Pope Francis has formally cleared the way for the canonization of Blessed John Henry Newman (1801-1890), whom many consider the most important Catholic thinker since St. Thomas Aquinas. It’s been suggested that Newman could one day join Aquinas as a Doctor of the Church, for his unique contributions to Catholic intellectual life.

Pope Francis has formally cleared the way for the canonization of Blessed John Henry Newman (1801-1890), whom many consider the most important Catholic thinker since St. Thomas Aquinas. It’s been suggested that Newman could one day join Aquinas as a Doctor of the Church, for his unique contributions to Catholic intellectual life.

Many people know Newman, without actually knowing him. For example, The Pillar of the Cloud, better known by its first line, “Lead, kindly light,” was one of the most popular verses of his time, loved by Protestants and Catholics alike. Newman biographer Brian Martin writes: “It is a poem of conviction, confidence, and strong acceptance of God’s steady guidance.”

Similarly, many Catholics feel Newman’s theological influence without being fully aware of it. Newman saw that secularization would become a driving force in modern life, and that Christianity must address it in a positive, meaningful way, devoid of simple condemnation. Hence Vatican II owed Newman much, both for his understanding of the historical development of Christian doctrine, and for his assessment of the laity’s role in the world. What Newman had to say about the laity was years ahead of its time. Martin aptly comments:

He wanted Catholics to accept responsibilities in the world, exert their influence for the good, assert themselves, broaden their minds all the time knowing where truth lay; and he wanted them to be guided like fully responsible people by their educated and enlightened consciences.

Newman’s Idea of a University is still a cornerstone on higher education. In his time, too many Catholic colleges were quasi-seminaries, offering lay people a framework for pious living and little more, shielding them from modern intellectual trends. For Newman, however, the university wasn’t a seminary, but “a place to fit men of the world for the world.” Students shouldn’t be excluded from the “dangerous,” because “it is not the way to learn to swim in troubled waters never to have gone into them.”

In 1859, as Newman was having a conversation with his bishop, William Ullathorne, the topic of lay people in the Church arose. As Newman recalled, Ullathorne asked rhetorically, “Who are the laity?” Newman replied that “the Church would look foolish without them.” Today in 2019, in light of the scandals engulfing the Church, it would look doubly foolish without them.

Too often, Newman wrote, the laity “were treated like good little boys.” But when he was putting together the Catholic University of Ireland in the 1850’s, his biographer Father Ian Ker writes, he “wanted all but the theology chairs to be filled with the ablest laymen available (whatever their politics) rather than by inferior priests.” (Interestingly, Ker notes, it was the medical school that turned out to the university’s most successful institution.)

In one of his earliest works, The Arians of the Fourth Century, Newman looked at the theological controversies of that era, particularly the theological debates surrounding the nature of Christ. Was Jesus really God, or was He merely a good man? Arians argued the latter, and for a while they held power in the Church. Many bishops went Arian, while the orthodox, like St. Athanasius, were driven into exile.

Somebody had to keep the correct teaching alive, and, Newman points out, it wasn’t the bishops. It was the laity. During the fourth century, “the divine tradition committed to the infallible Church was proclaimed and maintained far more by the faithful than by the episcopate.” The majority of bishops, Newman writes, “was unfaithful to its commission, while the body of the laity was faithful to its baptism.”

In his famous essay “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine,” Newman asks the question why the Church should do so:

Because the body of the faithful is one of the witnesses to the fact of the tradition of Revealed doctrine, and because their consensus throughout Christendom is the voice of the Infallibility of the Church.

By the nineteenth century, finding orthodox bishops wasn’t a problem; it was, rather, writes Ker, “that the role of the laity would be neglected.” For Newman, “each constituent portion of the Church” had “its proper functions, and no portion can safely be neglected.” If Church leaders didn’t encourage laity to study its teaching in order to be fuller witnesses in the world, Newman predicted “indifference” among the “educated classes” and increased “superstition” among the poorer.

Don’t we find ourselves in a situation similar to Athanasius’ time? Today we admittedly face a moral scandal rather than a theological one. But we have seen many bishops unfaithful to their commission. Clearly reform has to take place. But from where? As Newman pointed out, the Church is made up of many parts, including the laity, and the Church would definitely look foolish without them.

So if reform takes place, the laity must step up to the plate and do its part. That means witnessing to the faith in the world. Priests, deacons, and religious can’t do this alone. We need an informed laity that knows the faith, and knows the world, and is ready to engage in dialogue between the two, in a mature, intelligent and positive manner. Newman saw this two hundred years ago, and that’s one of the reasons why he still speaks to us today, “heart to heart,” as his episcopal motto says.

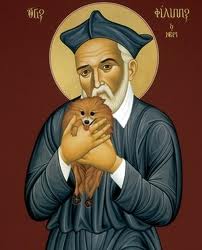

(The drawing of Blessed John Henry Newman is by Pat McNamara.)