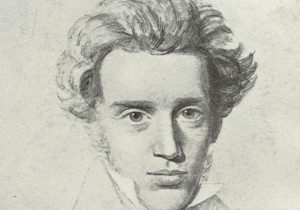

I discovered the Danish Christian existentialist philosopher Soren Kierkegaard my first year in college. He made such an impression on me that I wanted to name my first son Soren, which I would have done if my wife hadn’t objected. I left Kierkegaard behind for a long time, but over the past few weeks, I’ve been flipping through is Works of Love, where he spins off essays riffing on 15 Bible passages about love. And his piece about 1 Corinthians 8:1, “Love builds up,” is brilliant.

I discovered the Danish Christian existentialist philosopher Soren Kierkegaard my first year in college. He made such an impression on me that I wanted to name my first son Soren, which I would have done if my wife hadn’t objected. I left Kierkegaard behind for a long time, but over the past few weeks, I’ve been flipping through is Works of Love, where he spins off essays riffing on 15 Bible passages about love. And his piece about 1 Corinthians 8:1, “Love builds up,” is brilliant.

Kierkegaard points out that “building up” is a unique phrase. It isn’t just “building onto” something. It’s building from the ground up. When we apply this phrase to love, we’re obviously using it metaphorically. For love to “build up” means that love inspires and creates new reality in the heart that encounters love. The metaphor also contains the sense of encouragement. To build people up means to give them confidence and an awareness of their gifts. It is the opposite of “tearing down.”

Kierkegaard contends that if love is to build up another person, “it must mean either that the lover implants love in the heart of another person or that the lover presupposes that love is in the other person’s heart and precisely with this presupposition builds up love in him” (Works of Love, 205). So in other words, can you love people who don’t have anything to build up within them? Can you supply the thing that love builds up so that you’re building them up from scratch?

Kierkegaard says no: “It is God, the creator, who must implant love in each person, he who himself is love. Therefore it is essentially unloving and not at all up-building for anyone presumptuously to conceive of himself as desiring and able to create love in another person” (205). I cannot truly build other people up with love if I have decided that they are unlovable in themselves and it is my job to plant love in them. To conceive of love in that way is to make myself God.

Instead if I am to recognize my humble place and God’s place as the source of all love, then my love for another person cannot be my great magnanimity in loving the unlovable. One of the cruelest forms of contempt that we can show to other people is to do good deeds for them while making it clear that we find them perfectly unlovable. I once dated a woman whose ex-husband would do all kinds of good deeds around her house at least partly to show what a worthless, unskilled human being I was. Everything he did was something that I was supposed to say thank you for, but it systematically disempowered me. Love is not doing good to people you hate in order to make them feel indebted to you.

For benevolence towards others to qualify as genuine love, it must involve sympathy for the objects of your benevolence and treating them as though they are truly lovable. Here’s how Kierkegaard puts it: “Love means to presuppose love; to have love means to presuppose love in others; to be loving means to presuppose that others are loving” (211). This is radical, and it really grates against any theology that talks too stridently about the utter wickedness of human nature. Many Christians do not truly love their neighbors even though they might do good for them contemptuously because they subscribe to the doctrine of the total depravity of everyone else.

It’s true that humans are helpless without God’s grace, and that everything good we do should be understood as God’s gracious intervention in our lives. But God’s grace is operating preveniently through other people who don’t acknowledge him all the time. To “presuppose love” in other people means that I recognize that God has already been at work in their lives long before I showed up. It’s only when I presume that others have been touched by God’s love and are capable of love that I can be genuinely loving to them. All other forms of supposed benevolence and good deeds are simply ways of playing God and justifying myself.