Meaning lost!—The parable misnamed “The Prodigal Son” is neither about Forgiveness nor Repentance.

This week we will be exploring the messy arrangement of this past Sunday’s Gospel, Luke 15:1-32. We are given, in a certain context, three parables about lost things. Today we focus on the longest and last of the three parables.

Spurious Familiarity is Bad for Bible Reading

Traditionally, this story, called wrongly “The Parable of the Prodigal Son,” has been understood to be a tale about repentance. Is it? If so, why does it never mention the term “repentance”?

Further, does the younger son actually ever repent? He does not seem motivated to return to his household because of divine grace and family generosity, but rather primarily due to his stomach. His plan was to return to his family by way of work.

Since this story is not really about a prodigal son at all, why should we call it “the Parable of the Prodigal Son?” Following verse 24, the so-called “prodigal” vanishes. There’s a whole lot of story left!

Lost Understanding: It’s About Family

This kinship story is really concerned with tragic problems experienced by a foolish yet giving Mediterranean father and his two terrible sons. Better names for the story include—“the Parable of the Two Lost Sons,” or, “The Parable of How Greed Destroys a Family,” or even, “A Dysfunctional Mediterranean Family and its Neighbors.”

Following culturally informed scholars like Richard Rohrbaugh and John Pilch, we have to ditch our Western reading glasses and put on our culturally-sensitive Mediterranean lenses when reading the Bible. Or similar to what Yoda tells Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back, we must unlearn what we have learned. We have learned to be spuriously familiar with these stories. So that is why much Western preunderstanding of this parable must be unlearned.

If we dare unlearn in this regard, we may just recognize what so many theologians and exegetes overlook: this story, its storyteller, and its original audience were thoroughly Mediterranean. Before doing soteriological dances with it, or basking in our own sentimental feels occasioned by spuriously familiar readings, shouldn’t we ask what was the reaction of original listeners when they heard it told?

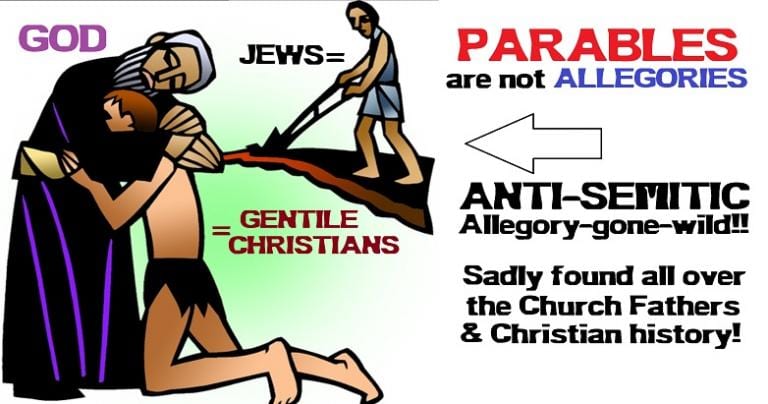

Allegory-gone-wild and Antisemitic Reading

One thing we should avoid doing is something, sadly, much of Christian history has been guilty of, namely, turning this parable into an allegory. We have spoken about allegory-gone-wild before in this blog.

Deplorably, the typical allegorical form of this parable shown repeatedly throughout Church history has been antisemitic. It imagines the father standing in for God, the older son representing the Jews (or Jewish Christians), and the younger son being analogue to Gentile Christians. Let’s trash this subtle and repugnant antisemitism.

Sorry to some Catholic fundamentalists and popular authors who clamor for returning to Patristic readings, but we need some restraint here. The wild allegory found in Ambrose, Augustine, Cyril of Alexandria, Bede, et al., has zero connection on the stage of the prepaschal Jesus or even that of the author we call “Luke.” Unlike the old hymn “Old Time Religion,” even if such allegorizing served our Fathers, that does not necessarily mean that it will be “good enough for me!”

More Wild Allegory: This is Us and God

Another, milder form of this is to spiritualize the two sons into being US! So you will hear in a multitude of homilies and sermons that WE present-day church-goers are both sons, in good and bad, in sin and repentance, and in self-righteousness and unforgiveness. Could that have been the intention of Jesus or “Luke”?

No matter how the sons have been and continue to be allegorized, almost all interpreters pigeonhole the Father as being a stand-in for God. Hopefully through this post we will see that such a popular analogy cannot be what Jesus or “Luke” intended.

