An Oxford graduate and Catholic convert whose writings influenced Tolkien and T.S. Eliot, Christopher Dawson (1889-1970) has been called “the greatest English-speaking Catholic historian of the twentieth century.” In his 1950 book Religion and the Rise of Western Culure, Dawson writes that after the fall of the Roman Empire, Christianity held Western Europe together in a “spiritual community” known as Christendom, which transcended borders and politics.

For over a millennium, Roman Catholicism dominated the West’s social, political, and intellectual life, providing what Dawson calls the “dynamic element.” A large part of its influence was due to “a spirit that strives to incorporate itself in humanity and to change the world.” In short, the Church preserved the past and shaped the future. Perhaps no group contributed more significantly to this than the Benedictine monks, founded by a man whose original intent, ironically, was to shun the world.

In a recent book on St. Benedict (480-547), Father Anselm Grün aptly notes that anyone who is still being spoken of 1,500 years after his death clearly “must have been a remarkable person.” Unfortunately, very little historical material is available for painting a fuller picture of the man himself. Nevertheless, Father Grün argues, what “stands in the foreground is not the person of Benedict, but his work.”

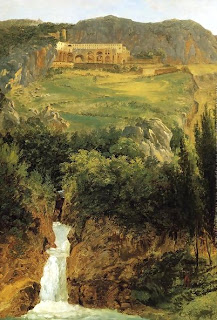

Here’s what we do know. He was born to a noble family in Italy’s Umbria region and studied in Rome. At about age twenty, disillusioned with the city’s corruption, he moved east to the mountains of Subiaco to live as a hermit. In time a community of like-minded people gathered around him, and he moved them north to Monte Cassino, where he founded a monastery. As their leader, he drew up a rule of life still used. Now known as The Rule of St. Benedict, it became the norm for monastic life in Western Europe.

The idea of a communal life devoted to spiritual contemplation didn’t start with Benedict, and it’s not an exclusively Christian tradition. In Christ’s time, the Essenes were a Jewish sect that lived a communal life. Christian monasticism first developed in Egypt under St. Antony (251-256) and expanded throughout the eastern Roman Empire. Before Benedict, St. Basil (329-379) in the East and St. Augustine (354-430) in the West created monastic rules, but neither has been as influential as St. Benedict’s.

The success of Benedictine monasticism has much to do with an emphasis on moderation, balance, and flexibility. Instead of imposing an extreme severity, Benedict calls for “nothing that is harsh and burdensome.” The order’s motto is Ora et Labora, “pray and work.” From the start, spiritual and physical activity have gone hand in hand. Because Benedict’s monastery is meant to be “a school of the Lord’s service,” there is an openness to addressing the day’s needs, including those outside monastery walls.

Under Benedict’s successors, the monasteries developed into self-supporting houses centered in rural areas. During the sixth century, people fled urban decay for the countryside in growing numbers. As the only organized communities in the area, monasteries provided leadership in a time of chaos, serving as centers of stability. Their founding intent was to be separated from the world, but the world had come to them.

In time the monasteries also became centers for spreading Christianity to the rest of Europe. In the late sixth century, a Roman monk now known as St. Augustine of Canterbury established the Church in England. Decades later, English Benedictine missionaries were sent back to the continent to evangelize the German peoples. The most famous of them was St. Boniface, “the Apostle of Germany,” who was martyred in 754.

In retrospect, it may seem strange that men pledged to live apart from the world should find themselves playing such an important role in it. But, as Blessed John Henry Newman writes,

St. Benedict found the world, physical and social, in ruins, and his mission was to restore it in the way not of science, but of nature, not as is setting about to do it, not professing to do it by any set time, or by any rare specific, or by any series of strokes, but so quietly, patiently, gradually, that often till the work was done, it was not known to be doing… Silent men were to be observed about the country, or discovered in the forest, digging, clearing, and building; and other silent men, not seen, were sitting in the cold cloister, tiring their eyes and keeping their attention on the stretch, while they painfully copied and recopied the manuscripts which they had saved. There was no one who contended or cried out, or drew attention to what was going on, but by degrees the woody swamp became a hermitage, a religious house, a farm, an abbey, a village, a seminary, a school of learning and a city.

All of this, and more, was done as Benedict would have wished, in “the Lord’s service.” And it continues today, long after the fall of Rome and far beyond the hills of Subiaco.

The above painting, titled View of the Benedictine Monastery at Subiaco, is the work of the French artist Antoine-Felix Boisselier (1790-1857).