (Winter 1982): 543-561.

[16] Baldasty, Gerald J. “The New York State Political Press And Antimasonry.” New York History. Vol. LXIV, No. 3 (July 1983): 260-279.

[17] Greeley, Horace. The Autobiography Of Horace Greeley. E.B. Treat. New York, New York. (1872): 108.

[18] William, Robert C. Horace Greeley: Champion Of American Freedom. New York University Press. New York, New York. (2006): 26-27.