November is Black Catholic History Month, a good time to commemorate the Father of Black Catholic History: Father Cyprian Davis, O.S.B. (1930-2015). His 1990 book The History of Black Catholics in the United States inspired a generation of scholars to chronicle the subject. For Father Cyprian, history wasn’t just facts. It also had a pastoral end: to reclaim the true meaning of the word “Catholic.”

He was born Clarence John Davis in Washington, D.C., on September 9, 1930. His father was a professor at Howard University, and his mother taught public school. His relatives included the first two African American generals, Benjamin O. Davis senior and junior. This was an impressive family by any standard. In 2014, Father Cyprian reflected on his family’s heritage in America magazine:

My great grandmother was living when I was a boy and I used to visit her. Had I been a little older I could have asked her many things…. My family was ashamed about slavery, but my great grandmother would not have been ashamed about being a slave… When I think about my age, I realize now that slaves and slavery are still close by.

From childhood he read voraciously. It led him, while a high school student, to become Catholic. Reading history, he felt, “made me fall in love with one of the things history talks about, and that would be the Catholic Church.” For a Black teen in the Jim Crow era to take this step took courage. In many circles, Catholicism was considered a “white man’s church.” Furthermore, Blacks were excluded from most of Catholic life: seminaries, convents, even parishes.

Young Davis was especially interested in monasticism. After high school, he attended Catholic University, where he met a Benedictine priest from St. Meinrad Archabbey in Indiana. He soon visited the monastery and “fell in love with the place.” In 1950, he entered as the first Black novice. When he made vows, he took the name Cyprian, in honor of the third-century African bishop.

On May 3, 1956, he was ordained at St. Meinrad’s, where he would spend most of his life teaching Church history. He earned his doctorate at the University of Louvain. Known as a first rate teacher, one former student recounts:

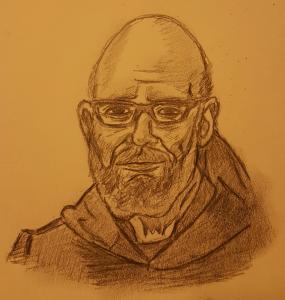

I fondly remember sitting in his classes and hanging on his every word. He was a storyteller. His voice had gravel in it, his stance was slightly bent over, and his eyes lit up as he recalled stories of the past. He also had a wonderful humor that brought those stories to life in a way that few can.

His dissertation wasn’t on African American Catholicism, but medieval monasticism. He initially wanted to avoid American history, which he found a painful subject.

During the sixties he joined the Civil Rights Movement, marching with Dr. King in Selma. As Black consciousness expanded, Father Cyprian faced what ine“a deep pastoral need.” Black Catholics wanted to know more about their own history, and they looked to a Black Catholic historian for help. Black Catholics “had a history,” Professor Cecilia Moore writes, “and they would know it.” People asked him, “Does Catholicism have anything to do with Black people?,” and “What is my place in the Church?”

Father Cyprian wrote: “That’s when I began to realize that this is important. … That’s when I began to do my own research.” In 1999, a journalist observed that he loved “finding evidence of black Catholics in places where he didn’t know they existed. For instance, he discovered, unexpectedly, that America’s first black female sculptress, Edmonia Lewis, had been a Roman Catholic.” But neither was he afraid to uncover the dark side of Catholic history, including the fact that “bishops, priests, religious men and women, and institutions such as convents, monasteries and seminaries in the United States had their slaves.”

In 1990, Crossroad published what many consider his greatest work, The History of Black Catholics. It established him as an expert on the subject. Professor Matthew Cressler describes its impact:

Black Catholic history had never truly been told before Davis’ classic. Sure, books had been written about the Church and “the Negro.” But these doubled as defenses of the Church’s relationship to African Americans. Black Catholics remained a problem rather than a people. All that changed with Davis’ History.

One reviewer called it “a chronicle both sad and inspiring.” Later an Amazon reader commented: “This is a MUST READ to learn about history most Catholics are unaware of.”

Until he passed away peacefully on May 18, 2015, Father Cyprian encouraged young scholars to explore African American Catholicism. Honored by numerous colleges and universities, he lectured worldwide, even teaching in Africa. As his former student Mark Schmidt notes, he proved that “our Catholic faith has never been nor will it ever be a ‘European’ religion.”

Father Cyprian’s book and life affected me deeply. From it I learned that Catholicism was more than just the Queens Irish neighborhood where I grew up. I saw that racism could exist both inside and outside the Church. I found new heroes in future saints like Pierre Toussaint, Henriette DeLille, and Augustus Tolton. As Father Cyprian insisted: “We’re an integral part of the church, and we’re not negligible.” And finally, what I learned there gave new meaning to the word “Catholic”: “universal.”

(*The above drawing of Father Davis is by Pat McNamara.)