A Foolish Failure of a Middle Eastern Father

Reading the beginning of this parable (Luke 15:11-24), it’s good to point out that only a foolish Mediterranean, Middle Eastern father would distribute inheritance while still breathing (see Sirach 33:20-24; b. Baba Metzia, 75b). But even if he foolishly did, he could still expect to live off the proceeds for the rest of his days. And yet don’t miss the point, though—by doing this, such a fool disgracefully destroys his authority and the honor of his family! More on this soon.

The picture of the foolish father provided by the Lukan Jesus is of a substantial peasant landowner. We can say that safely because the parable details his owned slaves (15:22).

The Lost Younger Son

Despite the disagreement of the otherwise brilliant Amy Levine who anachronistically mistakes this story for a (post-500 CE) Jewish one (it cannot be), the younger son does wish his father dead. Shamefully, while father yet breathes, he demands his inheritance as well as the power of disposing it.

In effect, the younger son has cut apart his group-self with father, his brother, and the entire village. Recall that in an earlier post we spoke about healing and what it means.

This parable also is one of many Biblical tales of terror. Remember that Biblical documents and stories are high context—much is left unsaid. The authors expect their audiences to fill in the culturally-appropriate auxiliary background information.

Lost Cause for Failed Fatherly Discipline

What should a Middle Eastern father, insulted by such a shameful outrage, do? Everyone from that world knows the prescription. He should have physically disciplined this son right there, brutally and publicly, even to death. But he does not, and this demonstrates to the whole village two things: First, that the father is stuck like glue onto the disgraceful son in a crazy attachment. Second, that he is a fool and utter failure as a Mediterranean father.

In ridiculous disgrace, the idiotic father acquiesces to his son’s demand. In the collectivistic world of the Bible, there is no privacy. Everyone’s business there is getting into everyone ELSE’S business! The gossip-network spreads like fire. Like lightening, everyone in the village would know this family’s horrific shame.

Question: can you see what terribly desperate peril this Mediterranean family faces?

The Other Lost Son, a Complete Disgrace

Consider the elder son. Why doesn’t he do what is culturally-appropriate? Specifically, why does he not protest the disgraceful property division, refuse his share, defend his father’s honor, and broker peace between his brother and father? Perhaps it is because the elder son is no better than the younger? Instead of protesting the inappropriate property division and refusing his share, he accepts it (v. 12). Why? It must be because he, also, is a disgrace.

The village would stretch its ears to hear the cries of protest and refusal coming from the elder son. But nothing is heard. Therefore, every villager would recognize the older son also as a shameless, greedy, and disloyal wretch.

A Family Lost to the Village

The result of this infamy would be this family would necessarily become utterly alienated from the village. This family bears a terrifying sickness. The contagion could spread out, destroying the whole village! The foolish father and his two greedy sons behave improperly, out of alignment with social expectations. Nonconformity threatens the stability of village life in the Middle East.

The situation is dire. Americans and other 21st century Western individualists must grapple to understand that so much more is at stake than internal family happiness at Thanksgiving dinners and Christmas get-togethers. All villagers would be alerted to expeditiously wall-off this sick family and stop its insanity lest everything in their world disintegrate.

The Lost Honor of the Younger Son

The peasant village would mark well the depths of depraved shame belonging to the younger son. People who travel in this world (e.g., Jesus, both as village artisan and folk healer) were considered as social deviants. Peasants were attached to ancestral lands and family. That this young son leaves shocks the village as it would shock whatever form of this story the historical Jesus told and as it would also shock the audience of “Luke.”

Think of Biblical sons as the social security for their mothers. The disgraceful younger son abandons her too, and by selling his part of the family wealth, he further alienates and enrages his village neighbors (see 1 Kings 21:3).

What Lost Land Means

Context Scholars like Richard Rohrbaugh explained that this younger son who “gathered all he had” did the unthinkable by selling his part of the land. Doing that, he thereby violated inalienability, a peasant norm. This ancestral land, used for subsistence farming in support of many extended family members, is forever lost. Forget about North American “nuclear families” when you are reading Scriptures! This man’s actions devastatingly impact many others.

Arranged endogamous marriage—ideally to his patrilateral first cousin—was expected of this young son to be honored, along the village pattern of networked nuclear families. This would help maintain the greater ingroup, all the needed networks in this collectivistic society, and ensure that the land remained with the ingroup. (By the way, when Christians speak about “Biblical marriage,” this is what they should imagine.)

