The great Roman playwright Terence said, “I am a man. Nothing human is alien to me.” It’s significant Terence was known for his comedies, since comedy is the art form that focuses most strongly on our weaknesses and our need for help from both divine and human grace and mercy.

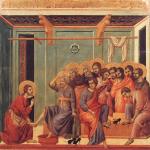

In tragedies, the protagonists die isolated in their grandeur: great men and women left in splendid ruins, while lesser beings look on in awe and say, “Now cracks a noble heart!” But in comedies, the quintessential ending is when everybody comes together at a great wedding banquet, and all’s well that ends well. It’s rather like the heaven Jesus constantly compares to a wedding banquet: the marriage supper of the Lamb in which the poor, deaf, blind and lame have the seats of honor. In comedy, we’re all in this together and — being recipients of the Playwright’s grace — we all get our richly undeserved rewards from the Founder of the Feast.

This idea that we’re all in this together — that nothing human is alien to us, and we’re all debtors to gifts and gift-givers, both divine and human, whom we can only repay by similar acts of generosity to one another — is what undergirds the last pillar of Catholic social teaching known as solidarity.

The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church tells us that solidarity: “is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say, to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all.”

As with all Catholic social teaching, solidarity has roots in Scripture — as when Paul tells the pagan Athenians, God “made from one every nation of men to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their habitation, that they should seek God, in the hope that they might feel after him and find him” (Acts 17:26-27). Solidarity emphasizes the universality of God’s provision for the human race, as well as his call to us to play an active role in that provision.

Christian faith begins, therefore, with a communal and familial understanding of the human race; because the human race springs from “one” — both the one God in whose image we are made, as well as the “one flesh” union of Adam and Eve, from whom the human race inherits its image both glorious and fallen.

The faith insists God begins with his natural creation, and his grace builds on this nature. Therefore, the Church’s social teaching applies naturally to the whole human race, not merely to Christians — since the whole human race participates in the natural law. That is why the pagan Terence knew, like the authors of Scripture, the goods of human love, family and a meal with friends — as well as the evils of murder, or a broken family, or theft.

The Fourth through the Eighth Commandments don’t tell Israel (or anybody else) something they don’t already know through the proper use of reason, but ground these universally known moral facts in God. Contempt for parents, murder, adultery and theft are bad because they harm the creatures made in God’s image. And since we are those creatures, we sooner or later have to acknowledge we must do unto others as we would have them do unto us; we must forgive as we have been forgiven; and we must be good to the alien, the orphan and the widow since we too can easily be strangers in the land of Egypt.

The Church notes that we live in a period in history when the evidence of the constitutive interconnectivity of the human race is more apparent than ever. The Compendium teaches:

“Never before has there been such a widespread awareness of the bond of interdependence between individuals and peoples, which is found at every level. The very rapid expansion in ways and means of communication ‘in real time,’ such as those offered by information technology, the extraordinary advances in computer technology, the increased volume of commerce and information exchange all bear witness to the fact that, for the first time since the beginning of human history, it is now possible — at least technically — to establish relationships between people who are separated by great distances and are unknown to each other.”

The Church hails our increasing interconnectedness as a good thing. In our intensifying global culture, it’s pretty nifty I can and do have friends not only in the U.S., but in the U.K., Australia and Nigeria. Technology has shrunk the world and brought us close to people who were in unthinkably faraway places with strange-sounding names only 20 years ago. We’re much more consciously aware than ever before of the lives, needs and hearts of people all over the globe in ever-expanding circles of friends and family. I can receive a prayer request from my Nigerian friend, post it on Facebook, and within seconds, people from Wichita to Glasgow to Sydney are part of the network of prayer that sustains his life.

But, of course, original sin extends to our global culture as well. So the Compendium continues:

“In the presence of the phenomenon of interdependence and its constant expansion, however, there persist in every part of the world stark inequalities between developed and developing countries, inequalities stoked also by various forms of exploitation, oppression and corruption that have a negative influence on the internal and international life of many states. The acceleration of interdependence between persons and peoples needs to be accompanied by equally intense efforts on the ethical-social plane, in order to avoid the dangerous consequences of perpetrating injustice on a global scale. This would have very negative repercussions even in the very countries that are presently more advantaged.”

In short, our global culture doesn’t just make it easy for me to pray for my Nigerian friend. Because of original sin, it also makes it easy for me to exploit his child and even enslave him for my morning cup of cocoa. Our God-given interdependence and our fallen and increasingly radical inequalities are in a horse race to see which rules us, and the Church calls us to work so everybody in the human family has a just share in the goods of the earth God has given us.

The way to start doing this is to start seeing the relationship between rich and poor as the Gospel does. St. John Chrysostom summarizes that relationship beautifully when he says, “The rich exist for the sake of the poor. The poor exist for the salvation of the rich.” We are emphatically all in this together, insists the Gospel. And the Christian Tradition warns it is the rich, not the poor, who are in far greater danger and in far greater need.

The Gospel repeatedly warns the rich that it is they who are in desperate need of the ministrations of the poor. This is the warning at the heart of the Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man, or in the (to our ears) strange counsel to “make friends for yourselves by means of unrighteous mammon, so that when it fails they may receive you into the eternal habitations” (Luke 16:9). The idea is precisely to turn on its head our traditional notions of patronage — wherein the poor must go hat in hand to the rich for protection, employment and sustenance — by reminding the rich that it is the prayers (or anguished cries and curses) of the poor that will spell the difference between heaven and hell for the rich. For inasmuch as we do for the least of these, we do unto Jesus himself.

