On the morning of September 7, 1914, eighty-five young men gathered for Mass at St. John’s Chapel on Clermont Avenue in Brooklyn. Ranging in age from eleven to seventeen, they were there for the opening of Cathedral College. The celebrant was the college rector, Bishop George Mundelein, who told them:

You are here because the priests have seen in you the signs that tell them of the fact that you are called to His service… Yours is to be a more vigorous course of training than that of other colleges, for yours is a higher work.

special measures if we would shelter those among our Catholic boys… called to the priesthood, and protect them from the modern materialistic spirit that pervades the very atmosphere.

In June 1914, the Moses estate on the corner of Washington and Atlantic Avenues was purchased for fifty thousand dollars. In July Mundelein wrote the priests of the diocese:

Rarely has a diocese undertaken a work of greater importance and of more splendid promise… Long after we have been called to receive the vineyard laborer’s wages, may it be a source of blessings to this Diocese, producing zealous, fervent and loyal priests, laboring solely for the glory of God and the salvation of countless souls.

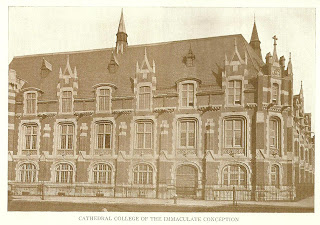

While not all of the students would be ordained, he noted, they would become committed laymen. Furthermore, he insisted, the school’s very existence embodied the diocesan commitment to fostering vocations. On 1915 the new school building was dedicated at 555 Washington Avenue.

Father Francis De Sales Healey, editor of the diocesan newspaper The Tablet, wrote that there was no “better or more blessed investment.” Addressing young Catholic men, he added:

A vocation is a precious gift, something to be watched over, nurtured and tenderly cared for. If you think God has called you to follow Him do not hesitate. If you are in doubt, pray earnestly for guidance. And when you know what God wants you to do, do it. For a vocation may be lost; hundreds have been lost.

Bishop McDonnell picked a group of capable and enthusiastic young priests for the faculty. Father Anthony Reichert from St. Barbara’s in Bushwick taught Latin, Greek and Christian Doctrine. Father Healey from The Tablet taught English. Father Francis Woods taught Math and History, and future bishop Thomas E. Molloy was spiritual director. In 1915, Bishop Mundelein was appointed Archbishop of Chicago. Nine years later he was named a Cardinal.

Father John Sharp, a future diocesan historian, was assigned to Cathedral after his ordination in 1918. He recalled the genuine excitement among the faculty about their work. Father James Higgins, who succeeded Mundelein as rector, wrote McDonnell at the start of the 1917 school year: “When one is in love with a cause or a work he is encouraged to use every lawful means to advance it. I am in love with the Cathedral College and its work.”

In 1918, Father Anthony Reichert, the college’s third rector, noted its progress. The “reverend professors,” he wrote, were “working hard,” anxious to “make Cathedral College the first in the nation.” During these early years, most of the priest faculty doubled as fulltime parish priests. Father Francis Oechsler had a long commute from St. Fidelis in College Point, but he considered this an important work, an “investment in the future.”

The first commencement exercises took place in February 1919. Twenty-five of the thirty-four graduates were later ordained priests. Over the next forty years, Brooklyn ordained an average of thirty-five men a year, the majority Cathedral alumni. To date over twelve hundred graduates have been ordained priests, over a dozen consecrated bishops, and two elevated to the College of Cardinals. In 1978 John J. Carberry, a member of the class of 1924, was the first Cathedral graduate to vote in a papal election.