Church History can often surprise you. Just when you think the Church is on her last legs, she manages to regenerate herself through the saints she produces. For example, following the disasters of the French Revolution, a revived Church produced saints like John Vianney, Therese of Lisieux, and Blessed Frederic Ozanam, to name a few. Marian apparitions like Lourdes occurred with surprising frequency. New religious orders arose regularly, and French missionaries traveled worldwide.

Church History can often surprise you. Just when you think the Church is on her last legs, she manages to regenerate herself through the saints she produces. For example, following the disasters of the French Revolution, a revived Church produced saints like John Vianney, Therese of Lisieux, and Blessed Frederic Ozanam, to name a few. Marian apparitions like Lourdes occurred with surprising frequency. New religious orders arose regularly, and French missionaries traveled worldwide.

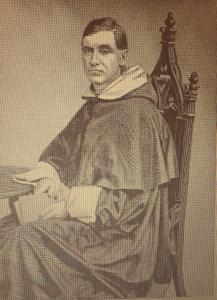

One of this revival’s major figures was Jean-Baptiste Lacordaire (1802-1861), who almost single-handedly revived the Dominican Order in post-Revolution France. A theologian and activist, Lacordaire was also considered the century’s greatest Catholic preacher, whose sermons from the Notre Dame pulpit attracted thousands. His two main themes were God and liberty.

Born in the French Republic’s final days, religion didn’t play a large role in Lacordaire’s upbringing. But the revolutionary principles of freedom, equality, and fraternity did. Originally intent on a legal career, with a talent for public speaking, he declared that the Roman Senate “would not have made me nervous.” Things looked promising, except he felt “an unsatisfied want in his heart,” which led him to re-embrace Catholicism and discern a religious vocation.

After his ordination in 1827, Lacordaire served as a diocesan priest. Contemporaries remembered him as “tall, slight, of an elegant figure, his face pale and already ascetic, but lighted up by deep eyes.” Assigned to several school chaplaincies, he found it wasn’t the classroom, but the pulpit, that attracted him.

In post-Napoleonic France, the Church allied with reactionary rulers. State control was tighter than ever. Yet Lacordaire saw Catholicism as a dynamic force capable of changing the world. With Felicite de Lammenais and Charles de Montalembert, he founded a newspaper titled L’Avenir (“The Future”); its motto was “God and Liberty.” Calling for a free Church in a free State, they looked to the the hierarchy to take the lead. But the arch-conservative Gregory XVI condemned their movement in the 1832 encyclical Mirari Vos. Lacordaire and Montalembert submitted, but Lammenais refused and was excommunicated.

In 1835, Lacordaire started preaching to large audiences at Paris’s College Stanislas, on Catholicism and citizenship. At Notre Dame in 1835 and 1836, he attracted several thousand:

What, after astonishing his hearers, conquered and captivated them, was that they did not feel in this priest either blame or contempt for the age to which they were proud to belong, and the great destiny of which was one of their dogmas. He loved it as much as they did.

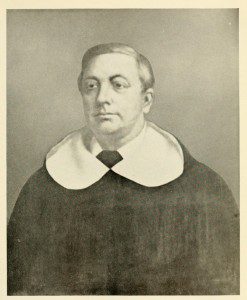

The lectures were a phenomenal success. The Archbishop of Paris called him “a new prophet.” Around this time, Lacordaire became interested in the Dominicans, officially titled the Order of Preachers, but there were none in France since the Revolution. So Lacordaire decided he would bring them back.

In 1839, he received the Dominican habit in Rome. He planned to return home: “We belong to [France]… by our baptisms, our misfortunes, and our needs, by our profound faith in her destiny, by our whole souls; we wish to die her children and her servants.” Returning in 1841, he reestablished the order’s French province and preached nationwide.

In 1843, Lacordaire was re-invited to Notre Dame. In addition to what contemporaries called a “marvelous voice,” his strengths included “clearness, force, brilliancy, the power to discuss the graver topics of the day at short notice in limited space, and in a manner adapted to the general intelligence.” Lacordaire was mainly an extemporaneous speaker. After sermons, he often fell prostrate, which he called “the torments of public speaking.”

Lacordaire seemed an ideal candidate for bishop, a friend suggested. In response, he wrote:

Do you imagine the hell there must be in the hearts of all those… who rule their lives in order to have a bishopric; who do not say a word and do not make a gesture that can place an obstacle in the way of their dream?…. Do you think, besides, that a bishopric suits my nature, and that I should be comfortable under the heap of papers and administrative notes that today constitute a bishop’s life? Pray, then, let us leave bishoprics alone… with the sincere desire that they may go to good priests.

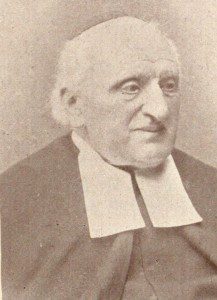

While he welcomed the Revolution of 1848, serving briefly in the National Assembly, Lacordaire unsuccessfully opposed Napoleon III’s rise. Preaching against his regime at Notre Dame in 1852, he was forced into semi-exile. His last years were tinged with sadness. A biographer notes: “He had dreamed of an alliance in France between the Church and liberty; he saw the Church seeking an alliance with power.”

To the end, Lacordaire remained committed to reconciling Church and society. In February 1860, he was elected to the Academie Francais, which one historian calls “an honor which cast a gleam of brightness over his last days.” “I wish to die,” he said shortly before his death, “a penitent religious and unrepentant liberal.” (The term “Liberal” then was used to refer to those espousing the principles of the French Revolution.)

Lacordaire matters today not just because he was a great pulpit orator in 1800’s France. But because he reminds us that the Church is not a political agency. It’s a living and life-giving force capable of bringing about positive change in society. Hence he anticipated Vatican II’s emphasis on the Church in the world, as well as the Church as the People of God. He also understood that Church and society need to be at the service of God’s People, not the rich and powerful.

(*The above drawing of Lacordaire is by Pat McNamara.)