MR. ADAMS’ CONVERSION–

The ex-Epsicopalian Clergyman Tells How He was Led to Embrace Catholicism

(The Brooklyn Eagle, February 22, 1897, 2.)

MR. ADAMS’ CONVERSION–

The ex-Epsicopalian Clergyman Tells How He was Led to Embrace Catholicism

(The Brooklyn Eagle, February 22, 1897, 2.)

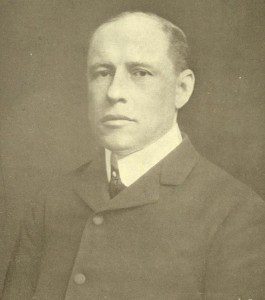

Henry Austin Adams, M.A., told the story of his conversion to the Roman Catholic Church before a large audience in the Amphion theater last evening. The lecture was accompanied with a vocal and musical entertainment under the auspices of the United Societies of Sts. Peter and Paul Church, and was for the benefit of the parochial school attached to the church. The Rev, Dr. Sylvester Malone presided.

Mr. Adams began by referring to the fact that his mother was a Catholic, and that when three weeks old he was baptized at a Catholic font. He was the seventh son, and, according to the Spanish tradition would in any case have been intended for the Church. When, later in life, he returned to the Church, after having been separated from it, most of his friends, if they spoke to him at all, carefully avoided the subject of religion; a little later they were willing to allude to the change, and still later were even eager to draw him out on the subject.

The lecturer proceeded to say: “Although I had to sacrifice the interests of friendship, relatives and ambition, I have absolutely nothing to say in antagonism of or in criticism of any of our separated brethren. My mother died when I was a mere child and my father followed my mother before my teens, dying of a broken heart. I was sent as a boy to Baltimore, one of the greatest Catholic cities in the country, where I was brought up by two devout old women and distant relations of my father. They were Methodists. Although surrounded by Catholic institutions, home influences led me to look upon the priests as sneaking, dangerous sort of men bossed from Italy.”

It was afterward agreed that he should attend the Church of the Ascension, Baltimore, “a sound Protestant church with no ritualistic nonsense.” Sometime later he had casually visited St. Luke’s Episcopalian Church.

“This was a ritualistic church,” the lecturer proceeded to say. “The altar was filled with blazing lights, and when I entered I saw the ministering priests, felt the whiff of incense and heard the voices of vested children joining in the vespers. It was a Catholic church, although not Roman Catholic.”

Mr. Adams then proceeded to describe how he had discovered a gap between the high and the low church. At the age of 17 he was admitted to the seminary in New York, where he was graduated at 22, too soon for ordination. He then went to England.

“In England,” he continued, “everything was all right. I found a thoroughly organized and devoted clergy. But the moment I crossed the channel and stepped on the continent I found I had no religion at all. But four months afterward spent in the east end of London with Father Bennett served to strengthen me, and I came back for ordination, filled with enthusiasm for the Episcopalian Church. Success attended me from the start, and my first sermon was in the diocese of Massachusetts. It was a good old time Protestant parish. The pulpit was moth eaten. I had an altar placed in the church, with candles and crucifix, said mass in vestments and began teaching them their duty exactly as Father Malone has been teaching you these many years. I was not there a year. (Laughter.) I was then sent to Trinity Church, New York, under the leadership of the eminent rector of that famous parish. It was a metropolitan pulpit, with no special parochial duties. From Sunday to Sunday I spoke to the people of Trinity Church. My reading deepened with each visit to Oxford and the continent and I began to understand more truly the philosophy of history. As I learned the truths of the Catholic Church, and as they appealed to my conscience the troubles of the wretched years which followed began. If the Episcopal Church had been telling the truth for 300 years she had not been telling it for the 1,200 years which had preceded. Bishop Potter, the suave and amiable Bishop of New York, I found was willing to let you stand in your head if you avoided scandal. I found that if one of my parishioners left my church for another in New York he was taught something entirely different from what I taught. The Rev. Heber Newton said, ‘We shall rise to better things.’ Dr. Rainsford taught a materialistic, muscular Christianity, mingled with golf and the missions of the church, and so on. Finally, I felt that I was a little pope all by myself. Then the terrible question arose in my mind, ‘Have you been misleading the people for twelve long years?’ Then I told my trouble to the Rev. William Johnston of the Church of the Redeemer, New York, and it was arranged that I should become his curate and that he should become my rector. After six months he came to me and said: ‘If you continue this longer you will go crazy. Go away.’ In two weeks I was crossing the ocean. Sitting one night, soon after, in the coffee house of a little inn in the north, reading a Scottish paper, I came across a humorous little story. It described how a parson of the new and the old church were discussing their beliefs. They went at it tooth and nail, hour after hour, arguing and hair-splitting, and introducing the arguments on either side of “the knee kirk, the woe kirk, and the kirk without the steeple,” and the “old kirk, the cold kirk, and the kirk without the people.” They could arrive at no settlement of the dispute, and and finally resolved to leave the decision to the first man who came along. He was an Irishman, and and as he consented to the referee they both argued their sides of the case before him for two hours. When the time was up the Irishman said, ‘Well, your rivirance,” turning to the old light, “you are an old man,” and, turning to the other, ‘you are a new light. I have heard of moonlight, starlight, sunlight, lamplight, gaslight and thim new electric lights, fireflies, will o’ the wisp lights, but be jabbers between the two of you there seems to be no light at all.’

A few days later, the lecturer concluded, although he had never expressed his intention to his wife, he received a cablegram from her, stating: ‘The children and I were baptized into the Catholic Church yesterday.’ Shortly afterward, the Rev. Mr. Adams concluded, he was baptized by Cardinal Newman. The lecturer was repeatedly applauded.

When he had concluded Father Malone said that the lecture should in no respect be considered a challenge. If there was one trait more than another that was admired in America it was straightforwardness and the courage to express one’s convictions, and the lecturer had possessed that admirable trait, while he had spoken without giving to the many Protestants in the audience any cause for offense.