A parable demonstrates the evolution of the Gospels and that “Inspiration” cannot mean Divine Dictation.

A parable is messy business. Although at first glance it seems straightforward and simple, looks can be deceiving. The parables of Jesus come from a very different world than the post-Industrial Western Churches of which we are so familiar.

In my previous post, I shared about the messiness of simple words found in the Gospel stories—spuriously familiar terms like “earth,” “fire,” and “salt.” These are things that at first blush appear deceptively simple and easy to grasp. When critically inspected, however, they open winding pathways into strange worlds.

The parables of Jesus are even messier to consider.

The daily Mass readings Wednesday and Thursday of this week have been on Matthean parables. Thursday’s Gospel is the Matthean version of the Parable of the Great Banquet, Matthew 22:1-14. It provides us with an excellent opportunity to see how the Gospels developed over time (see Catechism of the Catholic Church 126).

Making Distinctions

We call Thursday’s Gospel passage a parable. Except it isn’t really a parable. It is now an allegory. Perhaps some definitions are in order (courtesy of Dr. Richard Rohrbaugh):

Parables—metaphors or similes drawn from nature or common life, sometimes exaggerated to catch attention. Parables usually have one big point or punchline, the meaning of the story.

Allegories—a story that can be interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning, typically a moral or political one. In allegories, every detail can mean something else.

Allegory-Gone-Wild

Since the very beginning of the Body of Christ, followers of Jesus have been turning his parables into allegories. In fact, much of Church history has shown a predilection for allegory-gone-wild. Even the most insignificant of details Jesus said or did has been thought to be loaded with a treasury of cryptic meaning.

A simple perusal of the Church Fathers (Syriac, Greek, and Latin) shows an addiction for allegory-gone-wild. Enter Constantine, 325 CE—as life in Christ blended with all things imperial (and cruel), horrific allegories proliferated. Eventually this gave rise to pogroms and atrocities, all theologically justified in the name of Christ. More on that in a future blog.

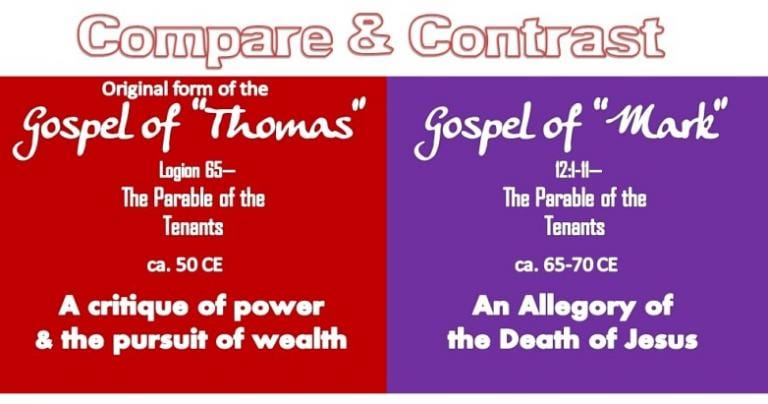

But the messiness of allegorizing Jesus-stories was already at work well before the Patristics. When scholars examine the Parable of the Tenants in Mark 12:1-12 (ca. 70 CE), they note allegorical changes had been made to an earlier version of this story. This earlier version of the story appears in the pre-Gnostic form of the Sayings Gospel of Thomas, logion 65, written twenty years prior to “Mark.”