The Church tells us that solidarity is both “a social principle and that of a moral virtue.” In other words, it is part of the nature of how humans are supposed to live; but — since we are fallen and often behave at odds with our own best interests — it is also a virtue we have to intentionally cultivate by denying ourselves, taking up our crosses and following Jesus.

Obvious case in point: the duty of generosity. Generosity sounds good on paper. All of us together are stronger, happier and healthier than each of us alone and relying only on our meager resources to get by in life. But, in practice, generosity means refusing my natural inclination to clutch my stuff and making the choice to risk sharing it with somebody who might cheat me or do something I disagree with or not share with me when I am in need. The biblical tradition says to this instinct, “Yes, it’s scary. Be generous anyway” — and commends, again and again, the righteous man in these terms: “One man gives freely, yet grows all the richer; another withholds what he should give, and only suffers want. A liberal man will be enriched, and one who waters will himself be watered” (Proverbs 11:24-25).

And, as the story of the Widow’s Mite (Mark 12:41-44) makes clear, the point, really, is generosity according to one’s means, not according to a dollar amount. The Widow had a couple of measly pennies to offer, but she gave generously nonetheless — as is often the case with the poor. Similarly, the question, “And who is the poor person we should care for?” is much the question, “And who is my neighbor?”: the one who has a need you can fill in the way most appropriate to his or her dignity.

Because solidarity is a social principle, the Church warns there are such things as “structures of sin.” The Compendium describes them this way:

These are rooted in personal sin and, therefore, are always connected to concrete acts of the individuals who commit them, consolidate them and make it difficult to remove them. It is thus that they grow stronger, spread and become sources of other sins, conditioning human conduct. These are obstacles and conditioning that go well beyond the actions and brief life span of the individual and interfere also in the process of the development of peoples, the delay and slow pace of which must be judged in this light. The actions and attitudes opposed to the will of God and the good of neighbor, as well as the structures arising from such behavior, appear to fall into two categories today: “on the one hand, the all-consuming desire for profit, and on the other, the thirst for power, with the intention of imposing one’s will upon others. In order to characterize better each of these attitudes, one can add the expression: ‘at any price.’”

In short, sin begins in the heart, but it does not stay there. It gets expressed in everything we do. So the things we make reflect, among other things, the sins that live in our hearts. This isn’t true merely of artists who make pornography or manufacturers who make shoddy products. It’s true of everything we make, including most especially the gigantic and globe-spanning political, social and economic systems we create to dominate the world.

A little sample of how a structure of sin works can be seen in the story found in Acts 19, when Paul went to Ephesus and challenged the cult of Artemis and the rest of pagan idolatry. Paul didn’t merely attract the hostility of her worshippers. He also garnered the wrath of the silversmiths there who manufactured shrines for her worshippers to buy. He threatened, in short, the entire economic “structure of sin” that stood behind the idol and made the Temple of Artemis (one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World) a thriving commercial as well as religious center. Result: a riot that got within an inch of killing Paul.

Now we are all at one time or another — to the degree we all sin — idolaters just like the Ephesians, since sin is the disordered attempt to get our deepest happiness from something other than God. The “Big Four” in the pantheon of idols are (and always have been): money, pleasure, power and honor. And, just as the Ephesian silversmiths did, we often create political and economic systems to support our idols.

This results in the creation of idolatrous political and economic systems that fight against those trapped within them, even those who are genuinely trying to do the right thing — just as the political and economic structures in Ephesus fought against Paul. So, for instance, we see just such a conflict in the early United States, when the Founding Fathers who fought (sincerely enough) for the proposition “all men are created equal” nonetheless were trapped in the structure of sin known as a “slave economy” and couldn’t find a way to get rid of it. Result: Thomas Jefferson — the man who wrote the Declaration of Independence and said of slavery, “Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever” — never freed his own slaves. The system of slavery enslaved Jefferson to the sin of keeping slaves.

This is why the Church insists that, in addition to confronting our personal sins, these structures of sin must be battled as well, precisely because they exert pressure on us to not repent from our personal sins. And this means, as it did with ending slavery, the involvement of the state.

This is where the Church bumps up against the libertarian and individualist piety of many Americans, who reject the idea that the state has any role to play in establishing the common good. (Indeed, for some virulent strains of libertarianism, there is a denial there’s even such a thing as the common good.)

To be sure, states have themselves often embodied precisely those structures of sin that must be reformed. But the Church has never thrown the baby out with the bathwater by arguing for the abolition of the state. Rather (and more on this next time), the Church has always affirmed the state is a good given to us by God, and, even in its corrupt form, it exists for our good (see Romans 13, written when Caesar was Nero, who would eventually kill the author of Romans 13). And this is, in no small part, because the notion that structures of sin can be confronted without any involvement of the state whatsoever is like saying a battalion of tanks can be confronted by a determined individual with a BB gun.

The words of the Compendium are clear about what is required to change structures of sin: “They must be purified and transformed into structures of solidarity through the creation or appropriate modification of laws, market regulations and juridical systems [emphasis mine].” In short, individual efforts to effect change (e.g., boycotts of corporations that support abortion or use child slaves) are wonderful, but, very often, it’s necessary to change legal, political, social and economic structures by the force of law as well. Not just the citizen, but the state, has a responsibility here.

Not that this relieves the individual of any responsibility for solidarity or the common good. On the contrary, the bulk of the responsibility falls squarely on our shoulders as disciples of Jesus Christ. Of which, more next time.