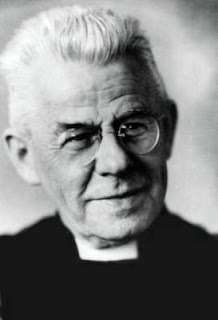

Today also marks the death of Cardinal Joseph Cardjin, and the following is taken from Catholicauthors.com:

JOSEPH CARDIJN, ELDEST SON OF HENRI CARDIJN AND LOUISE van Daelen, was born on November 13th, 1882, at Sehaerbeck, a district of Brussels, where his parents were employed as caretakers of a small block of flats. Madame Cardijn’s bad state of health did not allow her to nurse her child, and young Joseph was entrusted to the care of his grandparents, who lived at Hal, a small Flemish town to the south of Brussels, on the borders of Brabant and Hainault. His parents joined him there a few years later, and his father took up a coal merchant’s business-a very modest affair, which gave to the family a relative degree of prosperity and independence.

The childhood and adolescence of Joseph Cardijn were spent in a typical Christian home of Flanders. Monsieur Cardijn, his father, could neither read nor write, but he was a man of high principle and deep religious conviction. His children were brought up strictly, and Monsignor Cardijn has told us how one long whistle up the stairs was a sufficient reveille when he was due to serve Mass at the parish Church. He does not tell us what happened if a second call was needed!

Joseph Cardijn began his education at the elementary school with the working-class boys of the little town. The impact of industrial development was making itself felt in Flanders, and Hal was fast becoming the centre of an industrial district. When Joseph was about to leave school, his parents naturally thought of placing him in a factory, but the lad had other ambitions. This is how he has told the story of his vocation:

“It was the eve of my entry into the factory. I went up to the bedroom with my brothers and sisters. When they were all in bed, I crept down barefoot to the kitchen, where my father and mother, in spite of the late hour, were talking by the fireside.

” ‘Father,’ said I, ‘there’s something I want to ask you. Please let me continue my studies!’

” ‘But you know well enough,’ answered my father, ‘that you are the eldest, and that we rely on you to help us in bringing up your brothers and sisters.’

“But I insisted: ‘Dad, I’ve felt within me a call from God. I want to be a priest.’

“I saw two great tears roll down my father’s cheeks, and my mother became whiter than the kitchen wall. At last my father said to my mother:

” ‘Woman, we have already worked hard, but to have that joy, we will work harder still.’ “

And so Joseph Cardijn was sent to continue his studies at the College of Notre Dame de Hal. In September, 1903, he entered the Malines Seminary, and one day a message arrived that his father was dying:

“I left at once, and on entering the room where my poor father lay dying, I knelt beside him and received his blessing from his old, wrinkled hands, worn by ceaseless toil.

“Before that man who was so valiant, so great, I swore to give myself entirely, to die for the working class.”

He now saw the purpose of his vocation; he was to become a priest to give Christ to the working masses, to reveal to the workers their temporal and eternal destiny. Ever since his boyhood the problem of the working classes had haunted him.

“When fifty years ago I entered the junior seminary,” he told us recently, “my schoolmates went out to work. They were intelligent, decent, God-fearing. When I came back for my holidays they were coarse, corrupted and lapsed from the Church-whilst I was becoming a priest. I started to make enquiries, it became the obsession of my life. How did it come about that young lads brought up by Christian parents in Christian schools should be lost in a few months ?”

To the solution of this enigma he was to devote the whole of his life, but it took him many years to discover the means of fulfilling his vocation.

Joseph Cardijn was ordained priest on September 22nd, 1906, and was sent to follow a course of sociology and political science at the University of Louvain. But the following year he was recalled to his diocese and appointed to teach at the junior seminary of Basse-Wavre. He had not forgotten the problems of the working class, and he devoted his summer holidays to traveling abroad, studying working conditions in Germany, France and England. He has given us an account of his travels in England, where he visited Manchester, London and Sheffleld and made a close study of trade union organization, meeting Tom Mann and Ben Tillett. His impression of Ben Tillett is particularly interesting as it shows that, as far back as 1912, his mind was already working on the lines which were to result, some twenty years later, in the foundation of the Young Christian Workers:

“If we follow Ben Tillett during his twenty-four years of social work, it seems that two ideas have crystallized his aspirations and, like two guiding stars, have directed his efforts towards a better future: first of all, he wishes to create the most powerful, strongest, most united organization possible, in which the workers of the world will feel the solidarity of their interests and the invincible power of their union; secondly, he sets out to enable each worker in particular to educate his own individuality, to uplift himself morally and intellectually, so that he may feel the pressing need of more well-being and more justice.”