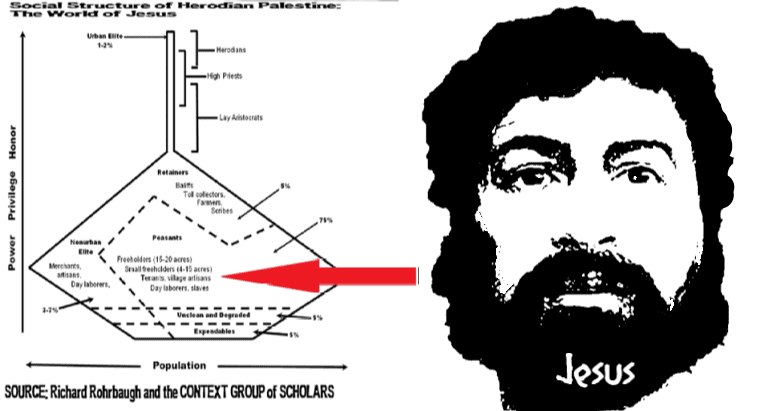

In the early version of the story (likely reflecting the original by Jesus in the 20s?), the Parable of the Tenants was a critique of avarice and power of greedy elites gained unjustly over the starving peasants. It was a story from a Galilean peasant exposing social evils happening to peasant villagers.

But “Mark” lived after Easter, decades after and somewhere far away from the Galilee. He saw Jesus as “the Beloved Son.” Therefore he transformed the Landowner, originally a wicked and godless elite, into the Father, the Patron God of Israel!

“Mark” also interpreted the tenants as those evildoers who murdered the prophets. He saw the slaves who came to them as persecuted Israelite prophets. So in “Mark” this whole story changed into an allegory of the prophets of Israel martyred for the truth. It became ultimately an allegory of the Beloved Son Jesus crucified for giving the truth. “Mark” turned Jesus’ parable into an allegory about the storyteller!

We will return to this Parable of the Tenants in a future blog post. For now, let’s look again at the Parable of the Great Banquet.

The Meaning Keeps Changing

Some form of this story likely existed well before “Matthew” got hold of it (ca. 80s CE). He went to work editing it, tweaking it, recontextualizing it. Ultimately, he converted it into an allegory about God’s judgement on the Judeans and the Temple-city Jerusalem in 70 CE. An original (and lost) form may have been spoken by Jesus who was crucified around 30 CE. Whatever the case, it wasn’t originally an allegory.

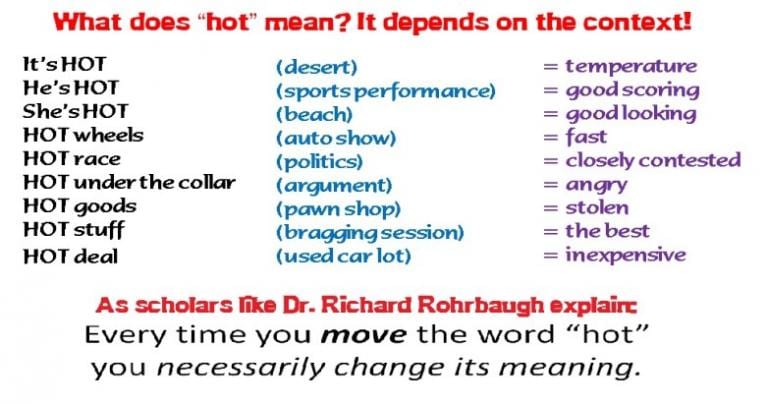

Words only mean what they mean when and where they get used. What do you think necessarily will happen to the meaning of any language when you change its location?

The Parable Moved, the Meaning Changed

Think of what happened when Jesus originally told his stories. Consider what would necessarily happen to these stories once they “hit the road.” Do that, and you will fast realize that we have a huge context problem when we explore the parables of Jesus!

Imagine the prepaschal Jesus (the historical Jesus before his death and resurrection) in the time of his earthly ministry. Picture him in Galilean villages around 29 CE, healing fellow peasants and telling parables. The stories he told there would have a certain context, that of peasant villagers and their struggles.

Now imagine a later time. Following his death, Jesus appears risen to his closest followers, and he soon becomes understood as Cosmic Lord and Messiah, soon to return to bring about Theocracy in Israel. These people talk about the Risen Lord Jesus in this way. When they remember his stories, they do so inescapably interpreting and recontextualizing them by this new context.

