Pope Francis raised more than a few eyebrows recently when he addressed the sexual exploitation of women religious by members of the clergy. It’s an issue that’s been covered up for far too long, the pontiff suggests.

Pope Francis raised more than a few eyebrows recently when he addressed the sexual exploitation of women religious by members of the clergy. It’s an issue that’s been covered up for far too long, the pontiff suggests.

Or is it?

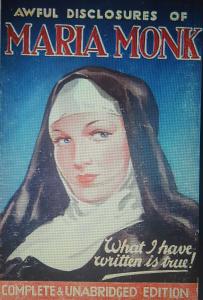

What immediately came to mind for me was that lurid nineteenth century bestseller, The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, which addressed this very topic. During the years leading up to the Civil War, it sold over 300,000 copies. (It still has readers today.) Reputedly written by an ex-nun, Charles Morris calls it “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of anti-Catholicism.”

Admittedly the book was proved to be a forgery not long after its release, but that didn’t stop people from reading it, and believing it. In the book, an idealistic young woman joins a convent, which she soon learns is connected to the priests’ residence via an underground tunnel. She also learns, according to the author, that “one of my great duties was to obey the priests in all things; and this I soon learnt, to my utter astonishment and horror, was to live in the practice of criminal intercourse with them.”

As the convent’s dark secrets are revealed, priests enter nightly to slake their lustful desires. Nuns give birth to babies who are immediately baptized, smothered, and tossed into a lime pit to eliminate the evidence. Those who protest are put on trial and sentenced to death by the bishop. They’re tied between mattresses and literally stamped to death by the rest of the nuns. Eventually the protagonist makes her escape and seeks to raise public awareness of the evils therein.

The “escaped nun” genre long predates Maria Monk, but when it came to things anti-Catholic, no other book has captured people’s attention like this one. Historian Maureen Fitzgerald writes: “the belief that convents were brothels for the use of priests, in which women were tortured and raped, was not not limited to a fringe of nativist fanatics.”

Throughout the nineteenth century, and well into the twentieth, women religious had to battle the stereotypes this book popularized. At one convent in 1850’s New Hampshire, for example, Sister Gonzaga O’Brien conducted tours on Saturday afternoons for curious locals who expected to see dungeons, torture rooms and underground tunnels. (Some visitors, in hushed voices, promised to aid her escape.)

In the years immediately preceding World War I, state legislatures in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and Arkansas passed what were known as “Convent Inspection Bills.” Lurid imaginations envisioned priests holding young women against their will as sex slaves, in convents that were really prisons. One Arkansas historian writes:

The Arkansas law allowed for sheriffs and constables to inspect convents, hospitals, asylums, seminaries, and rectories on a regular basis. The purpose, as stated in one section, was “to afford every person within the confines of said institutions, the fullest opportunity to divulge the truth to their detention therein.” If twelve citizens petitioned local authorities, law enforcement could enter these facilities day or night without notice.

Eventually, these laws were repealed, the last one in Georgia in 1966.

Every myth has some kernel of truth to it. Maybe there are no tunnels, but some clergy have indeed used their authority to sexually exploit women under their control. Admittedly, historians only now are coming to examine the issue of sexual abuse more closely than we have in the past, and we don’t know as much about it as we should. We need to know more. Knowing our past can help us as a Church address and overcome historic dysfunctions which, sadly, as the pope has pointed out, still exist today.