It was during one of his visits to England that he met Baden-Powell, then at the height of his fame as the founder of Scouting. Baden-Powell explained to him the Scout ideals and methods, and suggested to Father Cardijn that he should start the movement in Belgium. But though he felt an intense admiration for the educative value of Scout training, Cardijn realized that it did not hold the solution of his preoccupations: “I expounded to Baden-Powell,” he tells us, “the concrete and practical problems of the life and work of the young workers. Baden-Powell admitted that he had never looked at the problem in that way, and that Scouting could not solve this concrete and practical problem.”

In 1912, a very severe bout of illness put an end to his teaching career. Hardly convalescent, he was appointed curate at Laeken, on the outskirts of Brussels. The parish priest could hardly conceal his disappointment when he first met his new assistant: “All the parish organizations are topsy-turvy, and they send me a sick man!” It was not long before he formed a different opinion of Father Cardijn.

It was true that the parish organizations were in a bad way. The Working Men’s Club boasted of a bowls team and little else; the Girls’ Club, with a membership of thirty, offered innocent amusements to its members and a play at Christmas. No other working-class organizations existed in the parish. Father Cardijn was put in charge of the girls, and his first concern was to transform the club. Within a year he had raised the membership to 160 and had founded study-circles at which, for the first time, problems of work were discussed. This caused a mild revolution in the parish, where talk about these matters was considered dangerous and unsettling. But the young curate went still further. He founded for the young seamstresses a branch of the Needleworkers’ Trade Union, and started for the adults a section of the League of Christian Women Workers, which in a few years achieved a membership of over a thousand. He also founded a study-circle of working lads. From this group were to come the first three leaders of the Young Christian Workers-Fernand Tonnet, Paul Garcet, Jacques Meert.*

Those years were a period of ceaseless activity and experiment. Father Cardijn was not a mere theorist; he did not start off with preconceived ideas and try to force them upon reality. He was always ready to try new methods over and over again until they achieved real formative results. The War did not interrupt his efforts. In 1915, whilst remaining curate at Laeken, he was appointed Director of Social Work for the district of Brussels by Cardinal Mercier. On two occasions he was imprisoned by the Germans for patriotic activities, and during several months spent in prison-cells he was able to meditate upon his experiences and to outline what was to become the method of the Young Christian Workers. In 1919 he left Laeken and was able to devote himself full-time to social work in Brussels.

A number of Trade Union leaders had come to realize the need for grouping together young workers. The pioneers trained by Father Cardijn formed the nucleus of this new movement, which in 1919 took the name of La Jeunesse Syndicaliste (the Young Trade-Unionists). For the next few years it developed slowly, finding its way and establishing its methods, and meeting with a great deal of opposition, even, it is said, from the Cardinal Archbishop of Malines. Catholic Belgium possessed a strong network of traditional organizations, and this movement of young workers was looked upon as a dangerous and revolutionary innovation. But it managed to break through every prejudice and misunderstanding. In 1924, the Jeunesse Syndicaliste became the Jeunesse Ouvriere Chretienne, the Young Christian Workers, and Father CardIjn was appointed its National Chaplain by the Belgian bishops. In March, 1925, Pope Pius XI received in audience the founder of the Young Christian Workers, and gave to the movement the final sanction of the Church. Msgr. Cardijn has often told the story of this momentous interview. “Here at last,” said the Pope, “is someone who comes to speak to me about the masses! The greatest scandal of the nineteenth century was the loss of the workers to the Church. The Church needs the workers, and the workers need the Church.”

It is not our purpose to tell in any detail the subsequent history of the Young Christian Workers; its astonishing development in Belgium, where it became in a very short while the most powerful youth movement in the country; its growth in France, its spread in other countries, including England and the English-speaking world. One writes the history of something that is past, whereas the Young Christian Worker is a living thing, one of the most vital forces, perhaps, in contemporary Catholicism. It is at present established in more than sixty-two countries; it groups more than a million and a half young workers of every race, color and nationality. Its founder has become a world famous personality, and his name is venerated by young workers all over the world. Few men have been able to achieve so much in their lifetime. When Father Cardijn started his first small group of working lads more than thirty years ago, he said to them: “We are setting out to conquer the world.” Today the Y. C. W. International has become a reality. It has taken its place among the great world organizations, it can speak for working youth with the prestige and authority of an intetnational movement.