But in a bizarre display of horrific disgrace, the younger son abandons custom, marriage, and village. Given the patrilocality of arranged marriage unions in the Middle Eastern world of Jesus and the greater Mediterranean world of “Luke,” the village must be his greater extended kinship network. He has left it unforgettably betrayed and wounded.

Village Customs Not Working

Despite what the older brother later claims (Luke 15:30), the Greek text does not tell us exactly how the younger son spent his money. It merely says he spent it wastefully (ζῶν ἀσώτως). Worse still, he wastefully blows it in a distant (read non-Israelite) land. The land of his fathers, shamefully liquidated, is wasted to the benefit of non-Judeans.

Scholars like Rohrbaugh explain that the social sciences have recorded many examples of this common pattern when dislocated, third-world peasants enter cities. Acquainted with living hand to mouth in their native village and lacking experience handling capital for the long haul, they continue in this trusted pattern once in the city. Out of place and ill-equipped with a tradition unworkable apart from its village setting, tragically, they are destroyed.

A Lost Son “Joins Himself” to a Foreign Patron

The young man starves as famine ravages the land. Desperately, he seeks aid from a wealthy urbanite patron (Luke 15:15). Since he is able to hire day laborers, this landowner is probably an elite.

It is not surprising that the young son is well accustomed to Mediterranean patronage. Patronage of some sort is to be found at all levels of peasant societies. Generally, peasants seek the aid of patrons, whether they be urbanites, hacienda-owners, or religious leaders. Understanding this helps illuminate the real meaning behind the Aramaic “abba” and why the Lord’s Prayer is thoroughly a Galilean peasant prayer.

So typical of sophisticated city-dwellers with largesse and how they relate to poor country-folk since the days of Cain and Abel, this urbanite humiliates the young son by offering him repulsive work. This is the way of urbanites toward peasants from time immemorial—repel, ridicule, ignore, exploit, and humiliate. But astonishingly, the Judean peasant agrees to feed swine.

Repentance or Stomach?

John Pilch explains that the carob pods fed to the pigs, tantalizing to the starving son, are a wild, bitter variety. These are really inedible by humans. The situation is completely nauseating and desperate. Although as a hireling he would be entitled to a share of butchered pigs, this is a verboten barrier too far, and so the young man sits at rock bottom.

Then comes these verses:

Luke 15:17-19—

But when he CAME TO HIMSELF he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have bread enough and to spare, but I perish here with hunger! ‘I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against sky vault and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.”’

Reading this story as a tale of repentance, forgiveness, and salvation (i.e., a soteriological story), the vast majority of readers have understood these verses as the “turning point” in the story. This then is the critical moment when the sinner repents! So we arrive at the classic understanding of the story, the outcome of which was immortalized by Rembrandt:

But a critical reading willing to challenge our spurious familiarity and feels shows this is not really the case. As scholars like Bernard Brandon Scott have shown, this young man is driven by his stomach and is not repentant in the true sense.

Biblical “Self” Means “Group-Self”

As Rohrbaugh has shown, the key phrase is “came to himself.” Rather than meaning he had second thoughts, the expression probably signifies the starving son remembers his own village past, and thus, he remembers who he is. In other words, he remembered his GROUP-SELF. This is a moment of self-recognition.

Keep in mind that this young man is not an individualistic American. “Self” means different things according to different cultures. The younger son is a collectivistic, dyadic personality. The characters of this story, just like Jesus and his peasant audience and the author we call “Luke,” are all personality types quite alien to us introspective individualists.

The younger son, just like all biblical characters, is anti-introspective. Such personalities internalize and make their own what others say, think and do about them. Living out the expectations of others is ardently held by such people to be an essential for human life. It is the kinship network or village, and not the isolated individual, that is their psychological center. Anything from Freud or Jung or their followers simply does not apply to them.

In peasant societies “self” means group-self. Identity means family identity. The younger son “coming to himself” or self-recognition, therefore, means recognizing his lost group-identity. He recognized his family from where he derived his identity and from which he had separated himself.

The Dangerous Road Ahead

But how can he care for his father in old age, or support his family? He forever lost the land. He has forever diminished the prospects of his kin and village.

But if he became a “hired servant” of his family, he could repay what he squandered. This means that he could take care of his father until his death. This would be a kind of recovery of honor. And he would be with family again.

