The historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr., once called anti-Catholicism America’s most persistent prejudice. For much of the Colonial period, Catholics had no religious or civil rights. (The exception was Maryland, which was founded on the principle of religious freedom for all.) As prejudice subsided after the American Revolution, anti-Catholic laws were taken off the books. But hatred returned in the 1840’s, when immigration from Ireland and Germany increased dramatically.

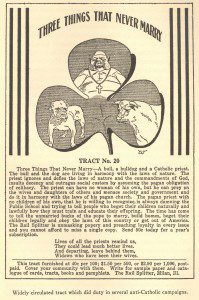

This time, anti-Catholicism took the form of the Know-Nothing Party, whose influence increased during the 1850’s, but subsided as the Civil War approached. After the war, as immigration increased from italy and Eastern Europe, the American Protective Association (A.P.A.) sought to lessen Catholic influence in public life. But by the mid-1890’s, its influence, too, waned as larger issues like war and the economy took precedence.

During the years immediately leading up to the First World War, a new wave of anti-Catholicism swept the country. Again, much of it had to do with immigration. In July 1914, Dr. Washington Gladden, a progressive-minded minister, addressed what he called the growing “anti-papal panic”: “It is evident that we are in for another fierce anti-Catholic crusade.” In response, Georgia’s notoriously anti-Catholic Watson’s Magazine commented:

Our fathers were unable to conceive of a condition of things in which a million foreigners, most of them papists, pour out of the underworld of Europe annually, and inundate our congested centres of population.

Editor Tom Watson swore: “Dr. Gladden will not see the movement against Rome die down again. Never, again!”

Undoubtedly the most visible symbol of anti-Catholicism in this era was a newspaper titled The Menace, started in 1911 in Aurora, Missouri. Within four years, it had a subscription of over 1.5 million nationwide. One historian comments on its appeal:

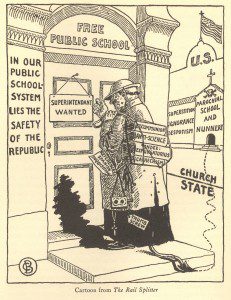

The newspaper was not opposed to Catholic religious beliefs, as such. Rather, the Menace railed against… the political machinations of Rome and the Catholic Church’s interference in American institutions and government. They campaigned against Roman Catholics running for elected office and denounced the “gigantic power of wealth, and votes, and influence” of the Catholic Church in American politics and business. They felt that a Catholic’s first loyalties lay with Rome, not the United States, and that Catholics therefore could not be trusted to uphold the Constitution of the United States.

The paper’s readership fell off with the advent of the First World War, when Germans and not Catholics became the target of popular enmity.

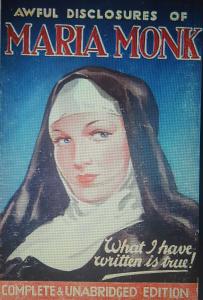

During the 1910’s, state legislatures in Alabama, Georgia, Florida and Arkansas passed what were known as “Convent Inspection Bills.” Lurid imaginations envisioned priests holding young women against their will as sex slaves, in convents that were really prisons. One Arkansas historian writes:

The Arkansas law allowed for sheriffs and constables to inspect convents, hospitals, asylums, seminaries, and rectories on a regular basis. The purpose, as stated in one section, was “to afford every person within the confines of said institutions, the fullest opportunity to divulge the truth to their detention therein.” If twelve citizens petitioned local authorities, law enforcement could enter these facilities day or night without notice.

Eventually, these laws were repealed, the last one in Georgia in 1966.

Perhaps the most ludicrous expression of anti-Catholicism occurred In Florida, where Governor Sidney Johnston Catts (1917-1921) declared that the monks of St. Leo’s Abbey were planning to arm the local African American population to aid the Germans. Pope Benedict XV, he insisted, planned to take over Florida, move there, and close all Protestant churches. (Catts did not get reelected.)

Anti-Catholicism was strong among the nation’s “old-stock” Protestant elites. The Guardians of Liberty, formed in 1911, included on its board prominent lawyers, generals, admirals, even a Methodist bishop. Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles, a national hero (and staunch anti-Catholic), addressed audiences on “America’s Danger.” One newspaper, The Christian Herald in New York, applauded the Guardians’ work:

Is free America, with its inheritance of liberty, to become Catholic America? That is the great question which now overshadows all others.

This question, however, was soon overshadowed by America’s entry into the First World War. As Catholics and Protestants fought side by side in the trenches of France, religious prejudice went on hold. But it would return with a vengeance in the 1920’s, in the revivified Ku Klux Klan and in the opposition a Catholic presidential candidate, Alfred E. Smith.

Today’s anti-Catholicism doesn’t exclude “papists” from the workplace or ballot. It doesn’t fear the pope taking over Florida, nor does it lobby against secret convent dungeons. But it does see Catholicism as the embodiment of intolerance, an enemy of the intellect and personal freedom. While much of the Church’s recent bad press is deserved, much good goes on its ministries to the poor and disadvantaged, and in many other areas. The refusal to see the good amid the bad is prejudice, and what I think it means to be anti-Catholic.

(*The drawing of General Nelson Miles is by Pat McNamara.)