A Funny Comparisson

Say I was your buddy, and we spent lots of time together, and I told you some memorable jokes. You know me as your funny friend. But let’s say I die rather tragically. Then imagine God empowers you to experience me risen and reveals me to you as “Cosmic Lord.” Now when you remember that funny joke I told you, your experience of me transformed and exalted will necessarily impact how you understand my humor, right?

Before my mysterious transformation, I was your pal, the guy you laughed with, who told you funny stories. But now, illuminated by your life-changing experience, you have come to know me as the “Cosmic Lord.”All of my “jokes” are full of divine significance. It wasn’t just a regular funny guy hanging out with you who told you gags! Rather, it was the Cosmic Lord who was disclosing the will of God to you!

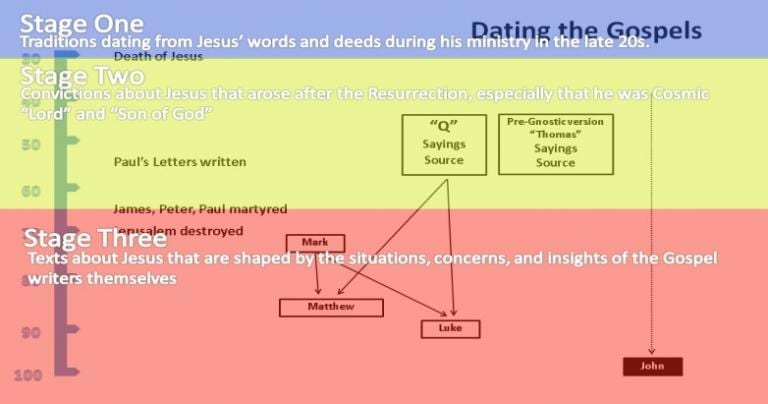

Three Stages of Gospel Development

Entering the latter half of the first century, the stories spread even further. Everyone of these new people recounted them, either from hearsay or from memory, in new and different contexts. As this expanded throughout wider geography and time, it diversified, with contexts growing exponentially. The result was Jesus’ stories changed in form and meaning.

Scripture scholars are convinced that Jesus was a master of words. He was great at insults, one-liners, zingers, and certainly parables. But they also inform us that we do not know the original historical or geographical context of any parable of Jesus. How then can we come to understand these recontextualized stories? Our closest and best link to Jesus’ original context, or the evolved contexts, is Mediterranean culture and its values.

