![lifelifeworkofpo00mcgouoft_0493[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/224/2013/11/lifelifeworkofpo00mcgouoft_04931-201x300.jpg) There’s two ways to look at Vatican II, George Weigel suggests in his new book Evangelical Catholicism. One is to see it as a “rupture-with-the-past,” as progressive-minded Catholics are wont to do. The other, favored by the traditional-minded, is to view it as a “terribly-mistaken-concession-to modernity.” Both, he contends, are inaccurate interpretations. The real goal of Vatican II, he writes, was to reclaim the Gospel message and “propose the good news of Jesus Christ to a disenchanted world.”

There’s two ways to look at Vatican II, George Weigel suggests in his new book Evangelical Catholicism. One is to see it as a “rupture-with-the-past,” as progressive-minded Catholics are wont to do. The other, favored by the traditional-minded, is to view it as a “terribly-mistaken-concession-to modernity.” Both, he contends, are inaccurate interpretations. The real goal of Vatican II, he writes, was to reclaim the Gospel message and “propose the good news of Jesus Christ to a disenchanted world.”

An overlooked influence on the council, Weigel suggests, was Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903), who moved the Church from a defensive posture, “inviting the world into a serious conversation about the human prospect…. much of Vatican II’s teaching was made possible because of the ground broken by Leo XIII.” Ironically, Leo hasn’t had a biography for nearly a century (despite the fact that he opened the Vatican Archives to researchers in 1883).

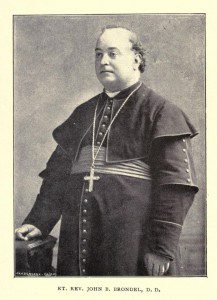

Born to a noble family on March 2, 1810, Gioacchino Pecci looked every inch the aristocrat he was. Lean, ascetical and ramrod straight, he was early noted for his brilliance and what one observer called his “exquisite tact.” He was named a Monsignor while still a seminarian, a rare exception to the rule. He earned advanced degrees in theology and law before his ordination at age twenty-seven.

After several successful years in Church government and diplomacy, Pecci was made Bishop of Perugia, and a Cardinal in 1853. Over thirty-two years, he promoted reform and strengthened outreach to the poor. At the time, Italy was undergoing the process of national unification. Although Church-state tensions ran high in an often anticlerical regime, Pecci chose dialogue over condemnation, with some success.

In 1876, Pecci was named Cardinal Camerlengo (or chamberlain) with the job of presiding over the Holy See following the pope’s death. The unwritten tradition was that the camerlengo would never become pope, but two years later, after the death of Pius IX, Pecci was elected. At sixty-eight, he wasn’t expected to stay long, but he reigned a quarter century.

Unlike Pius, who had condemned modernity in his 1864 Syllabus of Errors, the Cardinal from Perugia was known for conciliazione, a more conciliatory stance toward the modern world. The Cardinals who elected Leo wanted a more positive approach, aware that the old fortress mentality of the Counter-Reformation no longer worked (if it ever did). The world was changing rapidly, and the Church had to keep up with the pace.

In countries like France and Italy, new governments were being formed that had little regard for religion. New ideologies like Marxism, if ever fully implemented, promised to eliminate religion altogether. New schools of philosophy dispensed with God entirely, while new avenues of biblical scholarship downplayed the centrality of revelation. The Industrial Revolution created a wider gap between rich and poor.

Abroad Leo worked quietly and consistently to preserve Catholic rights. In Germany, for example, Catholicism had undergone an extended persecution called the Kulturkampf (culture war), Leo negotiated with Bismarck to end it. In a rapidly secularizing France, he encouraged Catholics not simply to call for a return to the monarchy, but to assert their rights within the existing political system to bring about desired changes.

It was by utilizing his teaching role that Leo exercised the greatest influence, writing more encyclicals than any other pope (eighty-six in total). They covered a wide range of topics: church-state relations, labor, biblical scholarship, even dueling. (The topic covered most frequently was the rosary, in eleven encyclicals.) His goal was to address every possible aspect of modern life, and to offer the Church’s perspective on a variety of issues and challenges.

An early encyclical, Aeterni Patris (1879), reaffirmed Thomas Aquinas’ Scholasticism as the cornerstone of Catholic intellectual life, a place it held for a century. At a time of rising secularism, Leo offered the modern world what he considered a positive alternative. Fourteen years later, in 1893, he issued Providentissimus Deus, encouraging Catholic biblical scholarship when secular scholars were making major inroads.

Of course, his most famous encyclical, issued in 1891, is Rerum Novarum (“Of New Things”), the cornerstone of modern Catholic social thought. As industrialization worsened the plight of workers, Leo argued that neither reckless capitalism nor its Socialist/Communist alternative were the answer. Instead, he affirmed the inherent dignity of the worker and his his right to organize collectively. While not a detailed blueprint for economic harmony, Rerum Novarum was a breakthrough in its day. In Georges Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest, the Curé de Torcy recalls:

You can read that without turning a hair, like any instruction for keeping Lent. But when it was published, sonny, it was like an earthquake. The enthusiasm!… The simple notion that a man’s work is not a commodity, subject to the law of supply and demand, that you have no right to speculate on wages, on the lives of men, as you do on grain, sugar or coffee—why it set people’s consciences upside down!

(Still, he was no man of the people. Historian Eamon Duffy notes that Leo, a thorough aristocrat, never spoke a word to his coachman in twenty-five years. That simply wasn’t done!)

Leo wasn’t always successful. After his death, Church-state relations in France reached a nadir. AeterniPatris wasn’t the last word in philosophical debates, and Rerum Novarum didn’t solve the social question. Catholic biblical scholarship received a major setback in the pontificate of St. Pius X (1903-1914), which was in many ways a throwback to the times of Pius IX. Nevertheless, George Weigel correctly notes, it’s doubtful whether Vatican II would have happened, had Leo XIII not paved the way for dialogue with the modern world, a task that Jorge Mario Bergoglio continues today as Pope Francis.