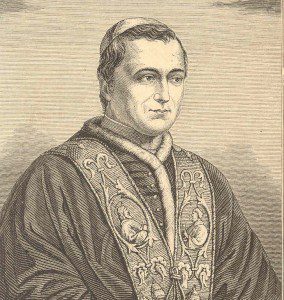

The Noble Reformer and Philanthropist Pius Ninth (The Brooklyn Eagle, November 29th, 1847)

The Noble Reformer and Philanthropist Pius Ninth (The Brooklyn Eagle, November 29th, 1847)

Although we have during the late year given a few passing notices to the character mentioned in the heading of this article—and to his moves in Italy—such a comparatively full description of the grounds on which rest his claims to public love (the dearest reward, next to a pure conscience) cannot but be in every way interesting to out readers. For our own part we look, first of all, on the arrival of each successive batch of modern news, at that which relates to Italy and the Pope. May God shield that venerable priest in personal safety, and nerve him to perseverance in his good reforms!

Cardinal Mastai Ferretti was elected Pope, June 16th, 1846, and assumed the title of Pius IX. He at once entered upon a course of the reverse of that which his predecessor had pursued. He went through the streets on foot, which the preceding popes had never done. He preached, which no pope had ever done for 300 years. He sought the society of men of talents and information, and spent much time with them, and with the officers of the government, discussing projects of reform. He gave audiences without the ordinary ceremonies, and appointed days on which the meanest subject could have free access to his person. Nor were these mean tricks to gain popularity, but the fruit of an honest desire to be acquainted with the wants of the people, that he might relieve them. A common soldier brought to him a loaf of miserable bread, and laid it on the plate of the minister of war, whom he had invited to dinner; and as the astonished functionary turned pale, charged him with the fault. After that he went through the barracks, found 4,000 loaves of a similar character, which he distributed to the poor; he degraded the minister, imprisoned his bankers, and gave each soldier money to buy bread for himself.

On the 16th of July, just one month after his elevation, to appeared the first great act of his public administration, in a decree of amnesty for political offenses, which restored to liberty, their country, their homes, and their rights of citizenship, the victims of previous tyranny, to the estimated number of 6,000. Many of them were in great poverty, and a subscription was started in Rome for their relief. Marini, governor of the city, represented to the Pope that a dangerous political motive had prompted the movement. The Pope called for the subscription paper, put down his own name for 100 and Marini’s for 10 scudi, and ordered it to be handed around amongst the nobility. Renzi, the leader of an insurrection at Riminithe previous year, called on him to return thanks for the restoration of his liberty, and was received as a son rather than a rebel, and during a long an affectionate conversation Pius took from his desk a copy of Renzi’s revolutionary proclamation, and said although many parts of it were wrong, it contained many useful suggestions of which he should avail himself. This conduct showed that he sympathized with the motives and actions of the political offenders as well as with their sufferings.

He in fact put himself at the head of the reform party, and set himself busily at work to bring about those very changes which a few months before it was treason to think of. “My people,” said he, laying his hand on the New Testament, “may expect justice and mercy from me, for my only guide is this book.” Among the subjects he addressed were the following: reform of the municipal organizations—reform of the criminal and civil code, trial by jury—suppression of vagrancy—improvement of forests and rivers—construction of railroads—the condition of the Jews in Rome—the tariff on imports—the duties upon and other articles of home production—the sanitary condition of towns and the erection of gas works. He proposed also to his council the abolition of capital punishments, and the secularizing of the state offices, which had long been monopolized by the clergy. The cardinals who composed this council were some of them shocked at the radicalism of the Holy See, and one of them told that if he did not alter the system, the people would demand a constitution, “And why,” was the answer, “should I not accede to their desire if a constitution is necessary to the welfare of my subjects.” Such an answer did not satisfy the uneasy dignitaries, and a conspiracy was formed, but its authors were discovered, the council abolished, and one appointed in its place composed of simple prelates with a single cardinal for president; and now that has also given way to a body composed partly of laymen.

Formidable opposition was experienced from neighboring despotic governments, and especially that of Austria, which made energetic protests, gathered armies, fomented insurrections, and even marched her troops into the papal territory. He has shown the sincerity of his intentions, by making, as far as possible, real concessions to liberty, and only formal concessions to despotism. Thus, in regard to the censorship of the press, a point on which the remonstrances of Austria are supposed to have been especially urgent, the subjects of the pope were greatly disappointed by the language of the decree which he issued, mitigating but slightly the severity of previous laws, and equally gratified by the new censors, who had been selected from the ranks of literary men of known liberality. The execution of the law has been so satisfactory, that the number of newspapers in Rome has trebled under its influence, and that of other publications doubled.

Throughout all these moves, the Pope has so managed both his private conduct and his public acts, as to gain the unbounded confidence of his people, and produce such good conduct, order and quiet among them as to astonish even his best friends. The Ghetto, that miserable part of Rome, in which the Jews have hitherto been confined, is thrown open, and they are allowed to live elsewhere. Some special taxes which they labored under are removed, and to insult a Jew is now a criminal offense severely punished. The law concerning the liberty of the press was so altered that the censors must hereafter be laymen.

With regard to purely ecclesiastical matters, the Pope has exhorted the religious orders to purity, the clergy to preaching with simplicity, and forbidden the ecclesiastics of Rome to attend the theater. This is an outline of the principal measures adopted by the new Pope. They give him a just claim to the sympathy and praise of all enlightened philanthropists.