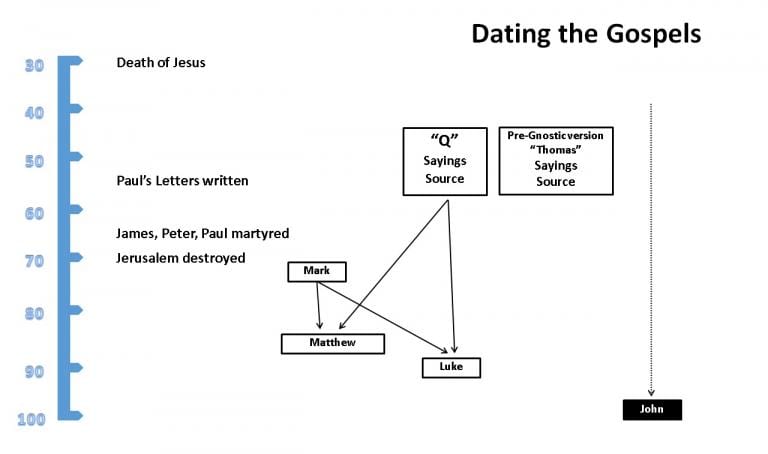

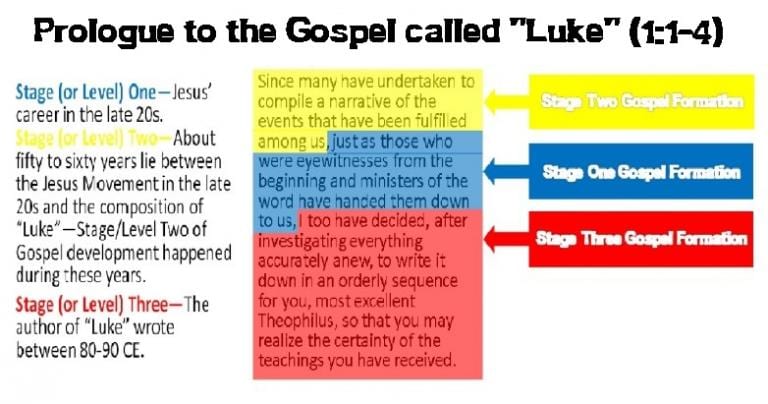

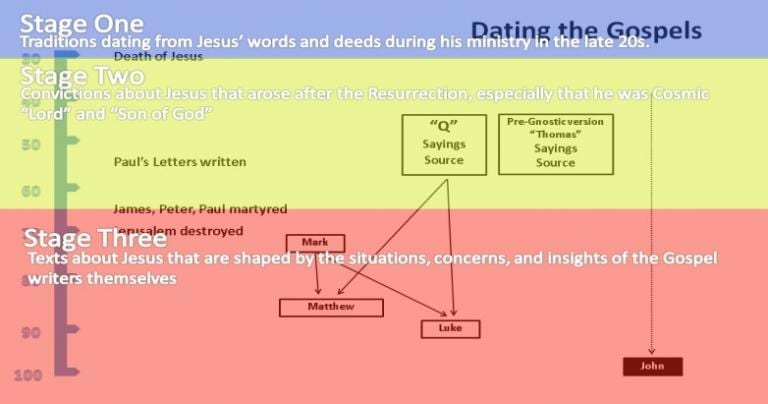

According to Vatican II’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, or Dei Verbum (§19), the Pontifical Biblical Commission’s, “Instruction on the Historical Truth of the Gospels” (§6-9), and the Universal Catechism (no. 126), the Gospels emerged through a three-stage process of development—

-

- Stage One—These are the original words and deeds of Jesus.

- Stage Two—The oral proclamation of the Apostles and disciples (including catechesis, narratives, testimonies, hymns, doxologies, and prayers).

- Stage Three—This would be the Gospel documents themselves.

Understanding the Gospels means understanding these stages. Quite often they all are on display in the same Gospel passage:

Origins of the Parable—

Returning to the Matthean “parable” of the Great Banquet, how similar is this version of the story to the one that came directly from Jesus (assuming it did)?

There are three versions of the Parable of the Great Banquet. The one in Thursday’s Gospel is a heavily edited, heavily allegorized version (Matthew 22:1-13). The other two nearly parallel one another—Luke 14:15-24 and the apocryphal Sayings-Gospel of Thomas, Logion 64.

Scholars are divided on which of these versions best represents the most primitive form of the story. They are also at odds whether all three versions stem from an earlier and lost common source. Few scholars argue against F. W. Beare’s opinion that this parable has become so “mangled” that it is impossible to recover its original form and context (See Beare, Francis Wright. The Gospel according to Matthew: A Commentary, p. 432. Oxford: Blackwell, 1981).

Let’s see some of those early recontextualizations…

Who is the Host?

In the Matthean version of this story it is a “king” who hosts the banquet. In contrast, both Thomas and “Luke” agree that it is simply a “certain man” who hosts. However, given where “Luke” situates the parable, he probably has a wealthy leader of the Pharisees in mind as host.

Disagreements among all three versions show that there have been changes. Did a king throw the banquet? Or was it a non-royal who hosted? That’s a huge difference! It changes the meaning. Who made these huge changes? We don’t exactly know.

What Was the Occasion of the Banquet?

“Matthew” says it was a “wedding feast.” Thomas tells us it is a just “a dinner.” But “Luke” says it was a “festive dinner.” The Lukan Jesus tells a story about a great dinner while he is attending a dinner himself with Pharisees. All of these details color the story differently. All give different contexts to the different versions.