The writings collected in his books will, we hope, give a clear idea of the mind and spirit of the founder of the Young Christian Workers. The reader will be struck by the dynamism, enthusiasm, the freshness of vision of the man. His greatness does not lie in having discovered anything new; it consists essentially in having restated, with uncommon force and genius, truths as old as Christianity itself, truths which many of us had almost forgotten. In a period in the Church’s life which is marked by a new development of the lay apostolate, he stands out as one of the most significant figures of modern Catholicism.

* Fernand Tonnet and Paul Gareet died at Dachau Concentration Camp in February, 1945. See Marguerite Fieves: Fernand Tonnet, premier Joeiste (1947, Editions Joeistes, Brussels).

The childhood and adolescence of Joseph Cardijn were spent in a typical Christian home of Flanders. Monsieur Cardijn, his father, could neither read nor write, but he was a man of high principle and deep religious conviction. His children were brought up strictly, and Monsignor Cardijn has told us how one long whistle up the stairs was a sufficient reveille when he was due to serve Mass at the parish Church. He does not tell us what happened if a second call was needed!

Joseph Cardijn began his education at the elementary school with the working-class boys of the little town. The impact of industrial development was making itself felt in Flanders, and Hal was fast becoming the centre of an industrial district. When Joseph was about to leave school, his parents naturally thought of placing him in a factory, but the lad had other ambitions. This is how he has told the story of his vocation:

“It was the eve of my entry into the factory. I went up to the bedroom with my brothers and sisters. When they were all in bed, I crept down barefoot to the kitchen, where my father and mother, in spite of the late hour, were talking by the fireside.

” ‘Father,’ said I, ‘there’s something I want to ask you. Please let me continue my studies!’

” ‘But you know well enough,’ answered my father, ‘that you are the eldest, and that we rely on you to help us in bringing up your brothers and sisters.’

“But I insisted: ‘Dad, I’ve felt within me a call from God. I want to be a priest.’

“I saw two great tears roll down my father’s cheeks, and my mother became whiter than the kitchen wall. At last my father said to my mother:

” ‘Woman, we have already worked hard, but to have that joy, we will work harder still.’ “

And so Joseph Cardijn was sent to continue his studies at the College of Notre Dame de Hal. In September, 1903, he entered the Malines Seminary, and one day a message arrived that his father was dying:

“I left at once, and on entering the room where my poor father lay dying, I knelt beside him and received his blessing from his old, wrinkled hands, worn by ceaseless toil.

“Before that man who was so valiant, so great, I swore to give myself entirely, to die for the working class.”

He now saw the purpose of his vocation; he was to become a priest to give Christ to the working masses, to reveal to the workers their temporal and eternal destiny. Ever since his boyhood the problem of the working classes had haunted him.

“When fifty years ago I entered the junior seminary,” he told us recently, “my schoolmates went out to work. They were intelligent, decent, God-fearing. When I came back for my holidays they were coarse, corrupted and lapsed from the Church-whilst I was becoming a priest. I started to make enquiries, it became the obsession of my life. How did it come about that young lads brought up by Christian parents in Christian schools should be lost in a few months ?”

To the solution of this enigma he was to devote the whole of his life, but it took him many years to discover the means of fulfilling his vocation.

Joseph Cardijn was ordained priest on September 22nd, 1906, and was sent to follow a course of sociology and political science at the University of Louvain. But the following year he was recalled to his diocese and appointed to teach at the junior seminary of Basse-Wavre. He had not forgotten the problems of the working class, and he devoted his summer holidays to traveling abroad, studying working conditions in Germany, France and England. He has given us an account of his travels in England, where he visited Manchester, London and Sheffleld and made a close study of trade union organization, meeting Tom Mann and Ben Tillett. His impression of Ben Tillett is particularly interesting as it shows that, as far back as 1912, his mind was already working on the lines which were to result, some twenty years later, in the foundation of the Young Christian Workers:

“If we follow Ben Tillett during his twenty-four years of social work, it seems that two ideas have crystallized his aspirations and, like two guiding stars, have directed his efforts towards a better future: first of all, he wishes to create the most powerful, strongest, most united organization possible, in which the workers of the world will feel the solidarity of their interests and the invincible power of their union; secondly, he sets out to enable each worker in particular to educate his own individuality, to uplift himself morally and intellectually, so that he may feel the pressing need of more well-being and more justice.”

It was during one of his visits to England that he met Baden-Powell, then at the height of his fame as the founder of Scouting. Baden-Powell explained to him the Scout ideals and methods, and suggested to Father Cardijn that he should start the movement in Belgium. But though he felt an intense admiration for the educative value of Scout training, Cardijn realized that it did not hold the solution of his preoccupations: “I expounded to Baden-Powell,” he tells us, “the concrete and practical problems of the life and work of the young workers. Baden-Powell admitted that he had never looked at the problem in that way, and that Scouting could not solve this concrete and practical problem.”