But he knows the dangers of returning. Upon reaching the edge of the village, the males will line up, meeting him with a gauntlet of derision and violence. They will shame him, disown him, reject him, abuse him. Remember: he violated them all, took his inheritance before his father died, and lost it to non-Israelite (Sirach 26:5). But for life, food, and proximity to his group-self, he figures it worth the cost.

Inside the Foolish Failure of a Father

Homilists and preachers tend to be committed to the wrong idea that the foolish father in the story is an analogue for God (whom they also mistake to be a Western Daddy). They imagine him pacing back and forth, day after day, at the window looking out, watching for his lost son to return. This is why, they think, he sees the wretched son coming home “from a distance” (Luke 15:20).

Why the father sees the son coming from a distance, at the edge of the village not due to some daily routine of emotional vigilance. Rather it is caused by the spontaneously formed Middle Eastern crowd surrounding the boy, with taunts of derision, and shouts of violence.

Consistently for the story, the foolish father yet again acts totally at odds with cultural character. Imagine him bundling up his robes and hobbling down way, panting. In the Mediterranean world, old men do not run. Running is shameful (ankles show, legs show). This signifies to everyone a cultural failure for a father completely out of control over his house.

Why the Failed Father Ran

Emergency, however, might motivate an old Mediterranean man to run. The unique Greek term employed here, δραμων, means “to exert oneself to the limit of one’s powers.” This explains why the father runs. It is not because he is being a post-Industrial sentimental Daddy and misses his boy, but because his younger son faces terrible danger. He is not running to welcome him, Western readers! He runs to save the boy’s life from Middle Eastern, agonistic, violent village retribution!

He publicly forgives the son by kissing him again and again on the cheeks, and heals the broken relationship between them. His kissing his son and his embracing him is not primarily to welcome him back, but rather mainly to PROTECT HIS LIFE. He runs to save the boy and also to save his family.

Understanding this Strange Scene

To understand this scene we must step away from popular Western misconceptions of it. Does the father have tremendous love for his son? Surely he does. He has a crazy attachment for the boy. By the standards of a Mediterranean audience, he should beat this worthless young man publicly for his shameful acts. However keep in mind that the villagers here not only disapprove of the son, but also of this failed father!

Why do the villagers fear and deplore the son? It is because his abhorrent behavior could be replicated in their own sons. Why do the villagers fear and deplore the father? He gave in! This scene then is more than just fatherly love being given to a lost son. The whole family of the failed father needs to be saved. Reconciliation here goes way beyond just getting the younger son home!

Everything done by the father serves as a communication to the village. The robe publicly given to the son (Luke 15:22) could only be the father’s very own—it shouts “Accept him being part of the family.” The robe, signet ring, and sandals publicly demonstrates the boy’s reintegration into the family. He is son. Mere slaves do not bear the deepest trust and honor signified by that ring! Slaves do not wear the sandals of a free man. When the slaves place the sandals on his feet, they are signaling their own acceptance of this disgrace no more as disgrace, but as son.

More is Still Required

Will this be enough to win the village’s recognition? No. Something more is needed, and the father knows it. Keep in mind that the father and older son have also offended the community. These offences must be blotted out by something greater than this display at the edge of the village. No confidence or solidarity will be reestablished otherwise.

The village has been offended and alienated from the family. So the father kills a calf (Luke 15:23), a rare and expensive gesture. More than one hundred people could feast well with such a large animal and it is a tremendous gesture toward social forgiveness.

Be aware that the village could still refuse to come to the feast! Nothing is guaranteed! And if they don’t come, this would signal an unwillingness to reconcile with the family. What happens then? This would be further humiliation resulting as an irremovable stain of shame forever marking this family. The family would be destroyed.

Nevertheless, the father risks all! A Mediterranean audience to this story would be on the edge of their seats!

To the father’s great relief the invitees decide to come! So at this point, the original listeners to the story would have been relieved. It would seem that the story resolves to a happy ending… .

The Lost Elder Son

Everything up to this point in the story (Luke 15:25-32) is going great. The foolish father risked everything, but it paid off, handsomely. The family, hanging over the cliff of doom, seems saved. The father and the younger son are reconciled. The family and the village are reconciled. The village feasts as one and everything goes beautifully. Until the older son arrives.