It is very sobering for 21st century Christians to realize that we lack all historical or geographical context of the prepaschal Jesus’ stories. We don’t have a clue where Jesus was when he originally told this story. Likewise we aren’t sure the setting his original story had. Was it originally a wedding feast? Or was it a banquet thrown by a rich man? Or did the historical Jesus say that it was just a dinner?

We have three different authors pulling from the same Jesus story each with different contexts. Surely by the time each wrote they were all somewhere distant and removed from Jesus’ Galilean setting.

The Original Invitation/s

“Matthew” and “Luke” both agree, contrary to Thomas, that two invitations were given to the original guests. Evidence from papyrus texts exists of such ancient Mediterranean double invitations (See Kim, Chan-Hie, “Papyrus Invitation.” JBL 94 (1975), pp. 391–402).

Most scholars agree that “Matthew” never read “Luke” and “Luke” never read “Matthew.” Their versions of the story agree on the double invitations. Could it be they both used a more primitive version of the parable that had this detail?

Why does the Sayings-Gospel of Thomas, in its pre-Gnostic form written sometime in the 50s (decades before the Synoptic Gospels), lack this detail?

What are the Excuses?

Those initially invited give three excuses in both “Matthew” and “Luke.” Two of the excuses in “Matthew” appear quite similar to the first two given in “Luke.” But the third “excuse,” murdering the servants found in “Matthew” is unique to that version.

Thomas has four excuses. They all deal with merchant business. Whoever has appended the saying at the end of the Thomas version had major issues with businessmen!

The Host Reacts!

In both Synoptic versions of this story, the host becomes furious. Both “Matthew” and “Luke” express this, although the Matthean king becomes murderously so. Only the version in “Matthew” allegorizes the King’s rage into rejection of Judeans. Allegory did indeed go wild with this afterwards. The long, sad history of anti-Semitic rants through Church history has mutated this Matthean version horrifically. “Luke” shows the anger but without any allegorizing or razing cities.

Final Invitations Go Out

Servants go to the city streets to get guests in all three versions. Therefore one scholar, Bernard Brandon Scott, argues that this detail must be part of the parable’s original form (see Hear Then the Parable: A Commentary on the Parables of Jesus, p. 26. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989).

But who are these newly invited guests from the street? The highly allegorized “Matthew” says they are “bad and good alike.”

”However Thomas says different: they are anyone the servant meets.

Significantly and uniquely, “Luke” mentions two groups: first, the “poor and maimed and blind and lame” from the city streets (really should be read “the town squares”), and second, those expendables and degraded persons from the “highways and hedges” beyond the city walls.

The Place of the Feast

We never really get to the actual feast in Thomas. But both “Matthew” and “Luke” do. Both these documents explain that the banquet hall is filled. “Luke” stresses this more than “Matthew,” who merely notes it.

How Does the Story End?

All versions disagree as to the parable’s conclusion. Someone has added to the original logion in Thomas a warning for merchants and those who trouble themselves with business (perhaps as distractions to the gnosis?).

The unknown author we call “Luke” writes for an elite community in a Greco-Roman city. He is a rare elite who is deeply sensitive the plight of the poor and preserves the poverty of Jesus’ origins as well as the Lord’s concern for the poor. His version of the parable challenges his audience in this way.

As we read in yesterday’s Gospel passage, the king in “Matthew” sees a guest lacking his wedding garment. Readers should understand that such a king would provide the proper garments for nonelites coming to the banquet. This nonelite guest has refused to dress himself with the provided garment and therefore has shamed the king and host, whom he should honor.

The Matthean version (yesterday’s Gospel) was directed against Jesus’ opponents, the Jerusalem elite, so the result in “Matthew” is predictable. Servants bind hand and foot the oddly dressed guest. On orders from the king, the servants toss helpless man to the dreaded “outside.” Scholars see this an allegorizing demanded by the Matthean way of looking at history, the destruction of Jerusalem which rejected messiah Jesus.