In 1912, a very severe bout of illness put an end to his teaching career. Hardly convalescent, he was appointed curate at Laeken, on the outskirts of Brussels. The parish priest could hardly conceal his disappointment when he first met his new assistant: “All the parish organizations are topsy-turvy, and they send me a sick man!” It was not long before he formed a different opinion of Father Cardijn.

It was true that the parish organizations were in a bad way. The Working Men’s Club boasted of a bowls team and little else; the Girls’ Club, with a membership of thirty, offered innocent amusements to its members and a play at Christmas. No other working-class organizations existed in the parish. Father Cardijn was put in charge of the girls, and his first concern was to transform the club. Within a year he had raised the membership to 160 and had founded study-circles at which, for the first time, problems of work were discussed. This caused a mild revolution in the parish, where talk about these matters was considered dangerous and unsettling. But the young curate went still further. He founded for the young seamstresses a branch of the Needleworkers’ Trade Union, and started for the adults a section of the League of Christian Women Workers, which in a few years achieved a membership of over a thousand. He also founded a study-circle of working lads. From this group were to come the first three leaders of the Young Christian Workers-Fernand Tonnet, Paul Garcet, Jacques Meert.*

Those years were a period of ceaseless activity and experiment. Father Cardijn was not a mere theorist; he did not start off with preconceived ideas and try to force them upon reality. He was always ready to try new methods over and over again until they achieved real formative results. The War did not interrupt his efforts. In 1915, whilst remaining curate at Laeken, he was appointed Director of Social Work for the district of Brussels by Cardinal Mercier. On two occasions he was imprisoned by the Germans for patriotic activities, and during several months spent in prison-cells he was able to meditate upon his experiences and to outline what was to become the method of the Young Christian Workers. In 1919 he left Laeken and was able to devote himself full-time to social work in Brussels.

A number of Trade Union leaders had come to realize the need for grouping together young workers. The pioneers trained by Father Cardijn formed the nucleus of this new movement, which in 1919 took the name of La Jeunesse Syndicaliste (the Young Trade-Unionists). For the next few years it developed slowly, finding its way and establishing its methods, and meeting with a great deal of opposition, even, it is said, from the Cardinal Archbishop of Malines. Catholic Belgium possessed a strong network of traditional organizations, and this movement of young workers was looked upon as a dangerous and revolutionary innovation. But it managed to break through every prejudice and misunderstanding. In 1924, the Jeunesse Syndicaliste became the Jeunesse Ouvriere Chretienne, the Young Christian Workers, and Father CardIjn was appointed its National Chaplain by the Belgian bishops. In March, 1925, Pope Pius XI received in audience the founder of the Young Christian Workers, and gave to the movement the final sanction of the Church. Msgr. Cardijn has often told the story of this momentous interview. “Here at last,” said the Pope, “is someone who comes to speak to me about the masses! The greatest scandal of the nineteenth century was the loss of the workers to the Church. The Church needs the workers, and the workers need the Church.”

It is not our purpose to tell in any detail the subsequent history of the Young Christian Workers; its astonishing development in Belgium, where it became in a very short while the most powerful youth movement in the country; its growth in France, its spread in other countries, including England and the English-speaking world. One writes the history of something that is past, whereas the Young Christian Worker is a living thing, one of the most vital forces, perhaps, in contemporary Catholicism. It is at present established in more than sixty-two countries; it groups more than a million and a half young workers of every race, color and nationality. Its founder has become a world famous personality, and his name is venerated by young workers all over the world. Few men have been able to achieve so much in their lifetime. When Father Cardijn started his first small group of working lads more than thirty years ago, he said to them: “We are setting out to conquer the world.” Today the Y. C. W. International has become a reality. It has taken its place among the great world organizations, it can speak for working youth with the prestige and authority of an intetnational movement.

The writings collected in his books will, we hope, give a clear idea of the mind and spirit of the founder of the Young Christian Workers. The reader will be struck by the dynamism, enthusiasm, the freshness of vision of the man. His greatness does not lie in having discovered anything new; it consists essentially in having restated, with uncommon force and genius, truths as old as Christianity itself, truths which many of us had almost forgotten. In a period in the Church’s life which is marked by a new development of the lay apostolate, he stands out as one of the most significant figures of modern Catholicism.

* Fernand Tonnet and Paul Gareet died at Dachau Concentration Camp in February, 1945. See Marguerite Fieves: Fernand Tonnet, premier Joeiste (1947, Editions Joeistes, Brussels).