Why does the older son refuse to enter? This shocking detail constitutes a public humiliation of the father and his entire family. Instead of accepting his brother, thereby honoring father and village, instead of assuming his culturally approved role as chief host at the feast, the older brother insults his father publicly, humiliating him (Luke 15:28-30).

The Lost Contrast

Western readers (including exegetes and theologians) miss that the contrast now in the story is not between the brothers, but rather between the older son and the villagers. Earlier, when both sons took the inheritance (both boys lost to their father, with only one leaving home), yes, the contrast was between the two brothers. Now the villagers have shown up, but the older son refuses to enter.

Why is he enraged? Consider the loss of the liquidated land. Who will be the sole support for the aging father and younger brother, if not the elder? If his younger brother lives at home, imagine the grief that will persist there between the two! But so long as this is contained inside the family and does not spill out publicly, this domestic misery is tolerable. But for all things to be fully reconciled, for the family to be safe and secure, it is essential that both brothers reconcile publicly.

The current Middle Eastern world is the closest thing to a “living laboratory” to ancient life there in the time of Jesus. Today, the elder son would stand at the doorway greeting guests, welcoming them to the feast. Where is he? His absence would communicate volumes to the guests.

The Lost Cause of the Foolish Father

In an unforgettable scene, the father begs his older son to come in (15:28b). Middle Eastern fathers command their sons. They do not entreat them. They never beg. This must be a foolish failed father who cannot control his sons! To beg is shameless!

Then the son insults his father. In his address, the son offers him no respectful title. He refers to himself as a “slave” and not son (15:29). Even though the calf was killed as a peace offering to the villagers—in order to save the family by being reconciled with the village!—the older brother claims otherwise. He claims the old man slaughtered the calf for the younger brother.

Disloyal and Long-Time Lost

The older son disassociates himself from his sibling and entire family by refusing to acknowledge his brother (“this son of yours,” 15:30). By coming to the feast, the villagers acknowledge that the younger son belongs in the family (and, by extension, the family belongs in the village). But the older son is lost—he is outside refusing to come in. He is a disloyal son! And the long-range consequences will be just as devastating for the family and its honor-rating as it was before with the younger son.

Mockingly, the older brother employs deviance labeling to socially destroy his brother forever, making up a claim that he blew the money on prostitutes. The earlier story implies no such thing. It’s vicious, and if it sticks, the younger son will be forced to leave the village to never return. Please understand that no one is safe by this point in this story!

This lost son wishes his father dead. His feet may have always been planted inside the village, but his heart was far away. In effect, this elder son’s heart has always been elsewhere. He, too, wishes his father were already dead. So the contrast is not between the two sons, but between the older son and the villagers. While the villagers entered the feast, the older brother remained an outsider. Everyone is watching.

Could there ever be any doubt that the younger son would show up at the feast? Where does the doubt lie then? It consists on what will happen between the older son and the villagers. Sadly, this essential contrast is completely missed by most exegetes and theologians.

The Foolish Father’s Compassion

Notice how the father acts toward with his elder son. He addresses him as a dear son, and acknowledges his secure place in the family. Likewise, he states the fact that every thing that remains belongs to the older son. By saying “this brother of yours,” the father seeks to repair the older son’s disassociating viciousness in saying, “this brother of yours.”

There is a strong chance that anonymous author we call “Luke” has edited into the story the line that the younger brother “was lost and is found.” This may have been done to fit it with the other two parables earlier in this chapter, that of the Lost Sheep in Luke 15:3-7, and the Lost Coin in 8-10. “Luke” edited these stories together into their present arrangement in his narrative. From whatever source(s) he took them from, it is highly unlikely they existed in the same structure.

Frustrating Ending & More

The story ends abruptly. This frustrates readers. What happened? Consider the public quarrel outside the feast, a quite visible display. Consider what it would communicate to the guests. The villagers would rest assured that this family are untrustworthy. The older son’s actions would confirm this and do irreparable harm to the family and its status in the village.

We are left with a cliffhanger. What did the elder son do?

Going Deeper

We are not done with this Sunday Gospel yet. In the narrative of “Luke,” this story is given with the two other parables of lost things, the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin. Tomorrow we will explore these parables in depth and see how they shape how we are to read the Parable of the Lost Sons.

But what really is the glue that ties this Gospel story together? Tomorrow we will go further, exploring the other two stories and Jesus’ great talent at insults. Then later this week we will wrap around the past three Sunday Gospels to see how all these stories are talking about table fellowship with sinners.