Introductions & Conclusions

Whenever you read in the Gospels introductory and concluding statements on the parables of Jesus, rest assured that you are reading something added at a later stage. Jesus said none of these in his original stories (Stage One of Gospel Development). Almost every New Testament scholar agrees that all introductions and conclusions are later inventions.

When you read the Parable of the Great Banquet in “Matthew” the introduction given is, “Jesus again in reply spoke to them in parables…” (Matthew 22:1). Those words “again in reply” give a Matthean context to the following story, one shaped by the Matthean narrative surrounding it.

Scholars have scrutinized the document called “Matthew.” It became obvious that what the unknown author we call “Matthew” did was assemble a large collection of Jesus’ parables he had acquired from a pre-exiting written source. These probably existed in “Sayings Gospels” such as “Q” and the original form of “Thomas.”

Then, in order to plug them into his narrative skeleton, “Matthew” invents little “introductory statements” for these (e.g., “Jesus said…). Then he inserted these parables successively. This was the pattern “Matthew” followed. A dead-giveaway for this is that other Gospels showcase the same parables in ways very different from the Matthean arrangement.

“The Kingdom of Heaven may be compared to…”

Besides all this, “Matthew” also introduces Jesus’ parables in a unique manner. “Matthew” attaches the phrase, “The Kingdom of sky vault may be compared to…” as an introduction to many of the parables, including the Matthean Parable of the Great Banquet (Matthew 22:2). This curious intro is nowhere to be found in any other Gospel besides “Matthew.”

Notice that this introductory phrase is nowhere to be found in both the Lukan and Thomas versions of this parable? This phrase “The Kingdom of sky vault may be compared to…” is what scholars call a “Matthewism”—an idea particular to the Matthean community and its Gospel, not to be found in any other Gospel, and not used by the prepaschal Jesus (Stage One of Gospel Development).

Now watch what happens when you attach this phrase to the beginning of the Parable of the Great Banquet: “The Kingdom of sky vault may be compared to a king who gave a wedding feast for his son…” See what happened there? Automatically “king” becomes an analogue for God. So in the Matthean version, God hosts the banquet!

But this Matthewism was definitely not on the lips of Jesus when he told the story in its original form! So, was Jesus talking about God or about a wealthy man who throws a banquet? Jesus probably wasn’t talking about God in the original story, at least not being the host. What if he was talking about a ruthless, greedy elite?

Something Eye-Opening to Try

Try this simple exercise: examine some of Matthean parables where stuck onto “The Kingdom of sky vault may be compared to…”and then go find the same parable other Gospels. What should get clarified fast is that the character in the story (its earliest version) could not be a stand-in for the God of Israel. Removing the Matthean introduction results in dropping the idea that this host is an analogue for God.

Matthew’s Favorite Punchlines

In the Parable of the Great Banquet, different writers attached radically different concluding statements, This is another tell-tale sign that reveals to scholars that none of these originated on the mouth of Jesus. These statements “sum up” in the minds of the later authors the point and meaning of the parable (to them!).

Reading “Luke,” his conclusion to this parable is the host declaring, “I tell you none of those invited will taste my dinner.” The Matthean version is radically different—“For many are called, but few are chosen.”

The author we call “Matthew” seems to be in love with this closer, “For many are called, but few are chosen.” He uses it several times, attaching it to the end of different parables. While other Synoptic Gospels also employ this concluding statement, interestingly, they never do with this story. According to Richard Rohrbaugh, “Matthew” used it repeatedly like an all-purpose punchline.

All the evidence demonstrates that the unknown writers of the Gospels (Stage Three) invented the intros and concluding punchlines. Critical study of the Gospels shows these were unknown to the prepaschal Jesus (Stage One). Only the psychological condition called fundamentalism seems impervious to this evidence. If we drop his punchline, the meaning of the story changes.

