![sulpiciansinunit00herb_0305[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/224/2012/07/sulpiciansinunit00herb_03051-249x300.jpg) On October 31st in the year 1848, Father Oliver L. Jenkins, Deacon Edward Caton, and four students arrived at an unfinished building on the Fredrick Turnpike in Maryland’s Howard County. Here, one historian notes, Father Jenkins “established himself, in the midst of poverty and hardship, as the president of St. Charles College.” According to its charter, the college was for “the education of pious young men of the Catholic persuasion for the ministry of the Gospel.” Over the next 130 years, St. Charles would educate thousands of high school and college-age young men nationwide for the Catholic priesthood.

On October 31st in the year 1848, Father Oliver L. Jenkins, Deacon Edward Caton, and four students arrived at an unfinished building on the Fredrick Turnpike in Maryland’s Howard County. Here, one historian notes, Father Jenkins “established himself, in the midst of poverty and hardship, as the president of St. Charles College.” According to its charter, the college was for “the education of pious young men of the Catholic persuasion for the ministry of the Gospel.” Over the next 130 years, St. Charles would educate thousands of high school and college-age young men nationwide for the Catholic priesthood.

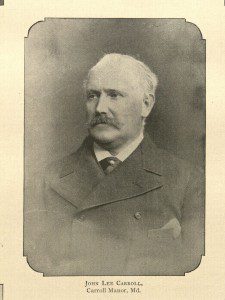

The school was named for Charles Carroll (1737-1832), the sole Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, who provided the land and the initial endowment. By the end of that first school year, St. Charleshad twelve students, mostly from Baltimore and the surrounding area. Tuition was one hundred dollars a year. The school was under the control of the Sulpician Fathers, a religious community founded in seventeenth century France to train young men for the priesthood. In 1791, having fled from revolutionary France, they founded St. Mary’s Seminary, Baltimore, America’s first Catholic theologate. In the 1840’s, they decided to establish a separate institution for high school and college-age seminarians outside of the city. In September 1848, Father Jenkins, a professor at St. Mary’s, was named president.

Jenkins was born to an affluent Catholic family in Baltimore with deep roots in Maryland. After graduating from St. Mary’s College in the city, one historian notes that “his first preference was for a business life.” For ten years he was a banker, and quite successful. After a trip to Europe, however, he began to think in other directions than finance. At twenty-eight years old, he entered St. Mary’s Seminary, and was ordained a priest in 1844. After two years as a parish priest, he joined the Sulpicians, teaching in St. Mary’s college division.

![sulpiciansinunit00herb_0317[2]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/224/2012/07/sulpiciansinunit00herb_03172-300x179.jpg) A Sulpician historian notes that his “practical turn of mind” made him an ideal candidate for St. Charles. In the early days, “he was practically the entire faculty of the college.” He was described as having “a distinguished, courtly bearing which, in conjunction with his positive character, stamped his manner with the impression of authority.” It was said that he “strictly banned all novels, and it is a tradition that no such unholy book crept into the college in his day.” Students recalled him as “so averse to giving holidays that he often hid himself in the most ridiculous places to avoid being asked.”

A Sulpician historian notes that his “practical turn of mind” made him an ideal candidate for St. Charles. In the early days, “he was practically the entire faculty of the college.” He was described as having “a distinguished, courtly bearing which, in conjunction with his positive character, stamped his manner with the impression of authority.” It was said that he “strictly banned all novels, and it is a tradition that no such unholy book crept into the college in his day.” Students recalled him as “so averse to giving holidays that he often hid himself in the most ridiculous places to avoid being asked.”

![febcatholicworld66pauluoft_0535[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/224/2012/07/febcatholicworld66pauluoft_05351-254x300.jpg) Before his death at St. Charles on July 11, 1869, the school had become a national resource for many dioceses that had no such institution of their own. Father Jenkins had given “the greater part of his fortune” to building a chapel at the college in imitation of Paris’ Sainte Chapelle, in accordance with the belief that “a chapel should be the most striking part of a Suplician college.”

Before his death at St. Charles on July 11, 1869, the school had become a national resource for many dioceses that had no such institution of their own. Father Jenkins had given “the greater part of his fortune” to building a chapel at the college in imitation of Paris’ Sainte Chapelle, in accordance with the belief that “a chapel should be the most striking part of a Suplician college.”

![febcatholicworld66pauluoft_0537[2]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/224/2012/07/febcatholicworld66pauluoft_05372-300x252.jpg) Within half a century the number of Suplician faculty had risen to seventeen and the student body to 250. Its alumni included several bishops and a cardinal. One student recalled the “hearty, simple spirit of the old days,” the corn-husking and the wood-chopping, which prepared one for “the trials and discomforts of priestly life.” One former student recalled his years at St. Charles:

Within half a century the number of Suplician faculty had risen to seventeen and the student body to 250. Its alumni included several bishops and a cardinal. One student recalled the “hearty, simple spirit of the old days,” the corn-husking and the wood-chopping, which prepared one for “the trials and discomforts of priestly life.” One former student recalled his years at St. Charles:

The religious impressions of the old times are the deepest and the strongest. Living day by day under the care of saints whose outward looks and bearing assured us beyond cavil of their spotless souls, the boys who had consecrated themselves to the highest service of God on earth preserved the earnest, reverential candor of childhood. The daily morning offering before the statue of the Blessed Virgin; the weekly prone; the midnight communion on Christmas eve, when the beautiful Gothic chapel was sweet with unaccustomed flowers, and boys went up, four by four, four by four, interminably; the elaborate decorations in honor of the Queen of May; the melodious impromptu gatherings at twilight around her statue on the lawn; the outdoor candle fête; the long, loyal devotion of sacristans to their Hidden Lord— such are the memories that stand like landmarks of a lost Eden and make us wonder whether we will ever be so thoroughly, blissfully in love with our religion again.

(St. Charles’ high school division closed in 1969, and the college in 1977.)