Here’s an answer from The Brooklyn Eagle, October 18, 1890:

In each parish there is a pastor and one, two or three assistants, according to the size and needs of the congregation. Mass has to be said every morning, beginning generally about 6 o’clock, sometimes twice on Sunday, with a sermon, Sunday school and vespers, after which, during the week, the sick have to be visited, the parish generally supervised, the schools looked after, children instructed, sermons prepared and, heaviest of all loads to the pastor, the debts of the church provided against.

Born in Philadelphia, son of a Quaker father and a Catholic mother, Isaac Howell served as pastor of St. Mary’s Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey, until his death in 1866. For much of the 1800’s, Catholic priests wore suits and ties. This was a custom that was brought over from England. Formal clerical garb wasn’t mandated until the 1880’s.

On Saturday afternoons and evenings, and on the eves of the festivals and holy days confessions are heard, which means being cooped up in a box about 3 feet by 4 for five or six hours, chilled by draughts in winter, stifled by heat in summer, poisoned by fetid breaths and listening to the thousand and one woes and abominations of erring manhood. For all these the priest must have consolation, encouragement, reproof and admonition. The wicked must be directed to the paths of penitence, the just strengthened and urged to perseverance. The labors of the confessional are probably the most trying and exacting of a priest’s duties.

Born in Ireland, Father Michael King spent most of his priesthood in California, serving for forty years as pastor of Immaculate Conception Church in Oakland. The beard covering his throat was popular among Protestant and Catholic clergy during the 1800’s. In the days before central heating, it kept their throats warm while they preached in the pulpit during the winter.

Then he must be ready at any moment of the day to answer the sick calls, and no matter how virulent the pestilence or disgusting the disease, there is not a moment for hesitation before hastening to the sick bed, even though at the peril of life itself. To their eternal honor be it said that priests of this and every other land have never refused to take their lives in their hands at the call of duty, and history is full of the records of those who have fallen martyrs to the heroism with which they sought to relieve the spiritual and often the temporal wants of those committed to their charge.

Born in Ireland, Father James Hughes served in Hartford, Connecticut, for nearly fifty years. Seen here in full vestments, he died in 1895, just before receiving the news that he had been named a Monsignor.

For all this work, continued year in and year out till he falls in harness, the priest receives the good will and love of his people and superiors, the approval of his own conscience, and no matter how long or successful his term of service a maximum salary of $1,000 a year— if the parish affords it. It must be admitted that the calling is not a very alluring one to those who love ease and fat returns.

For all this he is entitled to a salary— is he is a pastor— of $1,000 a year, and to $600 if he is an assistant. He must get his salary if he can— out of the revenues of the parish to which he is attached. The parish supplies him with a house. He must find the rest himself, and if there is anything lacking the privation must be endured with the hope that the sure wages provided in the hereafter will repay for all that was wanting here below in creature comforts.

Many priests belonging to religious orders had their own unique habits. Seen here is Father John Pinasco (1837-1897), an Italian-born Jesuit who served as President of both the University of Santa Clara and the University of San Francisco.

No matter how long a priest may be pastor his salary will never increase beyond the $1,000 limit, even if he reaches the pastorship of the richest and grandest church in the diocese. There is no such thing for a Catholic priest as a call with a $10,000 echo to it. In some dioceses the maximum salary is less than $1,000, and it takes very little knowledge of the geography of Long Island to know that there are many Catholic parishes where the revenues could not afford $1,000 in salaries. The pastor must get along with what comes and trust to Providence for the rest.

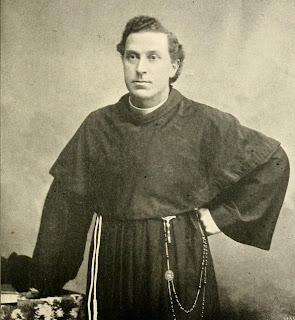

The Redemptorists were founded in 1700’s Italy, but most who came here in the 1800’s were German. Seen above in their distinctive habit is Father John Hespelin, C.Ss.R. (1821-1899), the first pastor of Holy Cross Church in Baltimore’s Federal Hill section.

The bishop’s salary is a pro rata tax fixed for each parish, to pay according to its standing. It is called he cathedraticum. As his duties are more extensive and expensive than a pastor’s the sum is therefore greater. It is one of the reasons why a good sum should be raised for Bishop Loughlin’s jubilee purse, that he has rarely asked his pastors for the cathedraticum. The venerable prelate has led so simple and unassuming a life that very little suffices for his personal needs. Hence, the diocese has not been asked for the salary, which might have amounted to several thousand dollars according to the average standard.

There is no more hardworking, industrious and self sacrificing body of men than the secular clergy, and they are the glory of the American church and one of the best elements of our American citizenship, a bulwark of morality and the highest intelligence, and an impenetrable barrier against all the subversive theories of socialistic or anarchistic violence.

A priest in the street must wear the distinctive dress of his calling. He cannot go to the theater, to horse races. He cannot sue anyone in a civil court for temporal affairs until all amicable resources are exhausted. If he brings matters of church discipline into a civil court he incurs a special excommunication which extends to all who aid or abet him. In their homes ecclesiastics wear a long coat reaching to the ground and called a cassock. For priests it is black, signifying that they are dead to the world.

The beretta is worn in everyday life and in the sanctuary at the less solemn portions of the mass, but never at the altar, in actual celebration, except in one part of the world. In China, owing to the public custom of never appearing in public uncovered, Pope Paul V (1605-1621) granted the missionaries the privilege of wearing a beretta all through mass, but it must not be the cap worn in every day life. In no other part of the world is this privilege allowed even to the pope himself. The little skull cap some priest wear is called a zucchetto, and was worn originally to protect the head made bare by the shaving in tonsure. It cannot be worn during the solemn parts of the mass.