Why All the Recontextualizing?

Again when these stories moved their meaning necessarily changed. Western interlinears, dictionaries of Greek and Hebrew and Aramaic, and concordances, cannot be of any help without also knowing the Mediterranean cultural world from which the Gospels and their parables come. Reading the Bible is an experience of cross-cultural communication, and Mediterranean culture is the first interpretation of Scripture.

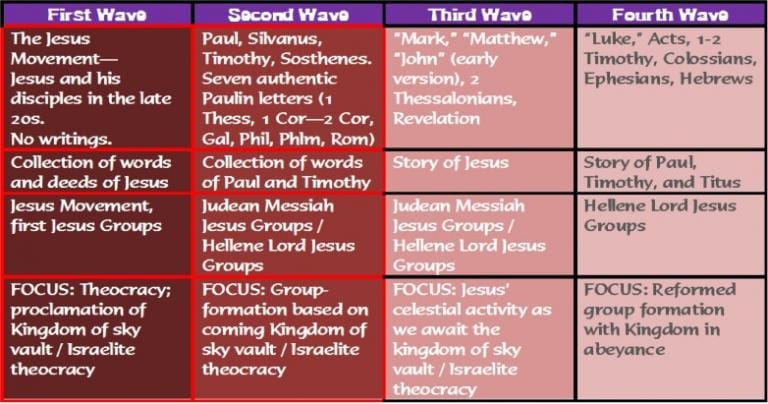

But meaning was lost and gained a long time before post-Industrial Western Bible readers arrived. Galilean peasants were illiterate. Stage One of the Gospel Tradition and the First Wave of the Jesus Movement was illiterate. Only two percent of Jesus’ society were able to read and write.

Once we reach the literate stage of the Jesus Tradition, we have crossed the immense social chasm from Galilean peasantry into those with elite social status. Interpreting Jesus, the perspective of Mediterranean elites would differ from his earlier peasant contemporaries.

And different kinds of crises abounded at different times throughout the three stages of Gospel development. The social reality of those Galilean day laborers in the Jesus Movement was not the same as in the Jesus groups of Mediterranean Israelite emigres formed by Paul. And the circumstances and crises of the Markan Jesus group were not those of Paul’s twenty years earlier.

Uncrossable Social Barriers, Crossed

Early Jesus Groups did not understand Jesus’ parables adequately. Outside of Jesus’ starving peasant context, the inspired and anonymous Evangelists—elites all—were often unfamiliar with peasant life in the Galilee of decades earlier. Despite the names tradition tags these writers with, none of them had known the earthly Jesus. But they labored to pass on the words of the Master and find relevance and meaning within them.

These authors were far-removed from the world of Jesus. They lived far later than the First Wave of the Jesus Movement. Clueless as to the original meaning of the stories, distant from their original context, they assigned every detail they could find symbolic value for something else. Consequently, they turned parables into allegories.

Some Takeaways and Hope

Catholic Christians believe that the canonical Gospels (not Thomas in any form) are inspired. But if our faith truly is consonant with reason, we cannot mean by “inspiration” that “God dictated the sacred texts.”

It is true that we do not hold early texts like “Thomas” and hypothetical “Q” and “M” and “L” to be inspired. But we cannot pretend to be blind to the fossils of these lost writings seen buried in the Gospels we do reverence and acknowledge. We Catholics living today cannot afford to be like the fabled Aristotelian priests who refused to peer through Galileo’s telescope.

We hold that the Gospels are true. But that does not mean we believe their every detail to be factual, 21st century historiographical truth. It also does not mean we must believe that every story and word attributed to Jesus in the Gospels is something the Jesus of history actually said.

From the very beginning we see the messy struggle to keep the Master’s words going. This should give us hope. Wary of the fundamentalistic idol of the false god certitude, we, like our ancestors in the Faith, must grapple.

Inspiration is a messy business. So is hope.